Byōbu – The art of Japanese folding screens

The tradition of kakemono and emakimono is closely related to other forms of Japanese narrative art, such as byōbu (屏風) and fusuma (襖). Byōbu are folding screens that feature painted scenes, often with narrative elements, while fusuma are sliding doors that can be decorated with paintings or calligraphy. Together, these art forms create a rich visual narrative expression in Japanese culture, reflecting the interconnectedness of art, literature, and daily life.

Example of a six-panel byōbu from the 17th century. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: Copyrighted free use)

Pair of screens with a leopard, tiger and dragon by Kanō Sanraku, 17th century, each 1.78 m × 3.56 m. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: Copyrighted free use)

The history of byōbu

Byōbu (屏風), traditional Japanese folding screens, are believed to have originated in China during the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 CE) and were likely introduced to Japan in the 7th or 8th century, during the Nara period (710–794). The earliest known byōbu made in Japan is the Torige ritsujo no byōbu (鳥毛立女屏風) from the 8th century, preserved in the Shōsōin treasure house.

Initially, Nara period byōbu retained their original form as single, freestanding panels with legs. By the 8th century, multi-paneled byōbu emerged, serving as essential furniture items at the imperial court, particularly during significant ceremonies. The six-paneled byōbu were most common during this time, covered with silk and connected by leather or silk cords. Each panel’s painting was framed with silk brocade and bordered with a wooden frame.

During the Heian period (794–1185), especially in the 9th century, byōbu became indispensable furniture in the residences of Daimyō, Buddhist temples, and shrines. The introduction of zenigata (銭形), coin-shaped metal hinges, replaced silk cords to connect the panels. As Japanese culture began to develop independently from continental Asian influences after the Heian period, the design of byōbu evolved, becoming an integral part of the architectural style known as shinden-zukuri.

In the Muromachi period (1392–1568), folding screens gained popularity in various settings, including homes, dojos, and shops. Two-paneled byōbu became standard, with overlapping paper hinges replacing zenigata, making them more portable, easier to fold, and sturdier at the joints. This technique allowed for uninterrupted illustrations across panels, leading artists to create magnificent, often monochromatic, natural scenes and landscapes of famous Japanese sites.

Despite the stability of paper hinges, the panel infrastructure needed to remain as lightweight as possible. Softwood lattices were constructed using special bamboo nails, allowing the lattice to be planed straight and square along its edges, matching the size of other byōbu panels. The lattices were covered with one or more layers of paper, stretched tightly like a drumhead to provide a flat and robust surface for paintings. The resulting structure was lightweight and durable, yet delicate. After attaching the paintings and brocade, a lacquered wooden frame (usually black or dark red) was added to protect the byōbu’s outer perimeter. Elaborate metal fittings (strips, right angles, and rivets) were applied to the frame to protect the lacquer.

During the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1568–1600) and the early Edo period (1600–1868), byōbu’s popularity grew significantly, driven by the merchant classes’ increased interest and investment in arts and crafts. byōbu adorned samurai residences, symbolizing high status, wealth, and power. This led to radical changes in byōbu craftsmanship, such as the use of gold leaf backgrounds (kinpaku, 金箔) and vibrant paintings depicting nature and everyday life scenes, a style developed by the Kanō school.

Today, byōbu are often machine-made; however, handcrafted byōbu are still available, primarily produced by families dedicated to preserving these traditional crafts.

Example of a modern byōbu: “A Thousand Cranes Source” by Kayama Matazō. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Types of byōbu

Byōbu can be classified into several categories based on their size, number of panels, and painting style.

Classification by number of panels:

- Tsuitate (衝立): These single-panel screens, originally the only type with legs, represent the earliest form of byōbu. Today, they are commonly found in shops, event venues, and restaurants.

- Nikyoku Byōbu (二曲屏風) or Nimaiori Byōbu (二枚折屏風): These are two-panel screens first introduced in the mid-Muromachi period. They play a significant role in Japanese tea ceremony rooms, where they are placed at the edge of the host’s mat to separate the host’s area from that of the guests. Typically measuring about 60 cm high and 85 cm wide, these screens are also known as Furosaki Byōbu (風炉先屏風) within the context of tea ceremonies.

- Yonkyoku Byōbu (四曲屏風): Four-panel screens that were prominently displayed in the corridors during the Kamakura and Muromachi periods. They were later used in Seppuku ceremonies (Japanese ritual suicide) and in the waiting rooms of tea houses during the late Edo period.

- Rokkyoku Byōbu (六曲屏風) or Rokumaiori Byōbu (六枚折屏風): Comprising six panels, this is the most popular format, typically measuring about 1.5 m in height and 3.7 m in width.

- Jūkyoku Byōbu (十曲屏風): Featuring ten panels, this relatively modern format is used as a backdrop in large spaces such as hotel lobbies and conference rooms.

Classification by uses and themes:

- Ga no Byōbu (賀の屏風, literally: Longevity Screens): Since the Heian period, these screens have been used to celebrate longevity, featuring Waka poems and often adorned with paintings of birds and flowers representing the four seasons.

- Shiro-e Byōbu (白絵屏風) or Shirae Byōbu: These screens are painted with ink or mica on a white silk surface and were commonly used during the Edo period for wedding ceremonies. They were also employed in rooms where births took place, hence the name Ubuya Byōbu (産所屏風, Birthplace Screen). Their designs typically include cranes, turtles with pine trees and bamboo, and the auspicious Fenghuang (Chinese phoenix).

- Makura Byōbu (枕屏風, literally: Pillow Screen): Measuring about 50 cm high and often made with two or four panels, these screens are typically used in bedrooms to store clothes or other items and to create a sense of privacy.

- Koshi Byōbu (腰屏風): Slightly taller than Makura Byōbu, these screens were used during the tumultuous Sengoku period, positioned behind the host to reassure guests that no one was hiding behind them.

Examples

Here are some shots of the most remarkable examples of byōbu that I was able to collect during my recent visits to various museums and exhibitions:

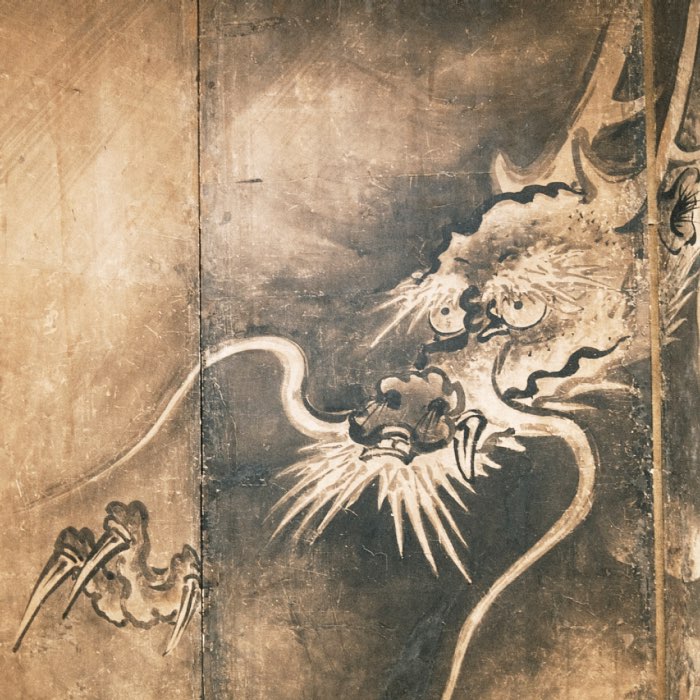

Dragon and Tiger, attributed to Tosa Mitsutsugu (active ca. 1624-1644), pair of six-fold screens (byōbu), ink on paper Japan, first half 17th century. Tiger and dragon symbolize the duality of heaven and earth. In China, their cosmological meaning referred to the eastern and western directions, spring and fall, rain and wind, and the elements of wood and metal. In Japan, the dragon and tiger are associated as a pair with two hanging scrolls dated 1269 by the Chán monk painter Muqi in the possession of Daitoku-ji in Kyoto. Here, the placement of the dragon on the right and the tiger on the far left creates an exciting space in between. Diagonally swept brushstrokes suggest rain in the dragon depiction, while the waving bamboo leaves in the tiger picture suggest wind. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Dragon and Tiger, attributed to Tosa Mitsutsugu (active ca. 1624-1644), pair of six-fold screens (byōbu), ink on paper Japan, first half 17th century. Tiger and dragon symbolize the duality of heaven and earth. In China, their cosmological meaning referred to the eastern and western directions, spring and fall, rain and wind, and the elements of wood and metal. In Japan, the dragon and tiger are associated as a pair with two hanging scrolls dated 1269 by the Chán monk painter Muqi in the possession of Daitoku-ji in Kyoto. Here, the placement of the dragon on the right and the tiger on the far left creates an exciting space in between. Diagonally swept brushstrokes suggest rain in the dragon depiction, while the waving bamboo leaves in the tiger picture suggest wind. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Byōbu showing a festival scene in Kyoto. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Byōbu showing a festival scene in Kyoto. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Birds and flowers in the Maruyama Yakushin Bird and Flower Gallery (円山厄震 花鳥冈屏風), Japan, Edo period, first half 19th c., pair of six-panel folding screens (byōbu), ink and colors on gold leaf, paper. Seen in an exhibition at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin

Birds and flowers in the Maruyama Yakushin Bird and Flower Gallery (円山厄震 花鳥冈屏風), Japan, Edo period, first half 19th c., pair of six-panel folding screens (byōbu), ink and colors on gold leaf, paper. Seen in an exhibition at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin

Conclusion

Like kakemono and emakimono, byōbu are an essential part of Japanese art history, reflecting the country’s cultural and artistic development over centuries. The folding screens’ versatility and adaptability to various settings and themes have made them a popular choice for interior decoration, religious ceremonies, and public events. Their intricate designs and meticulous craftsmanship continue to inspire contemporary artists and designers, preserving the tradition of Japanese narrative art for future generations. At the same time, the byōbu serve as a narrative window into Japan’s rich cultural heritage, offering insights into the country’s history, aesthetics, and spiritual beliefs.

If you know of any other upcoming exhibitions or museums that feature remarkable examples of byōbu, please feel free to share them in the comments below.

References and further reading

- Harald Olbrich, Gerhard Strauß, Lexikon der Kunst - A - Cim, 1996, dtv Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG, ISBN: 9783423059060

- Gabriele Fahr-Becker, Ostasiatische Kunst, 2011, Ullmann, ISBN: 9783833160998

- Danielle Elisseeff, Vadime Elisseeff, Art Of Japan, 1985, ABRAMS, ISBN: 9780810906426

- Masako Watanabe, Storytelling In Japanese Art, 2011, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, ISBN: 9780300175905

- Adele Schlombs, Sybille Girmond, Meisterwerke aus China, Korea und Japan, 1995, Prestel, ISBN: 9783791314945

- Matazō Kayama, Lawrence Smith, Kayama Matazō - New Triumphs for Old Traditions, 1996, Verlag n/a, ISBN: 9784532159993

- English Wikipedia article about byōbuꜛ

- German Wikipedia article about byōbuꜛ

comments