Exploring Buddhist and East Asian art in Cologne

Cologne, a city rich in Christian history and culture, also offers a unique opportunity for enthusiasts of Buddhist and East Asian art. The city is home to two remarkable institutions: the Museum of East Asian Art and the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum. Here some of my favorite pieces from both museums.

Museum of East Asian Art

Established in 1913, the Museum of East Asian Artꜛ (German: Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst) stands as a testament to the beauty and complexity of Buddhist and East Asian art. It is one of the few museums outside Asia dedicated exclusively to East Asian art, making it a rare gem in Europe. The museum is not huge, but its collection is extensive, encompassing a range of artifacts from China, Japan, and Korea, with frequent special exhibitions on specific themes or regions. The museum’s shop also offers a variety of books and souvenirs for those interested in learning more about East Asian art, culture and history.

The museum has its roots in the early 20th century, a period marked by a growing European interest in East Asian culture. Founded in 1913, it emerged from a private collection of Adolf Fischer and his wife Frieda Bartdorff, both enthusiasts of East Asian art. Their extensive travels and passion for collecting art from China, Japan, and Korea laid the foundation for one of Europe’s first museums dedicated to East Asian art. This museum was born out of a desire to create a space for cultural dialogue and to provide a deeper understanding of East Asian civilizations, contrasting with the then-common Orientalist perspectives. It represents a significant shift in the Western perception of East Asian art, from exotic curiosity to genuine appreciation and scholarly interest.

The Museum for East Asian Art is located directly at the Aachener Weiher, a popular park in Cologne, into which it is seamlessly integrated.

The Museum for East Asian Art is located directly at the Aachener Weiher, a popular park in Cologne, into which it is seamlessly integrated.

Entrance hall of the Museum for East Asian Art.

Entrance hall of the Museum for East Asian Art.

The stone garden in the courtyard of the Museum for East Asian Art. The garden resembles traditional Japanese stone gardens, which are often found in Zen temples.

The stone garden in the courtyard of the Museum for East Asian Art. The garden resembles traditional Japanese stone gardens, which are often found in Zen temples.

Usagi Kannon II by Leiko Ikemura. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Usagi Kannon II by Leiko Ikemura. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Chinese sculpture. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Chinese sculpture. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

A statue of Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (Guanyin in Chinese and Kannon in Japan). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

A statue of Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (Guanyin in Chinese and Kannon in Japan). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Dragon jar, Porcelain, Kumsari kiln, underglaze-blue, Korea, Joseon period, 18th century. Around 1450, Korea started making blue-and white porcelain. This jor was a ceremonial vessel used at the court for wine or flower sacrifices. As in China, the dragon represents Imperial power in Korea.

Dragon jar, Porcelain, Kumsari kiln, underglaze-blue, Korea, Joseon period, 18th century. Around 1450, Korea started making blue-and white porcelain. This jor was a ceremonial vessel used at the court for wine or flower sacrifices. As in China, the dragon represents Imperial power in Korea.

Kakemono (japanese hanging scroll) with a Japanese calligraphy. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Kakemono (japanese hanging scroll) with a Japanese calligraphy. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

A statue of Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

A statue of Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

A statue of Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

A statue of Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

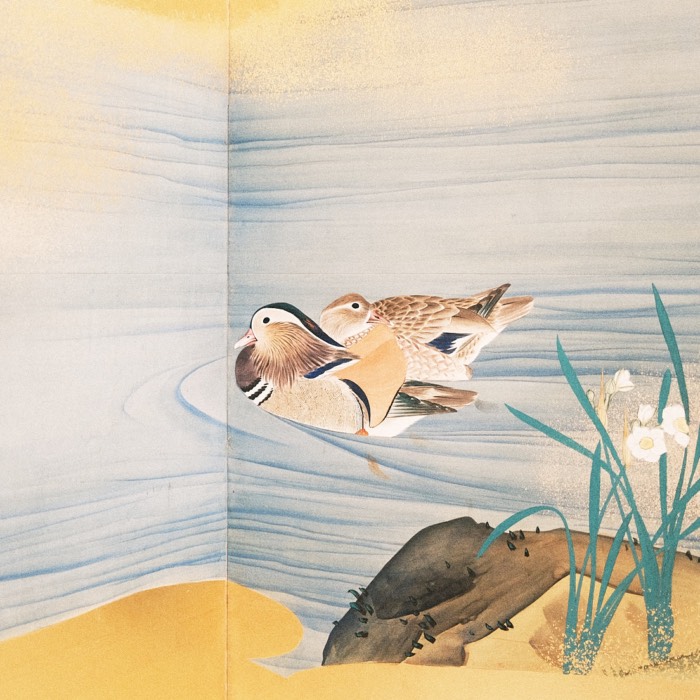

Detail of byobu (japanese folding screen) with a painting of a dragon. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Detail of byobu (japanese folding screen) with a painting of a dragon. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

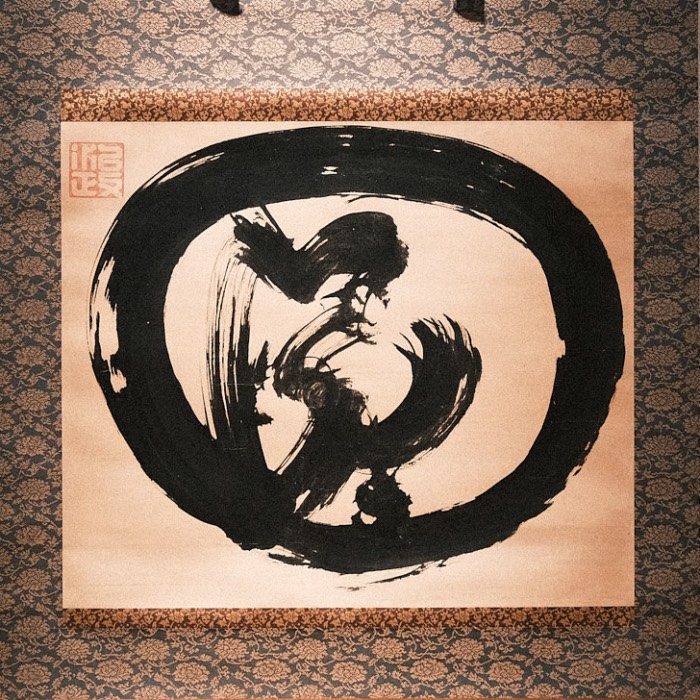

Kakemono, showing an ensō (a so-called Zen-circle), by Ikeda Harumasa (1750-1818), ink on paper, #Edo period, end of 18th - beginning of 19th century. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Kakemono, showing an ensō (a so-called Zen-circle), by Ikeda Harumasa (1750-1818), ink on paper, #Edo period, end of 18th - beginning of 19th century. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

A statue of a Bodhisattva. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

A statue of a Bodhisattva. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Kakemono, showing Fudō Myōō (Sanskrit: Acala), a dharma-protector. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Kakemono, showing Fudō Myōō (Sanskrit: Acala), a dharma-protector. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Kakemono, showing Bodhidharma (Japanese: Daruma), by Ashikaga Yoshimochi (1386-1428), ink on paper, inscription by Shunsoku Zenkō (active 1425-1426), early 15th century. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Kakemono, showing Bodhidharma (Japanese: Daruma), by Ashikaga Yoshimochi (1386-1428), ink on paper, inscription by Shunsoku Zenkō (active 1425-1426), early 15th century. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Kakemono, showing Bodhidharma (Japanese: Daruma). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Kakemono, showing Bodhidharma (Japanese: Daruma). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Detail of a large image called “The Death of Buddha”, Japan, ink on paper. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Detail of a large image called “The Death of Buddha”, Japan, ink on paper. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

The ghost of the maid Okiku who was killed and thrown in the well after she broke one of her lord’s plates rising up, by Hokusai, from One Hundred Ghost Tales, ca. 1830s, Japanese color WoodblockPrint (ukiyo-e). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

The ghost of the maid Okiku who was killed and thrown in the well after she broke one of her lord’s plates rising up, by Hokusai, from One Hundred Ghost Tales, ca. 1830s, Japanese color WoodblockPrint (ukiyo-e). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Inrō, a traditional Japanese case for holding small objects, such as medicine and seals. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

Inrō, a traditional Japanese case for holding small objects, such as medicine and seals. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne.

The stone garden covered by snow.

The stone garden covered by snow.

Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum

While the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museumꜛ is primarily known for its ethnographic collections, it also houses a noteworthy collection of Buddhist art, primarily from Southeast Asia. This collection offers a different perspective on Buddhist art, focusing on the regions beyond East Asia.

The Southeast Asian collection includes a range of Buddhist statues, ritual objects, and textiles. These artifacts highlight the diversity of Buddhist art as it spread across different cultures and regions. The museum also occasionally hosts special exhibitions on Buddhist art and culture, providing a more in-depth look at specific themes or regions.

Established in 1901, the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum was named after the ethnographer Wilhelm Joest, whose extensive travels and collections formed the basis of the museum. The museum’s evolution reflects a broader European fascination with ‘exotic’ cultures during the colonial era. However, unlike many ethnographic museums of its time, the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum has continually evolved to approach its exhibits with a more critical and respectful perspective towards the cultures represented. The inclusion of Buddhist art, particularly from Southeast Asia, in its collection is not only a statement about the diversity of its holdings but also about the museum’s commitment to showcasing the richness of global cultures. This approach marks a shift from viewing these artifacts as mere colonial trophies to recognizing them as integral parts of the world’s cultural heritage.

The Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum as seen from the opposite Belgisches Haus.

The Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum as seen from the opposite Belgisches Haus.

The entrance hall of the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum.

The entrance hall of the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum.

Buddha Statues. Left: Crowned Buddha. The Buddha holds both hands in a mirror-like gesture of vitarka mudra. Originally, Buddha was depicted unadorned as a monk. From the 10th/11th century onwards - initially in the East Indies - Buddha images were also adorned with a crown and rich jewels. Arm rings and belts lie above the outer garment and not, as one would expect, below it. This leads to the conclusion that they were originally placed on the sculptures as genuine jewelry, as is the case with female portraits. Thailand, Khmer period, Angkor Wat style - ca. 1150-1177 - bronze. Center: Buddha. The figure stands on a double lotus pedestal. Both hands are turned outwards in the gesture of vitarka mudra, the palms decorated with lotus blossoms. Buddha is clothed in an upper robe covering both shoulders. The lower robe with belt is visible beneath the upper robe. The linear treatment of the robe hems contrasts with the emphatically sculptural shaping of the lips and ears. Lop Buri, Thailand - 14th century, bronze. Right: Crowned Buddha. The Buddha holds his two hands in mirror image in the gesture of fearlessness and protection abhaya mudra, with which he once confronted a wild elephant. Thailand, Khmer period - ca. 1150 - 1177, bronze.

Buddha Statues. Left: Crowned Buddha. The Buddha holds both hands in a mirror-like gesture of vitarka mudra. Originally, Buddha was depicted unadorned as a monk. From the 10th/11th century onwards - initially in the East Indies - Buddha images were also adorned with a crown and rich jewels. Arm rings and belts lie above the outer garment and not, as one would expect, below it. This leads to the conclusion that they were originally placed on the sculptures as genuine jewelry, as is the case with female portraits. Thailand, Khmer period, Angkor Wat style - ca. 1150-1177 - bronze. Center: Buddha. The figure stands on a double lotus pedestal. Both hands are turned outwards in the gesture of vitarka mudra, the palms decorated with lotus blossoms. Buddha is clothed in an upper robe covering both shoulders. The lower robe with belt is visible beneath the upper robe. The linear treatment of the robe hems contrasts with the emphatically sculptural shaping of the lips and ears. Lop Buri, Thailand - 14th century, bronze. Right: Crowned Buddha. The Buddha holds his two hands in mirror image in the gesture of fearlessness and protection abhaya mudra, with which he once confronted a wild elephant. Thailand, Khmer period - ca. 1150 - 1177, bronze.

Votive plaque with standing Buddha. The exceptionally fine gold relief shows Buddha, whose hands are performing the gesture dharmachakra mudra ‘turning the wheel of teaching’. The gesture refers to his first sermon after his enlightenment. The remnants of the sweet-smelling reddish sandalwood paste, with which the relief was rubbed on both sides for worship, are still present in traces. Myanmar, Pegu Empire, Mon, 7th-9th century, gold.

Votive plaque with standing Buddha. The exceptionally fine gold relief shows Buddha, whose hands are performing the gesture dharmachakra mudra ‘turning the wheel of teaching’. The gesture refers to his first sermon after his enlightenment. The remnants of the sweet-smelling reddish sandalwood paste, with which the relief was rubbed on both sides for worship, are still present in traces. Myanmar, Pegu Empire, Mon, 7th-9th century, gold.

Buddha head. The full, emphatically oval face without a separating headband, the two-part arch of the hairline that follows the eyebrows, the thick rounded curls and the high domed skull outgrowth with flame are typical of the Ayutthaya style of the early 15th century. Thailand, Ayutthaya, early 15th century, bronze.

Buddha head. The full, emphatically oval face without a separating headband, the two-part arch of the hairline that follows the eyebrows, the thick rounded curls and the high domed skull outgrowth with flame are typical of the Ayutthaya style of the early 15th century. Thailand, Ayutthaya, early 15th century, bronze.

Buddha head. The head probably comes from Borobudur on Java, the most important Buddhist sanctuary in Indonesia. The visitor experiences it as a gigantic, three-dimensional mandala. Accompanied on both sides by reliefs, they ascend from the earthly plane of desires through the world of forms without desires, past 432 larger-than-life seated Buddha statues, up to the formless world on three round platforms, where 72 Buddhas sit half-hidden in stupas with lattice-like openwork walls. Borobudur, Central Java, Indonesia around 800, lava stone.

Buddha head. The head probably comes from Borobudur on Java, the most important Buddhist sanctuary in Indonesia. The visitor experiences it as a gigantic, three-dimensional mandala. Accompanied on both sides by reliefs, they ascend from the earthly plane of desires through the world of forms without desires, past 432 larger-than-life seated Buddha statues, up to the formless world on three round platforms, where 72 Buddhas sit half-hidden in stupas with lattice-like openwork walls. Borobudur, Central Java, Indonesia around 800, lava stone.

Head of a Buddha statue. The youthful-looking head belonged to the larger-than-life statue of a seated or standing Buddha, which is characterized by its special ‘beauty features’ - the overlong earlobes, the snail-shaped locks of hair and the skull outgrowth with a flame. Thailand, Ayutthaya, 14th/15th century, bronze, gilding.

Head of a Buddha statue. The youthful-looking head belonged to the larger-than-life statue of a seated or standing Buddha, which is characterized by its special ‘beauty features’ - the overlong earlobes, the snail-shaped locks of hair and the skull outgrowth with a flame. Thailand, Ayutthaya, 14th/15th century, bronze, gilding.

Buddha torso. The fragment belonged to an elegant seated Buddha figure, whose right hand was probably pointing downwards in a gesture of reaching for the earth. The surface shows the jade-green patina typical of bronzes from northern Thailand. Northern Thailand, Lan Na Thai, c. 1500, bronze.

Buddha torso. The fragment belonged to an elegant seated Buddha figure, whose right hand was probably pointing downwards in a gesture of reaching for the earth. The surface shows the jade-green patina typical of bronzes from northern Thailand. Northern Thailand, Lan Na Thai, c. 1500, bronze.

Votive plaque. The walking Buddha has raised his left hand in the gesture of fearlessness abhaya mudra. The motif of the walking Buddha refers to the enlightened Buddha’s visit to Tavatimsa heaven, where he preached to the gods there and to his mother. Buddha then returned to the earthly world on a staircase. The type of the descending Buddha was only sculpted in Thailand. Thailand, Ayutthaya, 1st half of the 15th century, pewter.

Votive plaque. The walking Buddha has raised his left hand in the gesture of fearlessness abhaya mudra. The motif of the walking Buddha refers to the enlightened Buddha’s visit to Tavatimsa heaven, where he preached to the gods there and to his mother. Buddha then returned to the earthly world on a staircase. The type of the descending Buddha was only sculpted in Thailand. Thailand, Ayutthaya, 1st half of the 15th century, pewter.

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara can be recognized by the small seated figure of Buddha Amitabha in front of his high crown of hair. Avalokiteshvara holds a prayer cord in his upper right hand and a book in his upper left. The face with half-closed eyes and smiling mouth corresponds to the ideal of a royal portrait at the time. Thailand, Khmer period, 13th century Sandstone.

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara can be recognized by the small seated figure of Buddha Amitabha in front of his high crown of hair. Avalokiteshvara holds a prayer cord in his upper right hand and a book in his upper left. The face with half-closed eyes and smiling mouth corresponds to the ideal of a royal portrait at the time. Thailand, Khmer period, 13th century Sandstone.

Eleven-headed Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. The bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara appears to the believer with a halo of helping arms. His eleven heads characterize him as Ekadashamukha Avalokiteshvara, the eleven-headed Lord of the World. According to legend, Avalokiteshvara’s head burst into ten pieces as he pondered the sufferings of this world. Out of compassion, the transcendent Buddha Amitabha formed ten heads from the pieces and added his own as the eleventh. Tibet, 15th/16th century - Fire-gilded bronze, turquoise, coral.

Eleven-headed Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. The bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara appears to the believer with a halo of helping arms. His eleven heads characterize him as Ekadashamukha Avalokiteshvara, the eleven-headed Lord of the World. According to legend, Avalokiteshvara’s head burst into ten pieces as he pondered the sufferings of this world. Out of compassion, the transcendent Buddha Amitabha formed ten heads from the pieces and added his own as the eleventh. Tibet, 15th/16th century - Fire-gilded bronze, turquoise, coral.

Footprint of the Buddha. The monumental stone slab shows the imprint of Buddha buddhapada’s left foot. Two nagas surround it. The Buddha’s footprint symbolizes his earthly presence after he has entered nirvana. The surface of the foot is filled with 108 emblems symbolizing the cosmos. These include the heavens, represented by pavilions, the Seven Mountains and Seven Oceans, the Four Continents, the Sun and the Moon. Shen replica, Myanmar, 18th-19th century, sandstone, color.

Footprint of the Buddha. The monumental stone slab shows the imprint of Buddha buddhapada’s left foot. Two nagas surround it. The Buddha’s footprint symbolizes his earthly presence after he has entered nirvana. The surface of the foot is filled with 108 emblems symbolizing the cosmos. These include the heavens, represented by pavilions, the Seven Mountains and Seven Oceans, the Four Continents, the Sun and the Moon. Shen replica, Myanmar, 18th-19th century, sandstone, color.

Buddha Shakyamuni. Buddha in the lotus position points to the ground with his right hand in the gesture of the earth invocation bhumisparsa mudra. This hand position has two meanings: firstly, it symbolizes the defeat of the demon Mara, who attempted to disturb Buddha in deep meditation. Secondly, Buddha used this gesture to call upon the earth as a witness when he finally experienced his enlightenment under the Bodhi tree after long meditation. Myanmar, 19th century, bronze, lacquer, gold.

Buddha Shakyamuni. Buddha in the lotus position points to the ground with his right hand in the gesture of the earth invocation bhumisparsa mudra. This hand position has two meanings: firstly, it symbolizes the defeat of the demon Mara, who attempted to disturb Buddha in deep meditation. Secondly, Buddha used this gesture to call upon the earth as a witness when he finally experienced his enlightenment under the Bodhi tree after long meditation. Myanmar, 19th century, bronze, lacquer, gold.

Tile with Mara’s followers. The two cat-headed figures in Burmese costume are armed with serrated discus disks. They are part of the force sent by the demon Mara to disrupt the Buddha’s meditation on the eve of his enlightenment. A sequence of ceramic plates with motifs of the terrifying demon army probably once adorned a stupa or temple. Myanmar, Pegu Empire, 15th century, stoneware, glaze.

Tile with Mara’s followers. The two cat-headed figures in Burmese costume are armed with serrated discus disks. They are part of the force sent by the demon Mara to disrupt the Buddha’s meditation on the eve of his enlightenment. A sequence of ceramic plates with motifs of the terrifying demon army probably once adorned a stupa or temple. Myanmar, Pegu Empire, 15th century, stoneware, glaze.

Stupa fragment. The fragment was part of the covering of a stupa - a monument that was originally built over Buddhist religions. The square base with the dome above was decorated with reliefs in the niche with the transcendent Buddha Amitabhe in meditation posture, holding a bed/bowl in his hands as an attribute of his dignity. East India, 10th-11th century, stone.

Stupa fragment. The fragment was part of the covering of a stupa - a monument that was originally built over Buddhist religions. The square base with the dome above was decorated with reliefs in the niche with the transcendent Buddha Amitabhe in meditation posture, holding a bed/bowl in his hands as an attribute of his dignity. East India, 10th-11th century, stone.

Buddha Altar. The Buddha figure in meditation gesture on the altar was consecrated by Abbot Samut Theesuka and other monks from Wat Dhammaniwasa (Eschweiler) on 27 August 2022 – as part of a thanksgiving ceremony for the couple Dr. Alfred and Doris Jung.

Buddha Altar. The Buddha figure in meditation gesture on the altar was consecrated by Abbot Samut Theesuka and other monks from Wat Dhammaniwasa (Eschweiler) on 27 August 2022 – as part of a thanksgiving ceremony for the couple Dr. Alfred and Doris Jung.

A film project ‘Phra Malai - Journey through Heaven and Hell’ by studio drei and Jie Lu 2022. Phra Malai - A Journey through Heaven and Hell: The Thai manuscript tells the story of the scholar Phra Malai, who had reached the stage of freedom from suffering on the Buddhist path of healing. He possessed extraordinary powers and could fly to heaven as well as go to hell. He passed on these experiences in his sermons as guidance for a moral life. At the end of the 18th / beginning of the 19th century, the legend was one of the most popular subjects and was recited especially at funeral ceremonies and weddings. The popularity. of the legend is reflected in the artistically varied realization over the centuries - thus elaborate illustrations and special writings adorn the manuscript.

A film project ‘Phra Malai - Journey through Heaven and Hell’ by studio drei and Jie Lu 2022. Phra Malai - A Journey through Heaven and Hell: The Thai manuscript tells the story of the scholar Phra Malai, who had reached the stage of freedom from suffering on the Buddhist path of healing. He possessed extraordinary powers and could fly to heaven as well as go to hell. He passed on these experiences in his sermons as guidance for a moral life. At the end of the 18th / beginning of the 19th century, the legend was one of the most popular subjects and was recited especially at funeral ceremonies and weddings. The popularity. of the legend is reflected in the artistically varied realization over the centuries - thus elaborate illustrations and special writings adorn the manuscript.

The Thai manuscript: Phra Malai - A Journey through Heaven and Hell, which was the basis for the film project above.

The Thai manuscript: Phra Malai - A Journey through Heaven and Hell, which was the basis for the film project above.

Painting by Somnuk Permthongkhum, Thailand, 1973, silk, color. The folkloristic depiction shows the life and hustle and bustle along the river that once characterized Bangkok. Several scenes deal with silk production. Boats bring their goods to the houses built on the waterfront with surrounding terraces. In the upper part of the picture, women are filling a Buddhist monk’s alms bowl with rice from magnificent lacquer vessels. Kneeling, a devotee presents him with a lotus bud.

Painting by Somnuk Permthongkhum, Thailand, 1973, silk, color. The folkloristic depiction shows the life and hustle and bustle along the river that once characterized Bangkok. Several scenes deal with silk production. Boats bring their goods to the houses built on the waterfront with surrounding terraces. In the upper part of the picture, women are filling a Buddhist monk’s alms bowl with rice from magnificent lacquer vessels. Kneeling, a devotee presents him with a lotus bud.

Architectural element. The two cheeks of a protruding portal crowning are decorated on both sides with fighters on horses, mythical creatures and elephants. Decorated portals were status symbols of the wealthy merchant families in Chettinad, whose prosperity was based on trading branches in Burma, Malaysia and Indonesia. Chettinad, Tamil Nadu, South India, 19th century Wood.

Architectural element. The two cheeks of a protruding portal crowning are decorated on both sides with fighters on horses, mythical creatures and elephants. Decorated portals were status symbols of the wealthy merchant families in Chettinad, whose prosperity was based on trading branches in Burma, Malaysia and Indonesia. Chettinad, Tamil Nadu, South India, 19th century Wood.

Tile from a temple. It depicts two kneeling adorants next to an honorary umbrella. Tiles of this type arranged in a row recount events from the earlier ‘births’ of Buddha. The as yet undeciphered inscription in the lower field could provide a clue to the depiction. Pagan, Myanmar, 13th century, terracotta, glaze.

Tile from a temple. It depicts two kneeling adorants next to an honorary umbrella. Tiles of this type arranged in a row recount events from the earlier ‘births’ of Buddha. The as yet undeciphered inscription in the lower field could provide a clue to the depiction. Pagan, Myanmar, 13th century, terracotta, glaze.

Adoring monk. The figure shows a monk with his hands raised in worship. His robe covers his left shoulder; over it lies a wide, narrowly folded cloth. Moggallana and Sariputta, the two favorite disciples of Buddha, are usually depicted in this posture and clothing. Thailand, Sukhothai, 14th/15th century, bronze.

Adoring monk. The figure shows a monk with his hands raised in worship. His robe covers his left shoulder; over it lies a wide, narrowly folded cloth. Moggallana and Sariputta, the two favorite disciples of Buddha, are usually depicted in this posture and clothing. Thailand, Sukhothai, 14th/15th century, bronze.

Adorant. The figure of a kneeling man, dressed and adorned like a prince, was intended as architectural ceramics for a roof ridge. His hands are clasped together in reverence. Thailand, 14th/15th century, stoneware.

Adorant. The figure of a kneeling man, dressed and adorned like a prince, was intended as architectural ceramics for a roof ridge. His hands are clasped together in reverence. Thailand, 14th/15th century, stoneware.

Buddha Amitabha. Amitabha is one of the five transcendent Buddhas, who are timeless and always present. He is often depicted sitting in the lotus position with the hand gesture of meditation. Amitabha is associated with the idea of boundless compassion, light and eternal life. He rules over the western paradise of Sukhavati. Believers hope to be reborn there as blissful beings. The historical Buddha Shakyamuni is regarded as the embodiment of Amitabha. Japan, 19th century, bronze.

Buddha Amitabha. Amitabha is one of the five transcendent Buddhas, who are timeless and always present. He is often depicted sitting in the lotus position with the hand gesture of meditation. Amitabha is associated with the idea of boundless compassion, light and eternal life. He rules over the western paradise of Sukhavati. Believers hope to be reborn there as blissful beings. The historical Buddha Shakyamuni is regarded as the embodiment of Amitabha. Japan, 19th century, bronze.

Avatamsaka Sutra. This stone print from a huge stele reproduces the Avatamsaka Sutra, which is said to have been preached by Buddha Shakyamuni after his enlightenment, in the form of a single snake of text in Chinese script. It teaches the fundamental unity and interpenetration of all things: everything is contained in everything else. This text is followed by the Gandavyuha Sutra, which describes the stages experienced by the boy Sudhana, a student of Buddhist teachings, in his search for supreme enlightenment. China, Qianlong-Ãra - 1736-1796, - Color, paper, textile.

Avatamsaka Sutra. This stone print from a huge stele reproduces the Avatamsaka Sutra, which is said to have been preached by Buddha Shakyamuni after his enlightenment, in the form of a single snake of text in Chinese script. It teaches the fundamental unity and interpenetration of all things: everything is contained in everything else. This text is followed by the Gandavyuha Sutra, which describes the stages experienced by the boy Sudhana, a student of Buddhist teachings, in his search for supreme enlightenment. China, Qianlong-Ãra - 1736-1796, - Color, paper, textile.

Lintel. The monster mask in the center represents the demon Kala. It was placed at the entrance to temples to ward off evil. Within the relief, Kala serves as the base for the world protector Vishnu, who descends to earth as the dwarf Vamana. There he reveals himself in all his greatness and, with just three steps, embraces the cosmos, thereby redeeming the world. Complex tendrils unfurl to the right and left, some in the form of snakes, between which God Vishnu rises on his mount, the mythical bird Garuda. Cambodia, Ankor period, 11th century, sandstone. Two lions: The two imposing, strictly frontally aligned lions once flanked the entrance to a temple or palace hall. Thailand, 19th century Wood, lacquer, sealing glass.

Lintel. The monster mask in the center represents the demon Kala. It was placed at the entrance to temples to ward off evil. Within the relief, Kala serves as the base for the world protector Vishnu, who descends to earth as the dwarf Vamana. There he reveals himself in all his greatness and, with just three steps, embraces the cosmos, thereby redeeming the world. Complex tendrils unfurl to the right and left, some in the form of snakes, between which God Vishnu rises on his mount, the mythical bird Garuda. Cambodia, Ankor period, 11th century, sandstone. Two lions: The two imposing, strictly frontally aligned lions once flanked the entrance to a temple or palace hall. Thailand, 19th century Wood, lacquer, sealing glass.

Vishnu on Garuda. While Vishnu is a Hindu god, Garuda is a mythical bird in both Hindu and Buddhist mythology. The sculpture made from a tree trunk is a masterpiece of traditional carving art; only Garuda’s beak is attached. Bali, Indonesia, 19th century, wood, paint.

Vishnu on Garuda. While Vishnu is a Hindu god, Garuda is a mythical bird in both Hindu and Buddhist mythology. The sculpture made from a tree trunk is a masterpiece of traditional carving art; only Garuda’s beak is attached. Bali, Indonesia, 19th century, wood, paint.

Shadow plays Wayang Kulit. On Java there is evidence of these shadow plays with artistically perforated and painted figures made of buffalo hide from the 9th century. For a thousand years they were placed in a ritual context - today their entertainment character is more pronounced. In nocturnal performances the master of the shadow play conjures up past times, the old order of things and the protection of the ancestors. Above all the episodes and characters from the great Indian epic poems Ramayana and Mahabharata are well known and popular among spectators before and behind the screen. Photo installation: Views of a nocturnal shadow play, Surakarta, 1994 and 2005.

Shadow plays Wayang Kulit. On Java there is evidence of these shadow plays with artistically perforated and painted figures made of buffalo hide from the 9th century. For a thousand years they were placed in a ritual context - today their entertainment character is more pronounced. In nocturnal performances the master of the shadow play conjures up past times, the old order of things and the protection of the ancestors. Above all the episodes and characters from the great Indian epic poems Ramayana and Mahabharata are well known and popular among spectators before and behind the screen. Photo installation: Views of a nocturnal shadow play, Surakarta, 1994 and 2005.

Conclusion

While being a hub of Christian and medieval art and culture, Cologne indeed also offers rich opportunities for exploring Buddhist and East Asia art, spanning a wide range of cultures and regions, ancient and modern. For those interested in exploring Buddhist art, both the Museum of East Asian Art and the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum offer rich and varied collections. Each museum, with its unique focus and approach, provides a comprehensive understanding of the breadth and diversity of Buddhist art. Whether you are an art enthusiast, a student of Buddhism, or simply curious about different cultures, I think that these museums are definitely a must for a visit to Cologne.

comments