Ukiyo-e: Pictures of the floating world

Ukiyo-e (浮世絵) is a genre of Japanese art that flourished from the 17th to the 19th century. The term “ukiyo-e” translates to “pictures of the floating world”, capturing scenes of urban life, landscapes, and folklore. This art form is renowned for its woodblock prints and paintings, which have significantly influenced the Japanese art scene as well as global art movements, particularly Impressionism. In this post, I’d like to share some of my favorite ukiyo-e prints, as well as a brief overview of the art form’s history and cultural significance.

Video installation from a Yoshitoshi exhibition at the Museum for East Asian Art in Cologne in 2021. Probably based on image 91, Musashi plain moon with a fox (see below).

Video installation from a Yoshitoshi exhibition at the Museum for East Asian Art in Cologne in 2021. Probably based on image 91, Musashi plain moon with a fox (see below).

Historical context

The roots of ukiyo-e can be traced back to the Edo period (1603-1868), a time of peace and stability under the Tokugawa shogunate. During this era, Japan’s social structure transformed, with a burgeoning middle class in urban centers such as Edo (modern-day Tokyo), Osaka, and Kyoto. This new class of merchants and artisans sought entertainment and escapism, leading to the proliferation of kabuki theaters, teahouses, and pleasure districts.

Ukiyo-e emerged as a visual expression of this “floating world” culture, capturing the ephemeral beauty of these urban settings. The earliest ukiyo-e works were monochrome paintings and prints, but advancements in printing techniques soon allowed for multicolored prints.

Most likely one of the oldest surviving ukiyo-e work: The Hikone byōbu (folding screen), dating to c. 1624–1644. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Most likely one of the oldest surviving ukiyo-e work: The Hikone byōbu (folding screen), dating to c. 1624–1644. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Scene from a long narrative scroll kiyomizudera engi emaki retelling the history of a Buddhist monastery, by Tosa Mitsunobu, 1517. The Tosa school is thought to have influenced the development of ukiyo-e. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Scene from a long narrative scroll kiyomizudera engi emaki retelling the history of a Buddhist monastery, by Tosa Mitsunobu, 1517. The Tosa school is thought to have influenced the development of ukiyo-e. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Evolution through the Edo period

The Edo period was marked by a strict social hierarchy and isolationist policies, yet within this context, ukiyo-e thrived as a democratizing force. It became an art form that was accessible to the masses, both in terms of content and affordability.

The earliest ukiyo-e artists, such as Hishikawa Moronobu (1618-1694), were primarily focused on producing illustrations for popular literature. Moronobu is credited with popularizing ukiyo-e through his book illustrations and single-sheet prints.

Portrait of actors, hand-coloured print, by Torii Kiyonobu I, 1714. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Rise of color printing

In the 18th century, advances in printing technology enabled the production of nishiki-e (錦絵, brocade prints), which utilized multiple woodblocks (jap.: iro-ban, 色板; a color block) to create rich, vibrant colors. This innovation allowed artists to produce more complex and appealing images.

Artists such as Suzuki Harunobu (1725-1770) played a significant role in this transformation, producing exquisite prints of bijin-ga (pictures of beautiful women, see below) and everyday scenes that captivated the public.

Perspective Pictures of Places in Japan: Sanjūsangen-dō in Kyoto, by Toyoharu, c. 1772–1781. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Perspective Pictures of Places in Japan: Sanjūsangen-dō in Kyoto, by Toyoharu, c. 1772–1781. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Peak of ukiyo-e

By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, ukiyo-e had reached its zenith, with artists such as Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) creating iconic landscape prints. Hokusai’s Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji and Hiroshige’s The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō are among the most celebrated works of this period, showcasing the natural beauty of Japan’s landscapes.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa (神奈川沖浪裏, Kanagawa-oki Nami Ura), by Hokusai, 1831. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Shōno-juku, from Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, by Hiroshige, c. 1833–34. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Decline and transition

The decline of ukiyo-e began in the late 19th century as Japan underwent rapid modernization and westernization during the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912). The introduction of photography and Western art styles further diminished the demand for traditional ukiyo-e prints. However, ukiyo-e found new audiences abroad, particularly in Europe, where it played a pivotal role in inspiring the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist movements (see below).

Ukiyo-e artists such as Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892) continued to produce innovative and daring prints, exploring darker themes and pushing the boundaries of the art form. However, by the early 20th century, ukiyo-e had largely faded from prominence, replaced by new artistic movements and mediums. The Shin Hanga (“new prints”) movement sought to revive traditional woodblock printing techniques in the early 20th century, but this will be the topic of another post.

Schools of ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e artists were often grouped into schools, each with distinct styles and artistic focuses. I put together a list of the most prominent schools and associated artists and put them into a separate post. Some of the most prominent schools include:

- Tosa School

- The Tosa schoolꜛ was known for its delicate and intricate depictions of classical Japanese themes, often focusing on courtly life and literary subjects. While not exclusively a ukiyo-e school, its techniques and aesthetics influenced early ukiyo-e artists.

- Kanō School

- The Kanō schoolꜛ was a dominant force in Japanese painting from the late 15th century, emphasizing bold brushwork and Chinese-inspired themes. Though more focused on painting, it indirectly influenced ukiyo-e through its emphasis on composition and form.

- Torii School

- The Torii school specialized in kabuki actor portraits (yakusha-e) and theatrical scenes. Founded by Torii Kiyonobu I (1664-1729), the school developed a distinctive style characterized by exaggerated poses and dramatic expressions.

- Katsukawa School

- Founded by Katsukawa Shunshō (1726-1792), the Katsukawa school was renowned for its actor prints and portraits of sumo wrestlers. Shunshō’s innovations in capturing the individuality of his subjects set the stage for later portrait artists.

- Utagawa School

- The Utagawa school was one of the most prolific and influential ukiyo-e schools, producing a wide range of prints, including landscapes, actor portraits, and genre scenes. Artists such as Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Utagawa Kunisada, Utagawa Hiroshige, and Tsukioka Yoshitoshi were key figures in this school.

- Hokusai School

- The Hokusai school, named after the renowned artist Katsushika Hokusai, was known for its landscapes, particularly Hokusai’s iconic series “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji.” Hokusai’s innovative compositions and bold designs set new standards for landscape prints.

Types and themes

Ukiyo-e encompassed a wide range of subjects, reflecting the diverse interests of the Edo-period populace. Some of the most common themes include:

Bijin-ga

Bijin-ga (pictures of beautiful women) was a staple of ukiyo-e, depicting idealized images of women, often courtesans or geisha. These prints celebrated fashion, beauty, and the allure of the “floating world.”

Prominent artists in this genre included Kitagawa Utamaro, known for his intimate and sensuous portrayals of women, capturing their grace and charm.

Bijin-ga example: The Courtesan Someyama of the Matsubaya house, from the series Contest of Beauties in the Gay Quarters, by Eishosai Choki, active from about 1786 to 1808. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Yakusha-e

Yakusha-e (actor prints) focused on kabuki actors, capturing their dramatic poses and expressions. These prints served as both advertisements for theatrical performances and as memorabilia for fans.

Artists like Toshusai Sharaku gained fame for their striking and exaggerated depictions of actors, revealing the theatricality and charisma of kabuki performers.

Yakusha-e example: The Kabuki actors Bando Zenji (on the left, in the role of Benkei) and Sawamura Yodogoro II (on the right, as Yoshitsune), in the play Yoshitsune Senbon Zakura (Yoshitsune of the Thousand Cherry-Trees), by Tōshūsai Sharaku, 1794. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Ōkubi-e

Ōkubi-e (large-head pictures) were a subgenre of ukiyo-e that focused on close-up portraits. These prints emphasized the facial features and expressions of the subject, capturing the intensity and emotion of their performances.

Ōkubi-e example: Kabuki actor Matsumoto Kōshirō IV as Tsurunosuke, by Katsukawa Shunkō I, late 18th c. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Surimono

Surimono were privately commissioned prints that combined poetry with visual art. These prints were often exchanged as gifts among friends and associates, showcasing the sophistication and refinement of the participants. A prominent artists in this genre was Totoya Hokkei.

Fūkei-ga

Fūkei-ga (landscapes) became popular in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, with artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige creating iconic series that celebrated the natural beauty of Japan.

These works often depicted famous landmarks, travel routes, and seasonal scenes, offering viewers a sense of escapism and tranquility.

Fūkei-ga example: Dawn at Futami-ga-ura, by Utagawa Kunisada, c. 1832. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Meoto Iwa (夫婦岩; “husband and wife cliff”), Futami-ga-ura, sub-bay of Ise Bay, Japan (photograph). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Shunga

Shunga (erotic art) was a significant subgenre of ukiyo-e, exploring themes of sexuality and desire. These prints were not considered obscene but rather as a natural and humorous aspect of life.

Artists such as Kitagawa Utamaro and Hokusai produced shunga that were both explicit and artistic, reflecting societal attitudes toward sexuality during the Edo period.

Shunga example: The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, by Hokusai, 1814. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Yūrei-zu

The fascination with the supernatural is evident in ukiyo-e, with many prints depicting ghosts, spirits, and mythological creatures, called yūrei-zu. These works often drew on folklore and legends, capturing the imagination of the audience.

Artists like Tsukioka Yoshitoshi explored these themes, creating haunting and imaginative portrayals of the otherworldly.

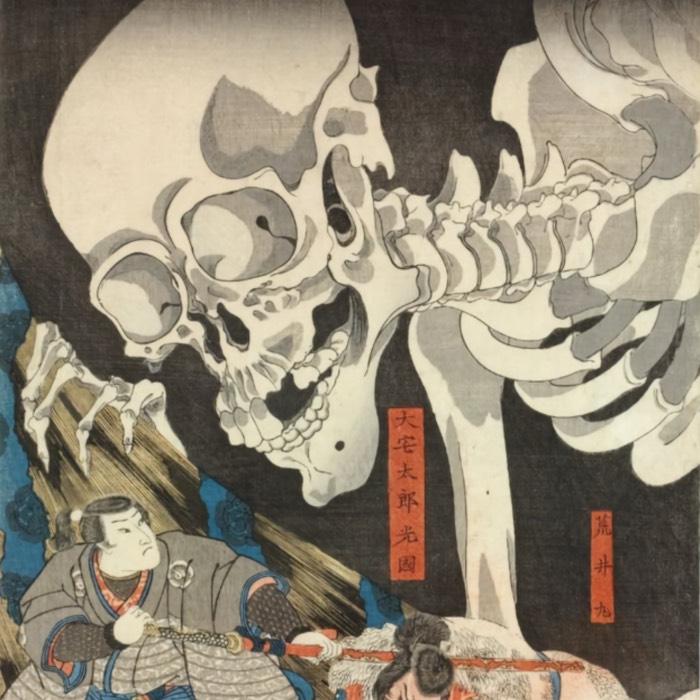

Yūrei-zu example: From the Suikoden series, by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1830. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

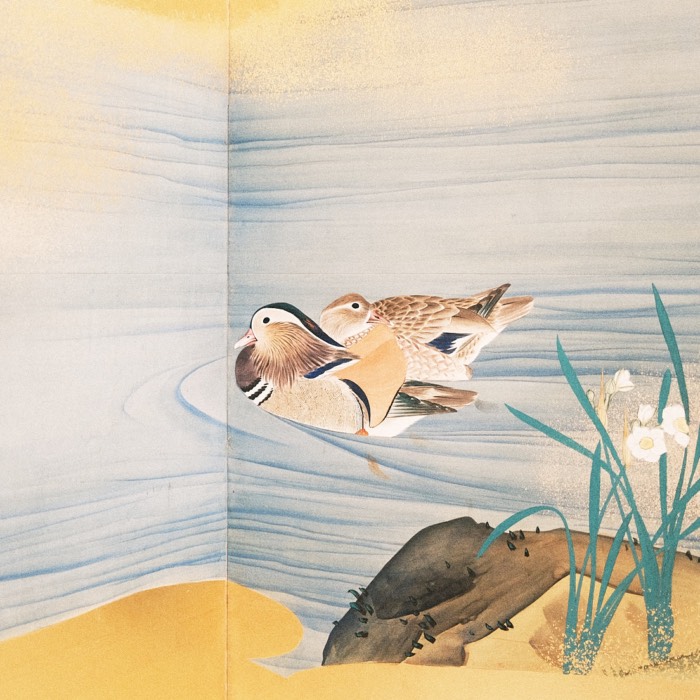

Kachō-ga

Kachō-ga (bird-and-flower prints) celebrated the beauty of nature, focusing on birds, flowers, and other elements of the natural world. These prints often combined realism with artistic interpretation, creating harmonious and visually striking compositions.

Kachō-ga example: Oshidori (mandarin ducks), by Hiroshige, 1830-1838. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Meisho-e

Meisho-e (famous places prints) depicted famous landmarks, travel destinations, and pilgrimage sites across Japan. These prints offered viewers a virtual tour of the country’s most iconic locations, capturing the essence and beauty of each place.

Mitate-e

Mitate-e (parody prints) were humorous and satirical works that parodied historical events, literature, and popular culture. These prints often featured exaggerated characters and playful scenes, providing social commentary and entertainment.

Mitate-e example: Yotaka Goldfish (imitates a goldfish with a night hawk), by Yoshii Ochiai, 1863. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Musha-e

Musha-e (warrior prints) depicted samurai warriors, battles, and historical events. These prints celebrated the martial spirit of Japan’s warrior class, capturing the heroism and valor of legendary figures.

Musha-e example: From the series 47 Ronin, by Ogata Gekko, 1895-1903. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Uchiwa-e

Uchiwa-e (fan prints) were small, circular prints designed to be mounted on fans. These prints often featured seasonal motifs, landscapes, and scenes from daily life, providing a portable and decorative art form.

Uchiwa-e example: View of Fuji from Miho Bay, by Utagawa Toyokuni III, 1830. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Technique

The production of ukiyo-e prints was a sophisticated and collaborative process involving multiple artisans, each specializing in a specific aspect of the creation. This collective effort was essential to achieve the high level of detail and vibrant quality characteristic of ukiyo-e prints. The main stages of production included design, engraving, printing, and publication.

Design

The creation of a ukiyo-e print began with the artist, who was responsible for the initial design. This stage involved several key steps: conceptualization, sketching (kojita-e, 小下絵, a rough sketch), and preparation for carving. The artist conceptualized the scene or subject, often drawing inspiration from contemporary life, literature, kabuki theater, or folklore as explained in the previous section. The artist sketched the design on thin paper using ink and watercolors. These sketches, known as hanshita-e, outlined the main features and details of the composition. The artist’s skill in creating these preliminary drawings was crucial, as they defined the visual and thematic essence of the final print. The hanshita-e was then glued face-down onto a smooth, flat cherry wood block, which served as the master block for carving. This step transferred the design to the wood, allowing engravers to follow the artist’s lines precisely.

Engraving

The engravers or carvers (jap.: horishi, 彫師) played a critical role in transforming the artist’s design into a woodblock ready for printing. This stage required meticulous craftsmanship and precision. The primary block, often called the key block, contained the black outlines of the design (shita-e, 下絵, final preparatory drawing pasted onto the block for printing). Skilled engravers used fine tools to carve away the negative spaces, leaving the raised lines that would later transfer ink to paper. For multicolored prints, separate woodblocks were carved for each color. Each block corresponded to a specific area of the design and required careful alignment with the key block. This process, known as registration, ensured that the different colors would align perfectly during printing. Once the blocks were carved, a proof print was made to check the accuracy and alignment of the blocks. Any necessary adjustments were made before moving to the printing stage.

Japanese woodcutting utensils. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

Japanese woodcutting utensils. Gutenberg Museum, Mainz.

Japanese woodcut print template. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Japanese woodcut print template. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Printing

The printers (jap.: surishi, 摺師) were responsible for transferring the carved designs from the woodblocks to paper, using a complex and layered process to build up the final image. The paper used for ukiyo-e prints was typically handmade washi, known for its strength and ability to hold vibrant colors. The paper was lightly moistened to ensure it would accept the pigments evenly. Natural dyes and pigments were mixed with a binding agent and applied to the woodblocks using brushes. The pigments were chosen for their vividness and durability, contributing to the enduring brilliance of ukiyo-e prints. The moistened paper was carefully placed on the inked woodblock and rubbed with a baren (a flat, disc-like tool) to transfer the pigment from the block to the paper. This process was repeated for each color block, layer by layer, until the full image was created. Each print required multiple passes through the printing process, one for each color. The prints were dried between layers to prevent smudging and ensure crisp, clean lines and vibrant hues.

Japanese woodcut print utensils. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Japanese woodcut print utensils. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

What makes ukiyo-e prints unique is the fact that, while beeing a mass-produced art form, each print was handmade and varied depending on the printer, his technique, the quality of the materials used such as paper and pigments, and the number of prints made from the same block. This resulted in subtle differences between prints, making each one a unique work of art.

Moon over Ships Moored at Tsukuda Island from Eitai Bridge, by Hiroshige, 1857. Left: print variant 1, source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: print variant 2, source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ.

Landscape in Mist (muchū no sansui), by Kunisada, 1832. Left: print variant 1, source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain). – Right: print variant 1, Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Publication

The publishers (jap.: hanmoto, 版元) were integral to the ukiyo-e industry, overseeing the production process and ensuring the prints reached their audience. Publishers financed the production of prints, often commissioning works from popular artists to meet market demands. They decided on the themes and subjects based on consumer preferences and trends. They also marketed the prints, making them available in shops and through itinerant vendors. They played a crucial role in the widespread distribution of ukiyo-e, making the art accessible to a broad audience. Furthermore, they maintained quality control throughout the production process, ensuring that each print met their standards before release.

Significance for Japanese culture

Ukiyo-e holds a special place in Japanese cultural history, capturing the essence of the Edo period’s “floating world.” It offered a window into the lives, fashions, and interests of the time, serving as both art and historical documentation. The genre’s portrayal of beautiful women (bijin-ga), kabuki actors (yakusha-e), landscapes (fūkei-ga), and scenes of daily life (fūzokuga) offered a visual narrative of the Edo period, reflecting the era’s societal dynamics and cultural priorities.

The ukiyo-e prints were mass-produced using woodblock printing techniques, making art accessible to a broader audience. This democratization of art allowed common people to own and appreciate artworks, breaking away from the tradition where art was primarily a privilege of the aristocracy and religious institutions. This widespread distribution of ukiyo-e contributed to its cultural significance and the development of a shared visual language within Japanese society.

Left: Two Lovers Beneath an Umbrella in the Snow, by Harunobu, c. 1767. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Geisha and a servant carrying her shamisen box, by Shigemasa, 1777. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Cooling on Riverside, by Kiyonaga, c. 1785. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Ichikawa Ebizo as Takemura Sadanoshin, by Sharaku, 1794. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Yama-uba with blackened teeth and Kintarō, from Yamanba and Kintaro Sakazuki series, by Kitagawa Utamaro, 18th c. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Amida Falls, from A Tour of Japanese Waterfalls, by Hokusai, 1829-33. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Returning Sails at Tsukuda, from Eight Views of Edo, Hiroshige, early-19th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Mirror of the Japanese Nobility, by Chikanobu, 1887. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Kajikazawa in Kai Province, from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, by Hokusai, forst publication: 1830; this edition: circa 1930. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Sumo wrestling scene, triptych set of three prints, by Kunisada, c. 1851. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Twilight snowfall at Ueno, by Kunisada, c. 1850. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Man on Horseback Crossing a Bridge, from the series The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kiso Kaidō, by Hiroshige, c. 1836-1837. This is View 28 and Station 27 at Nagakubo-shuku, depicting the Wada Bridge across the Yoda River. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Keyamura Rokusuke under the Hikosan Gongen waterfall, by Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Nakamura Fukusuke I as Hayano Kanpei, by Utagawa Kunisada, 1860. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Tenma Bridge in Setsu Province, from Rare Views of Famous Japanese Bridges, by Hokusai. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Influence on Western art

In the late 19th century, ukiyo-e gained international recognition, especially during the wave of Japonisme. This term describes the fascination with and incorporation of Japanese art and design into Western aesthetics, which became particularly prevalent in France and the rest of Europe.

The opening of Japan to international trade in the 1850s, following centuries of isolation under the Tokugawa shogunate’s sakoku policy, allowed for the export of Japanese goods, including ukiyo-e prints. These prints reached Europe and America, where they were displayed in exhibitions and collected by art enthusiasts. The Exposition Universelle held in Paris in 1867ꜛ showcased Japanese art, further fueling interest and appreciation for ukiyo-e among European artists.

Official bird’s-eye view of Exposition Universelle of 1867 in Parisꜛ, by Eugène Ciceri and Philippe Benoist. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

In particular, Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists in the West found inspiration in the stylistic elements of ukiyo-e, such as its use of color, composition, and subject matter. These elements significantly influenced the development of new artistic movements and approaches. Artists like Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt embraced the asymmetrical and cropped compositions found in ukiyo-e, which led to more dynamic and visually engaging scenes. Ukiyo-e prints utilized flat color planes and strong outlines, a technique that intrigued artists such as Vincent van Gogh and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec. This approach led to the simplification of forms and an emphasis on the overall design of the artwork, moving away from realistic representation. Furthermore, the use of diagonals and unusual angles in ukiyo-e inspired Impressionists to experiment with perspective and spatial arrangement, adding movement and depth to their works. And, the vibrant and expressive use of color in ukiyo-e prints influenced Western artists to explore color theory and its emotional impact. Ukiyo-e’s lack of shadowing and modeling prompted artists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir to experiment with light and color as the primary means of conveying mood and atmosphere.

Left: Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi bridge and Atake, by Hiroshige, 1857. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige), by Vincent van Gogh, 1887. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

Left: Bamboo Yards, Kyōbashi Bridge, by Hiroshige, c. 1857–58. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge, by James Abbott McNeill Whistler, an American painter, c. 1872–75. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The influence of ukiyo-e extended beyond the Impressionist movement, leaving a lasting impact on various modern art movements, including Art Nouveau, Post-Impressionism, and Symbolism. The Art Nouveau movement, with its emphasis on natural forms and flowing lines, can be seen as deeply inspired by the organic and decorative qualities of ukiyo-e. Artists and designers adopted Japanese motifs, patterns, and aesthetics, incorporating them into architecture, design, and visual arts. Post-Impressionist artists like Paul Gauguin and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec further explored the expressive and symbolic potential of color and form, drawing inspiration from the flatness and abstraction found in ukiyo-e.

Left: Takashima Ohisa using two mirrors to observe her coiffure, by Kitagawa Utamaro, circa 1795. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) – Right: The Coiffure, drypoint and aquatint, by Mary Cassatt, a French Impressionist, c. 1890–91. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The legacy of ukiyo-e continues to influence contemporary artists and designers worldwide. Its distinctive aesthetics, innovative techniques, and cultural significance have made it a celebrated and enduring art form, appreciated for its beauty, craftsmanship, and historical importance beyond Japan’s borders and beyond its original context and time.

Examples

A few years ago, I was lucky enough to visit a special exhibition on ukiyo-e at the Museum of East Asian Art here in Cologneꜛ. Here are some of my favorite prints that I collected by myself during the visit:

Fulling clothes in Settsu Province, Utagawa HiroshigeHiroshige, 1857, Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Fulling clothes in Settsu Province, Utagawa HiroshigeHiroshige, 1857, Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Shosetsu, Two women in the moonlight, from the series Sanju-roku Kasen (36 examples of female beauties), Mizuno Toshikata (1866-1908), Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Shosetsu, Two women in the moonlight, from the series Sanju-roku Kasen (36 examples of female beauties), Mizuno Toshikata (1866-1908), Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

The Fourth Month, A Lady of the Enkyo Era (1744-1748), Mizuno Toshikata, 1894, Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

The Fourth Month, A Lady of the Enkyo Era (1744-1748), Mizuno Toshikata, 1894, Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Odera Sagami holding sword with impaled head, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: Selection of 100 Warriors (Kaidai hyaku sensō, 1868-1869), Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Odera Sagami holding sword with impaled head, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: Selection of 100 Warriors (Kaidai hyaku sensō, 1868-1869), Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Inada Kyūzō Shinsuke: woman suspended from rope, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi and Utagawa Yoshiiku, from the series: Twenty-Eight Famous Murders with Verse (1860ies). Muzan-e (無残絵), also known as ‘Bloody Prints’, refers to Japanese woodcut prints of violent nature published in the late Edo and Meiji periods. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Inada Kyūzō Shinsuke: woman suspended from rope, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi and Utagawa Yoshiiku, from the series: Twenty-Eight Famous Murders with Verse (1860ies). Muzan-e (無残絵), also known as ‘Bloody Prints’, refers to Japanese woodcut prints of violent nature published in the late Edo and Meiji periods. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Inabe Mountain moon, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi, 1885-1892). Toyotomi Hideyoshi scales a cliff by moonlight. He is seeking an unguarded route into the Saito stronghold of Gifu castle. This castle was located in a strategically important location in Mino province. In 1564, the well-guarded castle had effectively stopped the forward progress of Oda Nobunaga’s military campaign. Hideyoshi carries a water gourd upon his back which he will later raise on a pole once inside the castle, signalling his troops. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Inabe Mountain moon, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi, 1885-1892). Toyotomi Hideyoshi scales a cliff by moonlight. He is seeking an unguarded route into the Saito stronghold of Gifu castle. This castle was located in a strategically important location in Mino province. In 1564, the well-guarded castle had effectively stopped the forward progress of Oda Nobunaga’s military campaign. Hideyoshi carries a water gourd upon his back which he will later raise on a pole once inside the castle, signalling his troops. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

The moon of Ogurusu in Yamashiro, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi, 1885-1892). In 1582, Akechi Mitsuhide forced Oda Nobunaga to commit seppaku. His forces were then promptly routed by Hideyoshi at the Battle of Yamazaki (Tennozan). Mitsuhide fled, but was killed by a peasant militia near the village of Ogurusu. In this print, Mitsushide is horseback, under the moon. A peasant watches, planning the ambush. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

The moon of Ogurusu in Yamashiro, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi, 1885-1892). In 1582, Akechi Mitsuhide forced Oda Nobunaga to commit seppaku. His forces were then promptly routed by Hideyoshi at the Battle of Yamazaki (Tennozan). Mitsuhide fled, but was killed by a peasant militia near the village of Ogurusu. In this print, Mitsushide is horseback, under the moon. A peasant watches, planning the ambush. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Faith in the third-day moon, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi, 1885-1892). A 16th century warrior, Yamanaka Shikanosuke Yukimori (1545-1578) is said to have taken his first head at age 13. He served the lord of Izumo province, and fought many battles against the Mōri, an invading clan. Among Yukimori’s many exploits was a single combat against a Mōri champion on a small island, surrounded by forces from both sides. He believed in the luck of the ‘mikazuki’ or third-day moon, and he wears this moon upon his helmet. Yukimori died at the age of 34. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Faith in the third-day moon, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi, 1885-1892). A 16th century warrior, Yamanaka Shikanosuke Yukimori (1545-1578) is said to have taken his first head at age 13. He served the lord of Izumo province, and fought many battles against the Mōri, an invading clan. Among Yukimori’s many exploits was a single combat against a Mōri champion on a small island, surrounded by forces from both sides. He believed in the luck of the ‘mikazuki’ or third-day moon, and he wears this moon upon his helmet. Yukimori died at the age of 34. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Mountain moon after rain, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi, 1885-1892). The Soga brothers, Gorō Tokimune and Jūrō Sukenari were orphaned at a young age when their father was killed by Kudō Suketsune. The story of their revenge is well known in Japanese literature, and featured in many prints by various artists. In 1193, they crept into Suketsune’s hunting camp and successfully killed him. Jurō was killed in the subsequent fighting, Gorō was captured and brought before the shogun and was decapitated. Here Gorō pauses in his infiltration of Suketsune’s camp to watch a cuckoo fly across the moonlight.

Mountain moon after rain, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi, 1885-1892). The Soga brothers, Gorō Tokimune and Jūrō Sukenari were orphaned at a young age when their father was killed by Kudō Suketsune. The story of their revenge is well known in Japanese literature, and featured in many prints by various artists. In 1193, they crept into Suketsune’s hunting camp and successfully killed him. Jurō was killed in the subsequent fighting, Gorō was captured and brought before the shogun and was decapitated. Here Gorō pauses in his infiltration of Suketsune’s camp to watch a cuckoo fly across the moonlight.

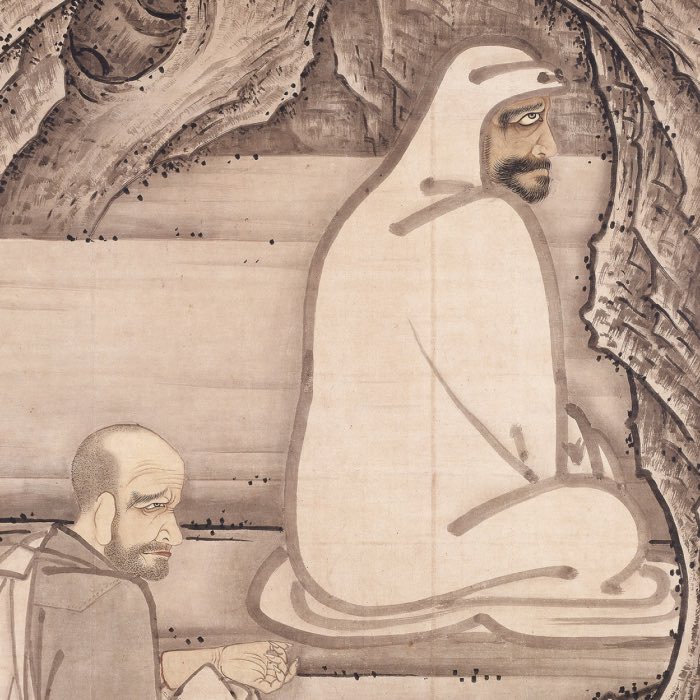

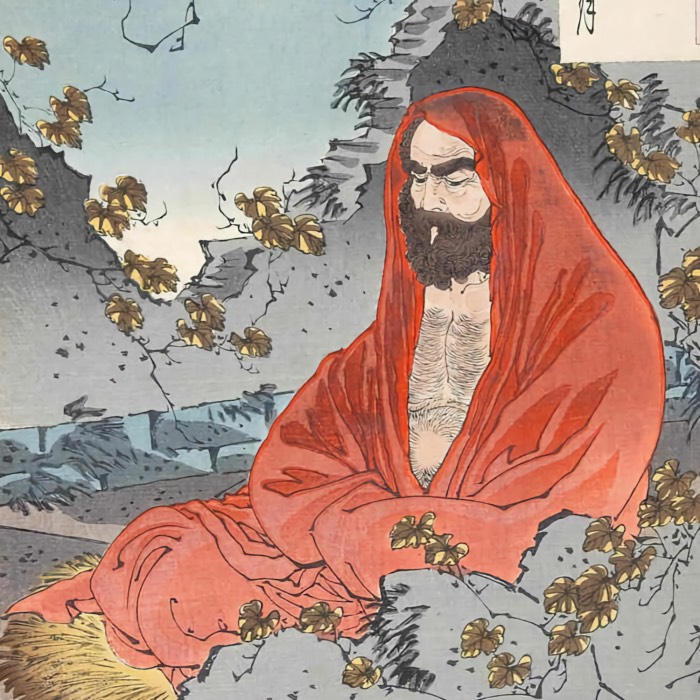

The moon through a crumbling window, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi, 1885-1892). Chán- or Zen-Buddhismus was founded in China in the early 5th century by Bodhidharma, a former Indian prince. Bodhidharma, or Daruma in Japanese, taught that enlightenment was obtained through experiential realization via meditation. Daruma was said to have meditated for nine years facing a wall, which gradually disintegrated. This image is depicted in Yoshitoshi’s print. Zen-Buddhism was established as a separate school in Japan in the 12th century. Many stories have been told about Daruma, emphasizing his dedication, determination, and persistence. Japanese Daruma dolls are used to make wishes, or to commit to a specific goal. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

The moon through a crumbling window, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi, 1885-1892). Chán- or Zen-Buddhismus was founded in China in the early 5th century by Bodhidharma, a former Indian prince. Bodhidharma, or Daruma in Japanese, taught that enlightenment was obtained through experiential realization via meditation. Daruma was said to have meditated for nine years facing a wall, which gradually disintegrated. This image is depicted in Yoshitoshi’s print. Zen-Buddhism was established as a separate school in Japan in the 12th century. Many stories have been told about Daruma, emphasizing his dedication, determination, and persistence. Japanese Daruma dolls are used to make wishes, or to commit to a specific goal. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Gidayū writes his death poem by moonlight, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi, 1885-1892). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Gidayū writes his death poem by moonlight, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi, 1885-1892). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Mount Ji Ming moon, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi, 1885-1892). The Chinese state of Han was conquered by the Qin in 230 BC. The short-lived Qin dynasty ended with the death of the first emperor in 206 BC. A Han leader, Liu Bang eventually became victorious in the following civil war, establishing the Han dynasty (202 BC - 220 CE). Liu Bang defeated his chief rival, Xiang Yu, at the Battle of Gaixia in 202 BC. In this print, the chief Han strategist, Zi Fang (Zhang Liang, d. 189) observes an enemy encampment from the lines of Liu Bang. He was said to have played a flute, the sweet sound bringing the enemy to tears. After the establishment of the Han dynasty, Zi Fang left governement service to attend to spiritual pursuits. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Mount Ji Ming moon, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi, 1885-1892). The Chinese state of Han was conquered by the Qin in 230 BC. The short-lived Qin dynasty ended with the death of the first emperor in 206 BC. A Han leader, Liu Bang eventually became victorious in the following civil war, establishing the Han dynasty (202 BC - 220 CE). Liu Bang defeated his chief rival, Xiang Yu, at the Battle of Gaixia in 202 BC. In this print, the chief Han strategist, Zi Fang (Zhang Liang, d. 189) observes an enemy encampment from the lines of Liu Bang. He was said to have played a flute, the sweet sound bringing the enemy to tears. After the establishment of the Han dynasty, Zi Fang left governement service to attend to spiritual pursuits. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Yasumasa playing the flute by moonlight, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1883. The Heian poet Yasumasa playing the flute by moonlight, subduing the bandit Yasusuke with his Music. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Yasumasa playing the flute by moonlight, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1883. The Heian poet Yasumasa playing the flute by moonlight, subduing the bandit Yasusuke with his Music. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Left: Full moon on the Tatami mats, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi, 1885-1892). It is early autumn, and a courtesan gazes at the shadow of of pine branches thrown by the moon. The print contains a poem by the haiku artist Tarakai Kikaku (1661-1707) who was associated in some respects with the Yoshiwara district. Right: The Village of the Shi Clan. Shi Jin was a bandit hero featured in the Chinese novel Shui hu Zhaun, which was translated into the Japanese Suikoden. He is heavily tattooed, and was nicknamed ‘Kumonryū’ or ‘Nine-dragoned’ for his many dragon tattoos. Here, Shi Jin relaxes in his village before fleeing from arrest. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Left: Full moon on the Tatami mats, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series: One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (Tsuki hyakushi, 1885-1892). It is early autumn, and a courtesan gazes at the shadow of of pine branches thrown by the moon. The print contains a poem by the haiku artist Tarakai Kikaku (1661-1707) who was associated in some respects with the Yoshiwara district. Right: The Village of the Shi Clan. Shi Jin was a bandit hero featured in the Chinese novel Shui hu Zhaun, which was translated into the Japanese Suikoden. He is heavily tattooed, and was nicknamed ‘Kumonryū’ or ‘Nine-dragoned’ for his many dragon tattoos. Here, Shi Jin relaxes in his village before fleeing from arrest. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

The ghost of the maid who was killed and thrown in the well afer she broke one of her lord’s plates rising up, Katsushika Hokusai, from the series: 100 Ghost Stories (Hyaku monogatari), 1831. After the maid Okiku had accidentally broken one of a set of elegant Korean plates, her infuriated master bound her and threw her down a well, where she died in body but not spirit. In 1795, wells around Japan became infested with a species of worm covered in thin threads, which people believed to be a reincarnation of Okiku; the threads being the remnants of the fabric used to bind her. They named it ‘Okiku mushi’ (the Okiku bug). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

The ghost of the maid who was killed and thrown in the well afer she broke one of her lord’s plates rising up, Katsushika Hokusai, from the series: 100 Ghost Stories (Hyaku monogatari), 1831. After the maid Okiku had accidentally broken one of a set of elegant Korean plates, her infuriated master bound her and threw her down a well, where she died in body but not spirit. In 1795, wells around Japan became infested with a species of worm covered in thin threads, which people believed to be a reincarnation of Okiku; the threads being the remnants of the fabric used to bind her. They named it ‘Okiku mushi’ (the Okiku bug). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Oiwa, Katsushika Hokusai, from the series: 100 Ghost Stories (Hyaku monogatari), 1831. The young Oume falls in love with the married Samurai Tamiya Iemon, and her friends try to get his wife Oiwa out of the picture with a gift of poisonous face cream. When Iemon abandons his newly disfigured wife, it sends her mad with grief. In her hysteria she runs and trips onto a sword, cursing Iemon with her dying breath — and then adopting various forms to haunt him, including a paper lantern (Chōchin-obake). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Oiwa, Katsushika Hokusai, from the series: 100 Ghost Stories (Hyaku monogatari), 1831. The young Oume falls in love with the married Samurai Tamiya Iemon, and her friends try to get his wife Oiwa out of the picture with a gift of poisonous face cream. When Iemon abandons his newly disfigured wife, it sends her mad with grief. In her hysteria she runs and trips onto a sword, cursing Iemon with her dying breath — and then adopting various forms to haunt him, including a paper lantern (Chōchin-obake). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

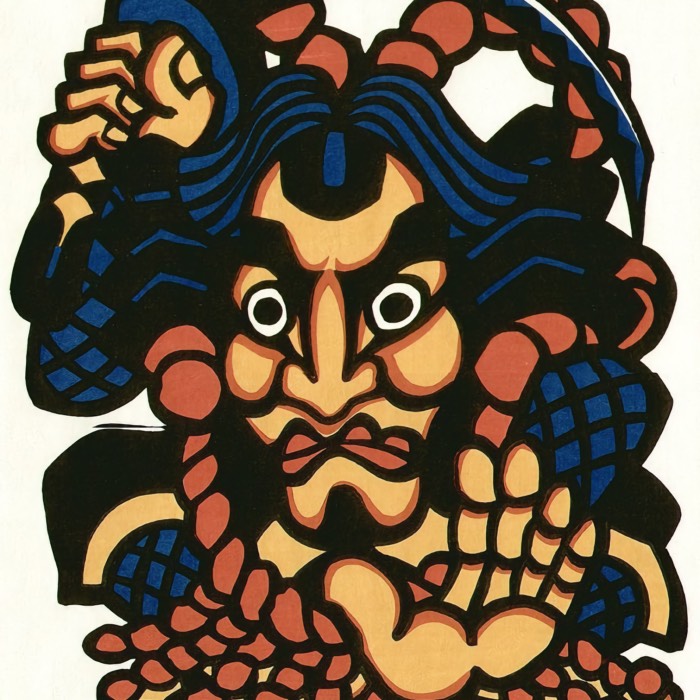

Kabuki actors and the spirit of the old cat in the play Onoe Juity Dayhanasi, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1847, Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Kabuki actors and the spirit of the old cat in the play Onoe Juity Dayhanasi, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1847, Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Onoe Kikugoro V as the witch of Adachigahara, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1890, Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Onoe Kikugoro V as the witch of Adachigahara, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1890, Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

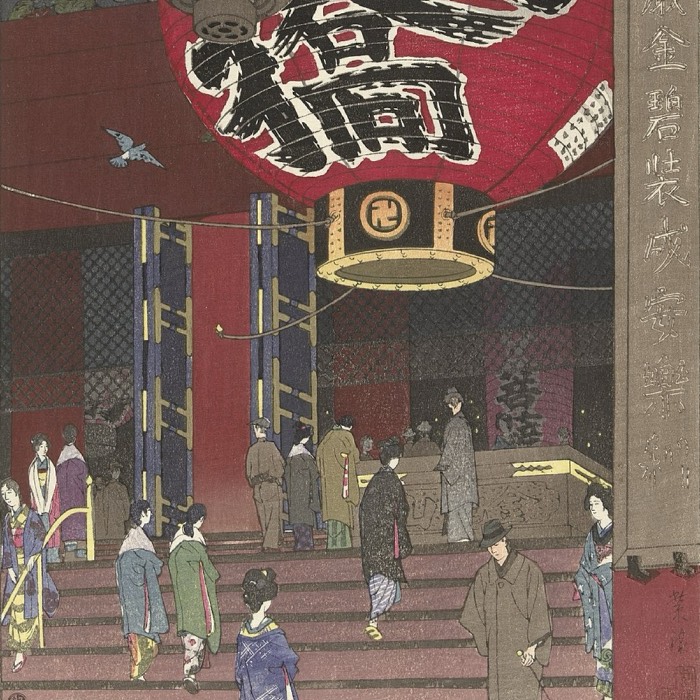

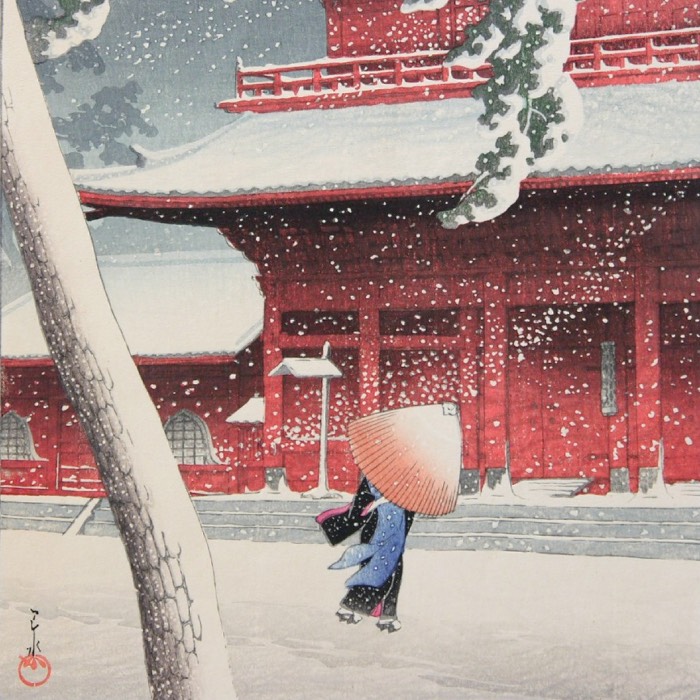

View of Ochanomizu (Ochanomizu no zu), Utagawa Hiroshige, 1832-1839, from the series Famous Places in the Eastern Capital (Toto meisho), Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

View of Ochanomizu (Ochanomizu no zu), Utagawa Hiroshige, 1832-1839, from the series Famous Places in the Eastern Capital (Toto meisho), Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

45th station: Shōno (Travellers surprised by sudden rain), 庄野, Shōno, Utagawa Horishige, 1833-1834, from the series: The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō (東海道五十三次, Tōkaidō Gojūsan-tsugi), Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

45th station: Shōno (Travellers surprised by sudden rain), 庄野, Shōno, Utagawa Horishige, 1833-1834, from the series: The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō (東海道五十三次, Tōkaidō Gojūsan-tsugi), Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Conclusion

What fascinates me about ukiyo-e is its ability to provide a vivid glimpse into the cultural and social life of a bygone era. These prints offer a visual narrative of Japan during the Edo period, capturing the elegance and story of its people and the beauty of landscapes. As an art form, it democratized art ownership in Japan by making prints accessible to the masses. Beyond its historical significance, ukiyo-e has profoundly impacted Western art, particularly during the 19th-century wave of Japonisme. Artists like Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet, and Edgar Degas were inspired by ukiyo-e’s innovative use of color, composition, and perspective, incorporating these elements into their own work and leading to the development of new artistic styles.

Today, ukiyo-e is celebrated for its historical and artistic value, appreciated for its beauty and craftsmanship. Museums around the world, including the Ukiyo-e Ota Memorial Museum of Artꜛ in Tōkyō, the British Museumꜛ in London, and the Nihon no hangaꜛ in Amsterdam house extensive collections of ukiyo-e prints. I think, this art form stands as a symbol of global cultural exchange, illustrating how art transcends borders and time, enriching our understanding of visual expression across cultures and centuries.

References and further reading

- Woldemar von Seidlitz, Dora Amsden, Ukiyo-e, 2016, Parkstone International, ISBN: 9781785257391

- Amy Reigle Newland, The Hotei encyclopedia of Japanese woodblock prints, 2005, Hotei Publishing, ISBN: 9789074822657

- Rebecca Salter, Japanese Woodblock Printing, 2002, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN: 9780824825539

- Richard Lane, Masters of the Japanese print, their world and their work, 2021, Hassell Street Press, ISBN: 9781015300231

- Andreas Marks, Japanese Woodblock Prints - Artists, Publishers And Masterworks: 1680 - 1900, 2010, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN: 9784805310557

- Wikipedia articles on Ukiyo-eꜛ, Japonismeꜛ, and List of Ukiyo-e termsꜛ

- ukiyo-e.orgꜛ

- artelino.comꜛ

- Ukiyo-e Ota Memorial Museum of Artꜛ

- British Museumꜛ

- Nihon no hangaꜛ

comments