Emakimono: The art of Japanese handscrolls

Emakimono (絵巻物; short: emaki, 絵巻), or Japanese handscrolls, are a captivating form of narrative art that emerged during the Heian period (794-1185 CE) in Japan. These exquisite scrolls combine text and pictures to tell stories, document courtly life, or illustrate poetic themes. The format allows for sequential viewing, where the story unfolds as the scroll is gradually unrolled from right to left, offering a unique and intimate artistic experience. In this post, we explore the history, techniques, and cultural significance of emakimono in Japanese art and literature.

Portrait of Wu Yihan Portrait of Wu Yihan, Gu Jianlong (1606 - after 1689), horizontal scroll, ink and colors on silk, China, Qing dynasty, Kangxi period, dated 1689. Wu Yihan is sitting under a pine tree in the manner of a Daoist sage, playing a zither and contemplating a waterfall. According to the inscription, he visited the 84-year-old painter Gu Jianlong on a summer’s day, chatted with him until the evening and then asked him to paint this portrait. Seven other scholars have written postscripts on the scroll. Part of the exhibition 50 Years – 50 Treasures exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne.

Portrait of Wu Yihan Portrait of Wu Yihan, Gu Jianlong (1606 - after 1689), horizontal scroll, ink and colors on silk, China, Qing dynasty, Kangxi period, dated 1689. Wu Yihan is sitting under a pine tree in the manner of a Daoist sage, playing a zither and contemplating a waterfall. According to the inscription, he visited the 84-year-old painter Gu Jianlong on a summer’s day, chatted with him until the evening and then asked him to paint this portrait. Seven other scholars have written postscripts on the scroll. Part of the exhibition 50 Years – 50 Treasures exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne.

Chinese origins and Japanese tradition

The tradition of emakimono has its roots in China, where handscrolls were used to document historical events, religious teachings, and literary works. While the first handscrolls from the Spring and Autumn period (770–481 BC) were made of bamboo or wood that were bound together, the later scrolls were made of silk or paper (since the Eastern Han period, 25–220). These scrolls were unrolled horizontally, with the viewer reading the text from right to left as the images were revealed, and the often featured illustrations alongside text.

When the practice of handscroll painting reached Japan through the spread of Buddhism, it underwent a transformation that reflected the unique cultural and artistic sensibilities of the Japanese people. The Japanese emakimono retained the horizontal format but introduced new themes, styles, and techniques that were distinct from their Chinese predecessors. Unlike Japanese hanging scrolls (kakemono, 掛け物), which are meant for display, emakimono are interactive objects, meant to be held and viewed in private, creating a personal engagement with the artwork.

Famous examples of emakimono include the “Genji Monogatari Emaki”, a visual adaptation of Murasaki Shikibu’s literary masterpiece “The Tale of Genji”, and the “Choju Jinbutsu Giga”, often considered the world’s first manga because of its humorous and satirical depictions of animals in monastic life.

Here are some of my favorite examples of emakimono that I have seen in various museums in the recent past:

The War of the twelve zodiac Animals, Unidentified painter, handscrolls (emakimono), ink, pigment and gold on paper Japan, 17th-18th century. The scroll is a copy of earlier versions created from the 15th century on, as a form of political satire. It depicts the poetry contest of the twelve zodiac animals who ore the messengers of the Twelve Divine Generals (jūni shinshō) in the retinue of the Medicine Buddha. The deer and the racoon claim that they are also ‘immortal poets’ (kasen). Here, scene 4 is shown: The racoon retreats. He gathers fellow animals not included in the elite group of twelve animals and forms an army. They drink, eat and scheme a night attack. The Cologne scroll ends at this point, but the narrative continues until the racoon finally realizes his conceit, goes on a pilgrimage in search of enlightenment and lives peacefully as a monk. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

The War of the twelve zodiac Animals, Unidentified painter, handscrolls (emakimono), ink, pigment and gold on paper Japan, 17th-18th century. The scroll is a copy of earlier versions created from the 15th century on, as a form of political satire. It depicts the poetry contest of the twelve zodiac animals who ore the messengers of the Twelve Divine Generals (jūni shinshō) in the retinue of the Medicine Buddha. The deer and the racoon claim that they are also ‘immortal poets’ (kasen). Here, scene 4 is shown: The racoon retreats. He gathers fellow animals not included in the elite group of twelve animals and forms an army. They drink, eat and scheme a night attack. The Cologne scroll ends at this point, but the narrative continues until the racoon finally realizes his conceit, goes on a pilgrimage in search of enlightenment and lives peacefully as a monk. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

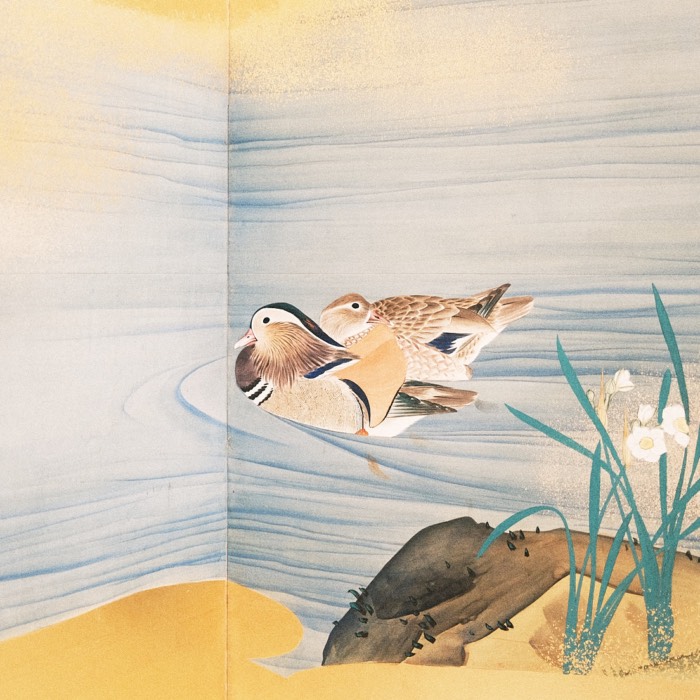

Scene from: Paintings by 27 Pupils of Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795), handscroll (emakimono), ink and light color on paper between 1789 and 1801. The handscroll comprises 48 signed and sealed sketches of figures, land-scapes, plants and animals rendered by pupils and successors of Maruyama Okyo. Possibly the scroll was not a collector’s item, but served pointers of the Maruyama-Shijo school as a pattern book. The Maruyama-Shijo school, a significant force in Japanese art during the Edo and Meiji periods, was renowned for its distinctive style. This school skillfully blended traditional Japanese artistic techniques with Western elements of naturalism and realism, creating a unique and influential aesthetic.

Scene from: Paintings by 27 Pupils of Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795), handscroll (emakimono), ink and light color on paper between 1789 and 1801. The handscroll comprises 48 signed and sealed sketches of figures, land-scapes, plants and animals rendered by pupils and successors of Maruyama Okyo. Possibly the scroll was not a collector’s item, but served pointers of the Maruyama-Shijo school as a pattern book. The Maruyama-Shijo school, a significant force in Japanese art during the Edo and Meiji periods, was renowned for its distinctive style. This school skillfully blended traditional Japanese artistic techniques with Western elements of naturalism and realism, creating a unique and influential aesthetic.

Painting by Kameoka Kirei (1770-1835). Another scene from: Paintings by 27 Pupils of Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795). Handscroll, ink and light color on paper between 1789 and 1801.

Painting by Kameoka Kirei (1770-1835). Another scene from: Paintings by 27 Pupils of Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795). Handscroll, ink and light color on paper between 1789 and 1801.

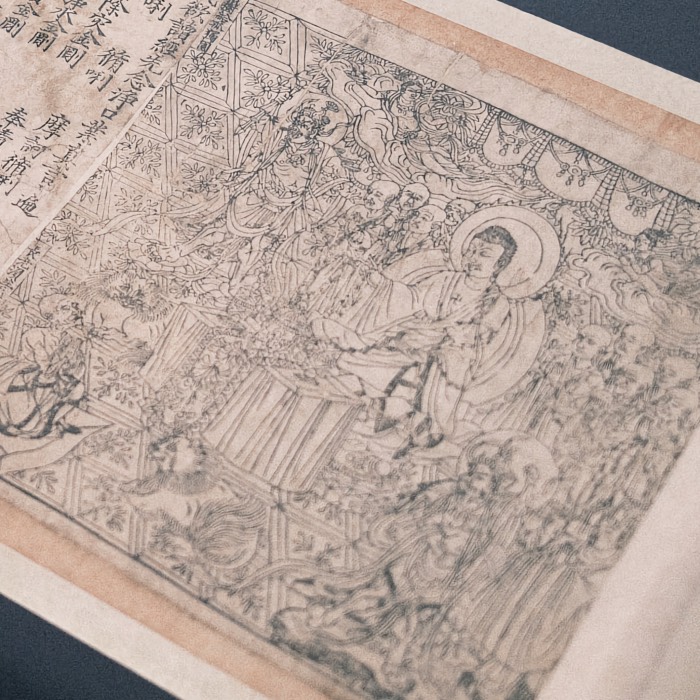

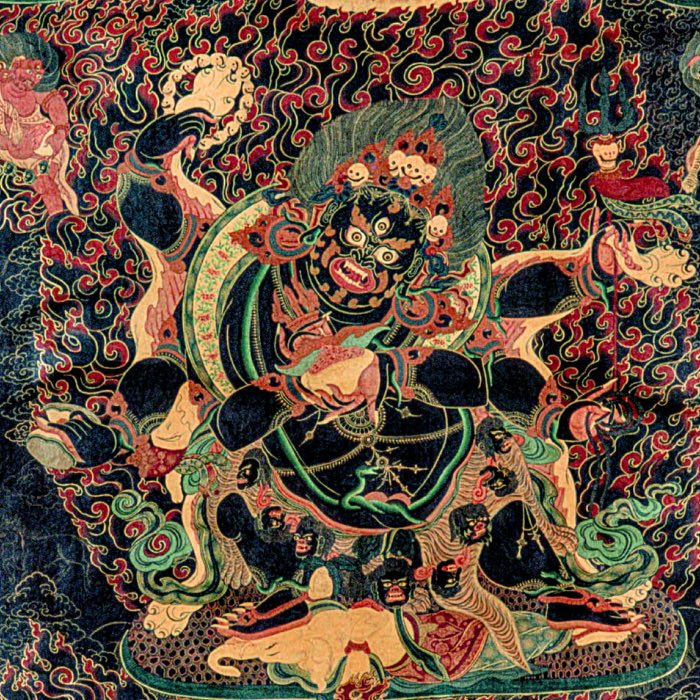

Rishukyo-Mandara, Anonymous painter, scroll painting (emakimono), ink and colors on paper, Japan, Edo period, 19th century. The Buddhist sutra of the principle of the perfection of wisdom (Prajñaparomita-naya-sutra) was introduced to Japan from China in the 9th century. The scroll copies an original from the Kamakura period (1185-1333) and shows eighteen ritual mandalas symbolizing the individual doctrines of the sutra.

Rishukyo-Mandara, Anonymous painter, scroll painting (emakimono), ink and colors on paper, Japan, Edo period, 19th century. The Buddhist sutra of the principle of the perfection of wisdom (Prajñaparomita-naya-sutra) was introduced to Japan from China in the 9th century. The scroll copies an original from the Kamakura period (1185-1333) and shows eighteen ritual mandalas symbolizing the individual doctrines of the sutra.

The creation of emakimono involves meticulous craftsmanship, where artists must balance text placement and image composition to maintain narrative flow and visual harmony. The scrolls are designed for intimate engagement, meant to be unrolled slowly, revealing the story piece by piece, which allows for a personal and immersive experience.

Emakimono not only reflects the artistic innovations of its time but also offers insights into the societal and cultural history of Japan. Through these scrolls, modern viewers gain access to the aesthetic preferences, social norms, and literary tastes of the periods they depict.

Comparison with European book illumination

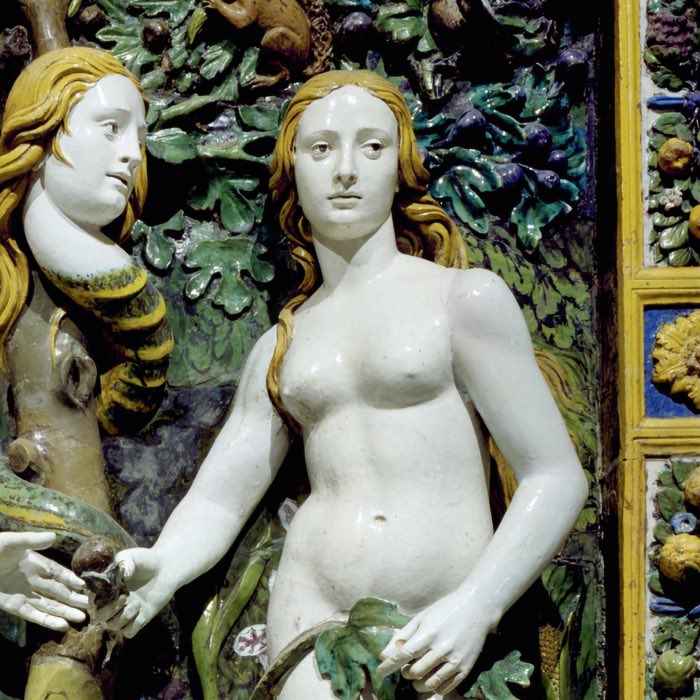

While emakimono shares similarities with Western art forms, particularly in its storytelling aspect, it can be interestingly compared with European book illumination of the Middle Ages. Both art forms involve the integration of text and image and served as mediums for narrative and religious storytelling. However, their artistic executions and cultural significances diverge significantly.

European illuminated manuscripts, like the Book of Kells or the Lindisfarne Gospels, are typically bound books, with each page providing a static frame for the artwork and text. The illuminations often use gold leaf and vibrant colors, with detailed borders and miniature illustrations that reflect the deep religiosity and the opulent tastes of the period.

In contrast, East Asian handscrolls are unbound and must be unrolled to be viewed, creating a dynamic and linear progression of the narrative that mimics the passing of time or movement through space. This format reflects the Eastern contemplative approach to art, inviting a more prolonged and personal engagement with the story.

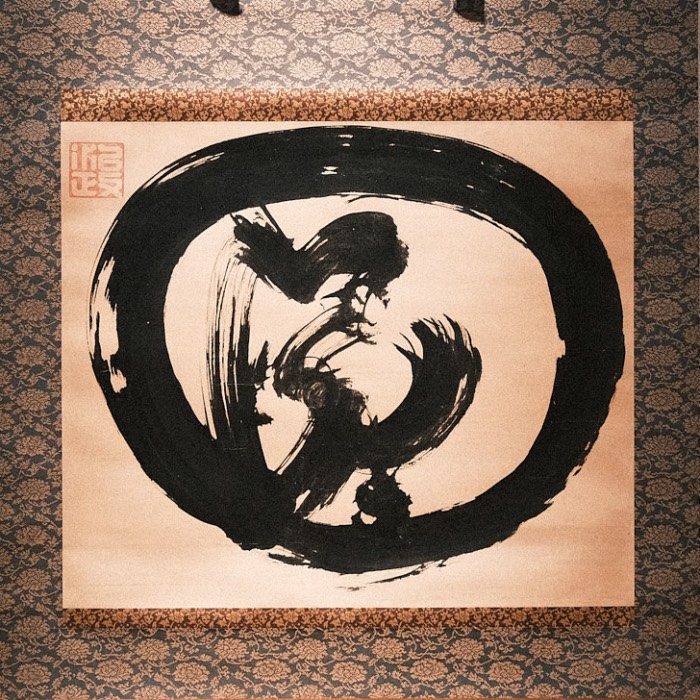

Cologne Missal (Missale Novum Diocesis Coloniensis), Print: Paris, Nicolas Prévost (printing house of Wolfgang Hopyl), 8 November 1525 for Arnold Birckman, Cologne Paper, coloured, Latin. One of the first printed missals in Cologne. The missal contains the texts of the Mass for the entire liturgical year. Seen in an exhbition at the Museum Schnütgen in Cologne

Cologne Missal (Missale Novum Diocesis Coloniensis), Print: Paris, Nicolas Prévost (printing house of Wolfgang Hopyl), 8 November 1525 for Arnold Birckman, Cologne Paper, coloured, Latin. One of the first printed missals in Cologne. The missal contains the texts of the Mass for the entire liturgical year. Seen in an exhbition at the Museum Schnütgen in Cologne

Conclusion

Emakimono, or Japanese handscrolls, offer a captivating glimpse into the convergence of art and literature in Japan. By intertwining text and imagery, these scrolls not only tell stories but also immerse the viewer in the aesthetic and cultural narratives of their era. This form of narrative art provides a personal and intimate experience, as each scroll is unrolled gradually, revealing its contents slowly and allowing for thoughtful engagement.

The comparison with European book illumination during the Middle Ages illuminates the unique artistic techniques and cultural contexts that distinguish Eastern and Western narrative traditions. Unlike the static and ornate pages of European manuscripts, emakimono unfolds dynamically, mirroring the flow of time and narrative progression in a linear format. This distinction highlights the Eastern contemplative approach to art, encouraging a deeper, more personal interaction with the story.

Furthermore, emakimono not only reflects the artistic innovations of its time but also serves as a cultural artifact, offering insights into the social norms, literary tastes, and philosophical beliefs of historical Japan. As such, these scrolls are more than just art; they are a bridge to understanding the rich historical and cultural landscapes of Japan and its neighbors.

Through ongoing preservation and scholarly study, emakimono continues to be an invaluable resource, enriching our understanding of the world’s artistic and literary heritage. This exploration of Japanese handscrolls sets the stage for further discussions on other traditional East Asian art forms, such as byobu (屏風folding screens), which will be the subject of my next post.

References and further reading

- Dietrich Seckel, Emakimono: The Art of the Japanese Painted Hand-Scrolls, 1959, Max Niehans Verlag AG Zurich, Switzerland

- Hideo Okudaira, Emaki: Japanese Picture Scrolls, 1962, Charles E Tuttle Company

- Matthi Forrer, Kakemono: Five Centuries Of Japanese Painting - The Perino Collection, 2020, Skira, ISBN: 9788857243795

- Harald Olbrich, Gerhard Strauß, Lexikon der Kunst - A - Cim, 1996, dtv Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG, ISBN: 9783423059060

- Gabriele Fahr-Becker, Ostasiatische Kunst, 2011, Ullmann, ISBN: 9783833160998

- Danielle Elisseeff, Vadime Elisseeff, Art Of Japan, 1985, ABRAMS, ISBN: 9780810906426

- Masako Watanabe, Storytelling In Japanese Art, 2011, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, ISBN: 9780300175905

- Adele Schlombs, Sybille Girmond, Meisterwerke aus China, Korea und Japan, 1995, Prestel, ISBN: 9783791314945

- Heinz Götze, Chinesische und Japanische Kalligraphie aus zwei Jahrtausenden, 1987, Prestel, ISBN: 9783791307954

- Clarissa Von Spee, Adele Schlombs, Der perfekte Pinsel - chinesische Malerei 1300 - 1900, 2010, Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, ISBN: 9783981261035

- Stephen Addiss, The Art Of Zen - Paintings And Calligraphy By Japanese Monks 1600-1925, 2018, Echo Point Books & Media, ISBN: 9781635610741

comments