Kakemono: The art of Japanese hanging scrolls

Kakemono (掛け物), or Japanese hanging scrolls, are a prominent feature in the traditional Japanese art landscape. These scrolls are designed to be displayed vertically and are often used to adorn the alcoves of Japanese homes, particularly in settings like the tea ceremony. The art of kakemono centers around the aesthetics of simplicity and seasonal change, making it a dynamic element of Japanese decor. In this post, we briefly explore the history and significance of kakemono in Japanese art and culture.

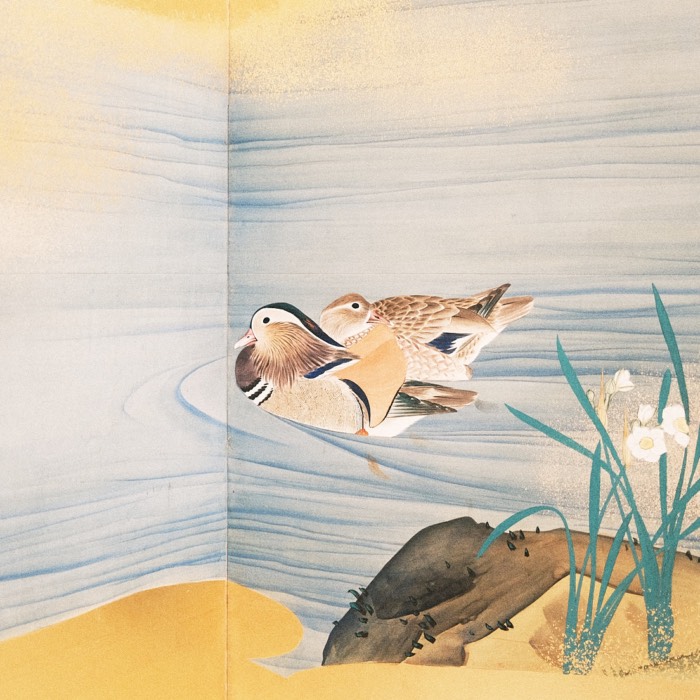

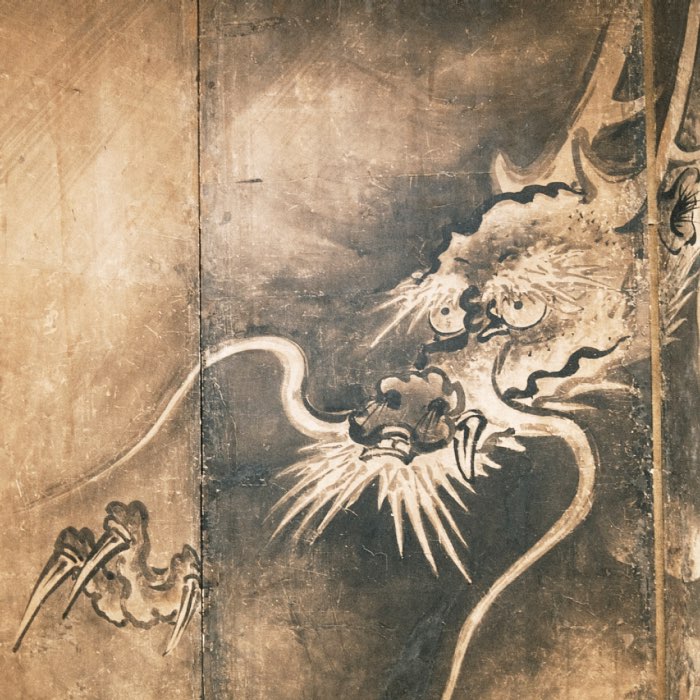

Exhibition hall at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne. In the center we see a large hanging scroll (kakemono) depicting the death of the Buddha. On the left, we see a part of a Tigar-and-Dragon folding screen (byōbu).

Exhibition hall at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne. In the center we see a large hanging scroll (kakemono) depicting the death of the Buddha. On the left, we see a part of a Tigar-and-Dragon folding screen (byōbu).

Origins from China

The concept of hanging scrolls or guàtú (掛圖) originated in China, where they have been a significant aspect of artistic expression since ancient times. Chinese hanging scrolls are known for their meticulous brushwork and elaborate landscapes, often accompanied by poetry that enhances the visual experience (see e.g. “The Three Perfections”). The format was adapted by Japanese artists, who got in contact with Chinese culture and art via trade and cultural and diplomatic exchange. The Japanese infused it with local artistic sensibilities and philosophical outlooks.

In China, the hanging scroll serves not just as decoration but as a focal point for contemplation. These scrolls are typically made of silk or paper and can feature a variety of subjects, including traditional calligraphy, landscapes, and scenes from mythology. The ability to roll these scrolls for storage and selectively display them allows for a personal interaction with the artwork, reflecting the Chinese cultural emphasis on the intimate connection between art and viewer.

Ensemble of three Chinese hanging scrolls (guàtú), exhibited in the 50 Years – 50 Treasures exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne.

Ensemble of three Chinese hanging scrolls (guàtú), exhibited in the 50 Years – 50 Treasures exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne.

Bodhidharma from the ensemble above, Duan Yongyuan (ca. 1811 - ca. 1912), hanging scroll, ink on paper, Republic of China, dated 1912 on the reverse. The legendary monk Bodhidharma (Chinese: Damo) is considered the first patriarch of Zen Buddhism. Painting, calligraphy and poetry serve as important methods in this movement to cultivate one’s own mind and open it to enlightenment.

Bodhidharma from the ensemble above, Duan Yongyuan (ca. 1811 - ca. 1912), hanging scroll, ink on paper, Republic of China, dated 1912 on the reverse. The legendary monk Bodhidharma (Chinese: Damo) is considered the first patriarch of Zen Buddhism. Painting, calligraphy and poetry serve as important methods in this movement to cultivate one’s own mind and open it to enlightenment.

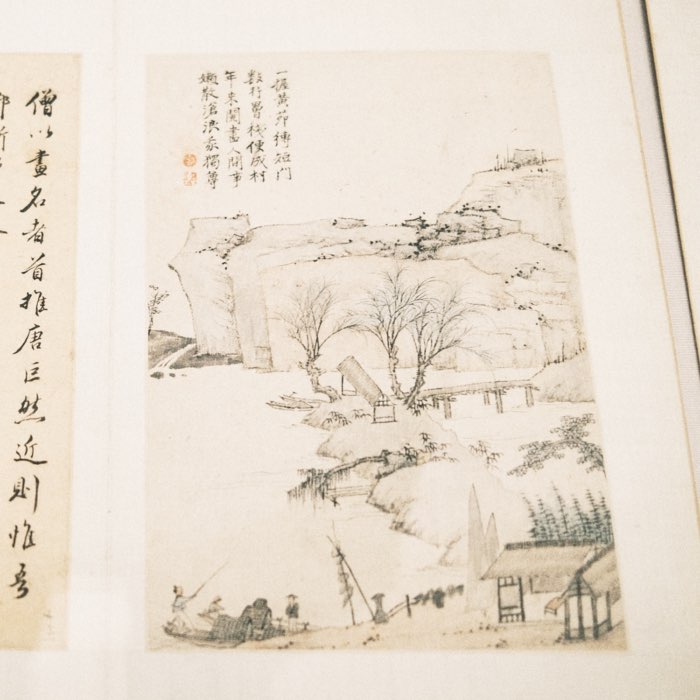

Daffodils on Taihu Rock from the ensemble above, Zhang Mu (1607-1687), ink and colors on paper, China, Qing dynasty, Kangxi period, dated 1670. The daffodil symbolizes happiness and prosperity, the tuft is associated with a group of immortals. The holey garden rock, which is traditionally harvested from Lake Taihu in Jiangsu, is also known as the “Stone of Long Life” (shoushi). Images of this type were used to send congratulations on New Year or a birthday.

Daffodils on Taihu Rock from the ensemble above, Zhang Mu (1607-1687), ink and colors on paper, China, Qing dynasty, Kangxi period, dated 1670. The daffodil symbolizes happiness and prosperity, the tuft is associated with a group of immortals. The holey garden rock, which is traditionally harvested from Lake Taihu in Jiangsu, is also known as the “Stone of Long Life” (shoushi). Images of this type were used to send congratulations on New Year or a birthday.

Adaptation and evolution in Japan

In Japan, the adaptation of the Chinese scroll led to the development of kakemono (掛け物, lit. “hanging thing”) or kakejiku (掛け軸, lit. “hanging scroll”), which embraced the Japanese minimalist aesthetic and a deep connection to nature and the changing seasons. This transformation is evident in the choice of subjects, which often relate directly to the time of year, playing a significant role in the spiritual and aesthetic ambiance of a room.

Kakemono are crafted with an awareness of the Zen principle of simplicity. They are more than just art pieces; they are a part of the living environment, reflecting the transient beauty of nature and the philosophical meditations of the viewer. The materials used, such as delicate rice paper and bamboo rollers, contribute to the overall subtlety and profoundness of the scroll.

Zen Circle (ensō and the character yume (dream)) by Deiryu (Kanshū Sojun, 1895 -1954), Japan, Showa period, c. 1925 - 1954, hanging scroll, ink on paper. Seen in an exhibition at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin.

Zen Circle (ensō and the character yume (dream)) by Deiryu (Kanshū Sojun, 1895 -1954), Japan, Showa period, c. 1925 - 1954, hanging scroll, ink on paper. Seen in an exhibition at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin.

Hotei pointing at the moon by Awakawa Yasuichi (1902-1976), Japan, Showa period, 20th c., hanging scroll, ink on paper. Seen in an exhibition at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin.

Hotei pointing at the moon by Awakawa Yasuichi (1902-1976), Japan, Showa period, 20th c., hanging scroll, ink on paper. Seen in an exhibition at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin.

Blind people crossing an abyss, Japan, Edo period, 18th c., hanging scroll, ink on paper. Inscription: “Inner life and the floating world are like the blind men’s round log bridge – an enlightened mind is the best guide”” (Translated by Stephen Addiss). Seen in an exhibition at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin.

Blind people crossing an abyss, Japan, Edo period, 18th c., hanging scroll, ink on paper. Inscription: “Inner life and the floating world are like the blind men’s round log bridge – an enlightened mind is the best guide”” (Translated by Stephen Addiss). Seen in an exhibition at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin.

Left: Hibiscus by Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795). Hanging scroll (kakemono), color on silk, dated 1772, Japan. Right: Carp by Itō Jakuchu (1716-1800, right). Hanging scroll (kakemono), ink on paper, late 18th century, Japan. According to a Chinese legend, a carp turned into a dragon after it had overcome a waterfall. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne.

Left: Hibiscus by Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795). Hanging scroll (kakemono), color on silk, dated 1772, Japan. Right: Carp by Itō Jakuchu (1716-1800, right). Hanging scroll (kakemono), ink on paper, late 18th century, Japan. According to a Chinese legend, a carp turned into a dragon after it had overcome a waterfall. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne.

Bodhidharma crossing the Yangzi on a reed, Fūgai Ekun (1568-1654), hanging scroll (kakemono), ink on paper Japan, 17th century. Bodhidharma’s life story was embellished with legends in China. After failing to convert the emperor of the Líang dynasty, he is said to have crossed the Yangzi on a reed to reach the Shaolin Monastery, where he spent nine years in front of a rock face and attained enlightenment. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Bodhidharma crossing the Yangzi on a reed, Fūgai Ekun (1568-1654), hanging scroll (kakemono), ink on paper Japan, 17th century. Bodhidharma’s life story was embellished with legends in China. After failing to convert the emperor of the Líang dynasty, he is said to have crossed the Yangzi on a reed to reach the Shaolin Monastery, where he spent nine years in front of a rock face and attained enlightenment. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

The character Enso, Ikeda Harumasa (1750-1818), hanging scroll (kakemono), ink on paper, Japan, Edo period, late 18th - early 19th century. Ikeda Harumasa was the fifth generation daimyō of the Bizen-Okayama fiefdom and temporary treasurer of the shōgun. The power and authority of his personality is expressed in his calligraphy. The character ‘en’ literally means ‘circle’ and alludes to the ‘roundness’ or perfection of the Lotus Sutra. The circle is also a symbol of the equality of all living beings propagated in Buddhism. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

The character Enso, Ikeda Harumasa (1750-1818), hanging scroll (kakemono), ink on paper, Japan, Edo period, late 18th - early 19th century. Ikeda Harumasa was the fifth generation daimyō of the Bizen-Okayama fiefdom and temporary treasurer of the shōgun. The power and authority of his personality is expressed in his calligraphy. The character ‘en’ literally means ‘circle’ and alludes to the ‘roundness’ or perfection of the Lotus Sutra. The circle is also a symbol of the equality of all living beings propagated in Buddhism. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Begging Monks, Returning Monks (1895-1954). Pair of hanging scrolls, ink on paper, hanging scroll (kakemono), inscriptions Deiryū, 20th century, after 1945, Japan. Zen monks traditionally used the art of the brush to cultivate their relationships with patrons and other monks, but it was not until the 18th century that the practice of using art to popularize Zen teachings among large sections of the population emerged. Gestural performance and spontaneity played an increasingly important role. This tradition continued into the 20th century and was referred to as zenga (Zen painting). Izawa Deiry, abbot of Enpuku-ji near Kyoto, is one of the best-known representatives of zenga. He simplified the composition and the individual figures to minimal lines, dots and circles. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Begging Monks, Returning Monks (1895-1954). Pair of hanging scrolls, ink on paper, hanging scroll (kakemono), inscriptions Deiryū, 20th century, after 1945, Japan. Zen monks traditionally used the art of the brush to cultivate their relationships with patrons and other monks, but it was not until the 18th century that the practice of using art to popularize Zen teachings among large sections of the population emerged. Gestural performance and spontaneity played an increasingly important role. This tradition continued into the 20th century and was referred to as zenga (Zen painting). Izawa Deiry, abbot of Enpuku-ji near Kyoto, is one of the best-known representatives of zenga. He simplified the composition and the individual figures to minimal lines, dots and circles. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Bodhidharma, attributed to Ashikaga Yashimochi (1386-1428), hanging scroll (kakemono), ink on paper, inscription by Shunsaku Zenkō (active 1425-1426), Japan, early 15th century. From the 14th century onwards, chest or head portraits showing Bodhdharma (Japanese: Doruma) in intense meditation with his eyes protruding became common. The Cologne painting is attributed to the fourth Ashikaga Shōgun and bears an inscription by the monk Shunsaku Zenka from Detoko-ji in Kyoto. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Bodhidharma, attributed to Ashikaga Yashimochi (1386-1428), hanging scroll (kakemono), ink on paper, inscription by Shunsaku Zenkō (active 1425-1426), Japan, early 15th century. From the 14th century onwards, chest or head portraits showing Bodhdharma (Japanese: Doruma) in intense meditation with his eyes protruding became common. The Cologne painting is attributed to the fourth Ashikaga Shōgun and bears an inscription by the monk Shunsaku Zenka from Detoko-ji in Kyoto. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Mount Fuji, attributed to Kanō Naonobu (1607-1650), Ink on paper, hanging scroll (kakemono), Japan, early Edo period, 17th century. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Mount Fuji, attributed to Kanō Naonobu (1607-1650), Ink on paper, hanging scroll (kakemono), Japan, early Edo period, 17th century. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Amida-Buddha, Mineral paint and gold on silk, hanging scroll (kakemono), Japan, late Muromachi period, early 16th century. The Buddha of the West with his paradise of Jōdo, the Pure Land, is one of the most important, most frequently depicted figures of the Buddhist pantheon. In the 13th century, the cult figures were shown not just between the mountains but alse floating down on “moving” clouds, thereby reflecting the inner turmoil of the devout and their hope of early redemption. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Amida-Buddha, Mineral paint and gold on silk, hanging scroll (kakemono), Japan, late Muromachi period, early 16th century. The Buddha of the West with his paradise of Jōdo, the Pure Land, is one of the most important, most frequently depicted figures of the Buddhist pantheon. In the 13th century, the cult figures were shown not just between the mountains but alse floating down on “moving” clouds, thereby reflecting the inner turmoil of the devout and their hope of early redemption. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

From left to right: Aizen myōō (hanging scroll (kakemono), ink, colours, gold on silk, Japan, late Kamakura period, 13th- early 14th century), Fudō myōō (hanging scroll (kakemono), ink, colours, gold on silk, registered ‘Important Cultural Property’ (jūyō bunkazai), Japan, Nanbokucho period, late 14th century), and Amida-Buddha (mineral paint and gold on silk, Japan, late Muromachi period, early 16th century). Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

From left to right: Aizen myōō (hanging scroll (kakemono), ink, colours, gold on silk, Japan, late Kamakura period, 13th- early 14th century), Fudō myōō (hanging scroll (kakemono), ink, colours, gold on silk, registered ‘Important Cultural Property’ (jūyō bunkazai), Japan, Nanbokucho period, late 14th century), and Amida-Buddha (mineral paint and gold on silk, Japan, late Muromachi period, early 16th century). Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Fudō myōō, hanging scroll (kakemono), ink, colours, gold on silk, registered ‘Important Cultural Property’ (jūyō bunkazai), Japan, Nanbokucho period, late 14th century. Fudō myōō is regarded as an emanation of the highest Buddha Vairocana (Dainichi nyorai). In popular religion, he has become protector of rocks and water fals and is seen as the ‘original Buddhist form’ (honji-butsu) of several Shinto Gods. The sword surrounded by a dragon in the top left corner represents the ‘Flaming sword of Knowledge’ which symbolizes his ‘transformation body. The hanging scroll was owned by the Shingon temple Ryogon-ji in Ayabe, Kyoto prefecture, and is registred in Japan as ‘Important Cultural Property’ (jūyō bunkazai).

Fudō myōō, hanging scroll (kakemono), ink, colours, gold on silk, registered ‘Important Cultural Property’ (jūyō bunkazai), Japan, Nanbokucho period, late 14th century. Fudō myōō is regarded as an emanation of the highest Buddha Vairocana (Dainichi nyorai). In popular religion, he has become protector of rocks and water fals and is seen as the ‘original Buddhist form’ (honji-butsu) of several Shinto Gods. The sword surrounded by a dragon in the top left corner represents the ‘Flaming sword of Knowledge’ which symbolizes his ‘transformation body. The hanging scroll was owned by the Shingon temple Ryogon-ji in Ayabe, Kyoto prefecture, and is registred in Japan as ‘Important Cultural Property’ (jūyō bunkazai).

Aizen myōō, hanging scroll (kakemono), ink, colours, gold on silk, Japan, late Kamakura period, 13th- early 14th century. Similar to Fudō, Aizen myōō belongs to the group of kings of esoteric knowledge in the pantheon of Japanese secret Buddhist teachings. Like the other Wisdom Kings, Aizen is on the same hierarchical level as the boddhisatvas, illustrated in this picture by the typical golden chest jewellery, arm bands and anklets as well as the large golden ear jewellery, and the white ribbons braided into the hair behind the ears. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Aizen myōō, hanging scroll (kakemono), ink, colours, gold on silk, Japan, late Kamakura period, 13th- early 14th century. Similar to Fudō, Aizen myōō belongs to the group of kings of esoteric knowledge in the pantheon of Japanese secret Buddhist teachings. Like the other Wisdom Kings, Aizen is on the same hierarchical level as the boddhisatvas, illustrated in this picture by the typical golden chest jewellery, arm bands and anklets as well as the large golden ear jewellery, and the white ribbons braided into the hair behind the ears. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Left: Mandala of the Kasuga Shrines, coloured paint and gold on silk, hanging scroll (kakemono), Japan, Nanbokucho period, 2nd half of the 14th century. The picture shows the sacred landscape with Mount Kasuga and Mount Mikasa in the background. Four Shinto shrines are arranged in a row, surrounded by cloister-like corridors. A fifth shrine stands across from the sanctuary. The shrines are dedicated to the five deities of the powerful Fujiwara family, who relocated when the capital was moved from Asuka to Heijo (today known as Nara) in the region of Mount Kasuga in 710. The two pagodas in the foreground form part of the Buddhist Köfukuji Temple and were also moved from Asuka to Nara as the temples of the Fujiwara clan. The five Kasuga gods are depicted in the guise of five cult figures of the Buddhist pantheon, floating on the clouds above the two mountains. To peacefully assimilate the foreign religion of Buddhism in Japan, attempts were made to connect Shintoism and Buddhism at an early stage by declaring that the Shinto gods were manifestations of Buddhist deities. Accordingly, they appear in their Buddhist “archetypes” in the pictures shown here. In all likeli-hood, this fusion of Shintoism and Buddhism did not meet any major opposition because the local deities had not been portrayed in images until this time. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Left: Mandala of the Kasuga Shrines, coloured paint and gold on silk, hanging scroll (kakemono), Japan, Nanbokucho period, 2nd half of the 14th century. The picture shows the sacred landscape with Mount Kasuga and Mount Mikasa in the background. Four Shinto shrines are arranged in a row, surrounded by cloister-like corridors. A fifth shrine stands across from the sanctuary. The shrines are dedicated to the five deities of the powerful Fujiwara family, who relocated when the capital was moved from Asuka to Heijo (today known as Nara) in the region of Mount Kasuga in 710. The two pagodas in the foreground form part of the Buddhist Köfukuji Temple and were also moved from Asuka to Nara as the temples of the Fujiwara clan. The five Kasuga gods are depicted in the guise of five cult figures of the Buddhist pantheon, floating on the clouds above the two mountains. To peacefully assimilate the foreign religion of Buddhism in Japan, attempts were made to connect Shintoism and Buddhism at an early stage by declaring that the Shinto gods were manifestations of Buddhist deities. Accordingly, they appear in their Buddhist “archetypes” in the pictures shown here. In all likeli-hood, this fusion of Shintoism and Buddhism did not meet any major opposition because the local deities had not been portrayed in images until this time. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Stag Mandala from the ensemble above, mineral paint and gold on silk, hanging scroll (kakemono), Japan, late Kamakura to Nanbokucho period, approx. mid-14th century. As a messenger of the gods of Mount Kasuga, the stag bears a sacred Sakaki branch (Cleyera japonica) on its saddle. The five Shinto deities of Mount Kasuga who are being invoked appear against a gold back-ground. However, they are shown in their assumed Buddhist archetypal form: the historical Buddha in the centre, below which, clockwise, Yakushi, the Buddha of Healing, and the Bodhisattvas Jizo, the eleven-headed Kannon and Monju. The gold disc is a link between the projection disc of esoteric Buddhism and the mirror as the embodiment of the sun goddess. In the background of the night sky Mount Kasuga stands proud in front of Mount Mikasa. As extolled in poetry, where the moon rises above the Mikasa-yama is the home of the Kasuga gods. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Stag Mandala from the ensemble above, mineral paint and gold on silk, hanging scroll (kakemono), Japan, late Kamakura to Nanbokucho period, approx. mid-14th century. As a messenger of the gods of Mount Kasuga, the stag bears a sacred Sakaki branch (Cleyera japonica) on its saddle. The five Shinto deities of Mount Kasuga who are being invoked appear against a gold back-ground. However, they are shown in their assumed Buddhist archetypal form: the historical Buddha in the centre, below which, clockwise, Yakushi, the Buddha of Healing, and the Bodhisattvas Jizo, the eleven-headed Kannon and Monju. The gold disc is a link between the projection disc of esoteric Buddhism and the mirror as the embodiment of the sun goddess. In the background of the night sky Mount Kasuga stands proud in front of Mount Mikasa. As extolled in poetry, where the moon rises above the Mikasa-yama is the home of the Kasuga gods. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Example of a large hangin scroll (kakemono), showing the death of the historical Buddha, depicting the Buddha’s entrance into perfect nirvana. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Example of a large hangin scroll (kakemono), showing the death of the historical Buddha, depicting the Buddha’s entrance into perfect nirvana. Seen in an exhibition at the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Cologne, in August 2024.

Example of a moder kakemono: Arhat Rahula (Rakan Ragora, 羅漢羅怙羅尊者), Munakata Shikō (棟方志功, 1903 - 1975), Japan, Showa period, 1939, woodblock print mounted as a hanging scroll (kakemono), ink on paper. Munakata Shiko is regarded as one of the great individualist woodblock (ukiyo-e) artists in 20th century, Japan. Originally trained in oil painting, he created his prints on his own (i.e. without the help of block carvers and/or printers) as artistic graphics. However, the themes of his prints are often taken from tradition and refer to Buddhism or folk tales. He was close to the so-called Folk Craft Movement, and enjoyed an international career. He won awards for his prints at the São Paulo Biennial in 1955 and the Biennale di Venezia in 1956. The group of works decorated in São Paulo contained this print. Ragora, depicted here, is commonly regarded as the eleventh in a group of sixteen rakan and son of the historical Buddha. However, in Munakata’s work he is one of a group of ten disciples of the Buddha, which is especially venerated in the tradition of Buddhism known as Zen. Seen in an exhibition at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin.

Example of a moder kakemono: Arhat Rahula (Rakan Ragora, 羅漢羅怙羅尊者), Munakata Shikō (棟方志功, 1903 - 1975), Japan, Showa period, 1939, woodblock print mounted as a hanging scroll (kakemono), ink on paper. Munakata Shiko is regarded as one of the great individualist woodblock (ukiyo-e) artists in 20th century, Japan. Originally trained in oil painting, he created his prints on his own (i.e. without the help of block carvers and/or printers) as artistic graphics. However, the themes of his prints are often taken from tradition and refer to Buddhism or folk tales. He was close to the so-called Folk Craft Movement, and enjoyed an international career. He won awards for his prints at the São Paulo Biennial in 1955 and the Biennale di Venezia in 1956. The group of works decorated in São Paulo contained this print. Ragora, depicted here, is commonly regarded as the eleventh in a group of sixteen rakan and son of the historical Buddha. However, in Munakata’s work he is one of a group of ten disciples of the Buddha, which is especially venerated in the tradition of Buddhism known as Zen. Seen in an exhibition at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin.

Connection to Korean hanging scrolls

The Korean tradition of hanging scrolls, while influenced by Chinese practices, also shares a kinship with Japanese kakemono. Korean scrolls often emphasize themes of simplicity and nature but tend to employ a more restrained palette and less ornate compositions compared to their Chinese counterparts. This reflects a unique Korean aesthetic that values understatement and a deep, often spiritual engagement with the natural world.

Like in Japan, Korean hanging scrolls are used in both secular and religious contexts, enhancing the environment with their serene and contemplative qualities. The artistry in Korean scrolls, like the Japanese kakemono, is not just in the painting or calligraphy itself but in the overall presentation, which includes the careful selection of mounting fabrics and the precise placement within a space.

Info: Unfortunatly, I don’t have any pictures of Korean hanging scrolls. I will try to get some and add them here as soon as possible. If you know the best place to find Korean hanging scrolls, please let me know in the comments below.

Cultural significance and contemporary relevance

Today, kakemono remains a celebrated form of art in Japan and is revered for its ability to convey depth and emotion in a restrained format. The tradition of hanging scrolls across China, Japan, and Korea highlights a shared cultural heritage while also showcasing the distinct interpretations and values of each culture.

The ongoing appreciation and study of kakemono and other East Asian hanging scrolls underscore their enduring appeal and the continuous relevance of traditional arts in modern times. As collectors and museums around the world seek to preserve and understand these pieces, the hanging scroll remains a vital link to the historical and cultural narratives of East Asia.

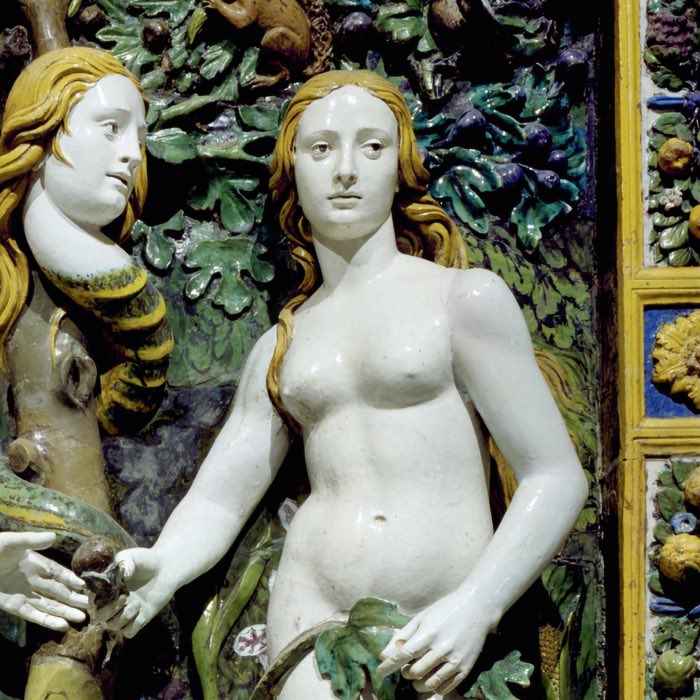

However, the tradition of hanging scrolls is not limited to East Asia. In the West, artists have also embraced the format, adapting it to suit their own aesthetic sensibilities. The hanging scroll has become a versatile art form that transcends cultural boundaries and continues to captivate audiences worldwide. And also in East Asia itself, the tradition of hanging scrolls is still alive and well, with contemporary artists creating innovative and thought-provoking works that push the boundaries of the medium.

In case you see a scroll not in vertical form but in horizontal form and enrolled, e.g., on a table, that’s called an emakimono (絵巻物) and not a kakemono. I will write about emakimono in the next post. Stay tuned.

References and further reading

- Matthi Forrer, Kakemono: Five Centuries Of Japanese Painting - The Perino Collection, 2020, Skira, ISBN: 9788857243795

- Harald Olbrich, Gerhard Strauß, Lexikon der Kunst - A - Cim, 1996, dtv Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG, ISBN: 9783423059060

- Gabriele Fahr-Becker, Ostasiatische Kunst, 2011, Ullmann, ISBN: 9783833160998

- Danielle Elisseeff, Vadime Elisseeff, Art Of Japan, 1985, ABRAMS, ISBN: 9780810906426

- Masako Watanabe, Storytelling In Japanese Art, 2011, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, ISBN: 9780300175905

- Adele Schlombs, Sybille Girmond, Meisterwerke aus China, Korea und Japan, 1995, Prestel, ISBN: 9783791314945

- Heinz Götze, Chinesische und Japanische Kalligraphie aus zwei Jahrtausenden, 1987, Prestel, ISBN: 9783791307954

- Clarissa Von Spee, Adele Schlombs, Der perfekte Pinsel - chinesische Malerei 1300 - 1900, 2010, Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, ISBN: 9783981261035

- Stephen Addiss, The Art Of Zen - Paintings And Calligraphy By Japanese Monks 1600-1925, 2018, Echo Point Books & Media, ISBN: 9781635610741

- Uta Werlich, Entdeckung Korea! - Schätze aus deutschen Museen, 2011, The Korea Foundation, ISBN: 9788986090413

comments