On the Hellenistic heritage in Christian culture and Buddhist art

What I realize after all my recent museum visits and studies is that long believed differences between different cultures and time are indeed less strong and sharp than I thought or got taught. In school, I learned – in a very simplified summary – that after the fall of the Roman Empire, the world fell into a dark age (which it wasn’t), and only with the Renaissance, the light of culture and art was rekindled. And that between the Greco-Roman culture and the Christian culture of the Middle Ages, there was a deep rift. But the more I research, the more I realize that this is not the case. The Greco-Roman heritage was not lost, but rather transformed and adapted to the new cultural context. Surprisingly, the same is true for the Buddhist art. The so-called Gandhara style was influenced by Hellenistic art and culture. In this post, I’d like to summarize my so-far findings and share my thoughts on this topic.

Statue of the so-called Aphrodite on the Tortoise (Aphrodite Brazzà), clothed, standing, c. 430 - 420 BC, found: Attica? (Greece). The statue is probably a late Hellenistic or early Imperial copy of a Greek original from around 430 - 420 BC. The turtle is a post-antique addition, but it may well correspond to the attribute of the original, as Pausanias and Plutarch mention an Aphrodite Urania in Elis, who placed one foot on a turtle. Altes Museum, Berlin.

Statue of the so-called Aphrodite on the Tortoise (Aphrodite Brazzà), clothed, standing, c. 430 - 420 BC, found: Attica? (Greece). The statue is probably a late Hellenistic or early Imperial copy of a Greek original from around 430 - 420 BC. The turtle is a post-antique addition, but it may well correspond to the attribute of the original, as Pausanias and Plutarch mention an Aphrodite Urania in Elis, who placed one foot on a turtle. Altes Museum, Berlin.

Greco-Roman culture and its evolution

The evolution of Greco-Roman culture is deeply intertwined with the historical narrative of Hellenism. This period, initiated by Alexander the Great’s conquests in the 4th century BC, marked the spread of Greek culture across a vast expanse from the Eastern Mediterranean to parts of Asia. Hellenism represents not just a geographical expansion but also a cultural and philosophical dissemination of Greek ideas and aesthetics.

Map of the empire of Alexander the Great. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Map of the empire of Alexander the Great. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Alexander’s campaigns led to the establishment of Greek cities and colonies far beyond the traditional boundaries of the Greek world. These new territories, often ruled by Greek-speaking elites, became centers where Greek art, literature, philosophy, and political ideas mingled with local traditions. This fusion resulted in a rich, diverse cultural milieu, where classical Greek traditions evolved in unique ways, adapting to various local contexts.

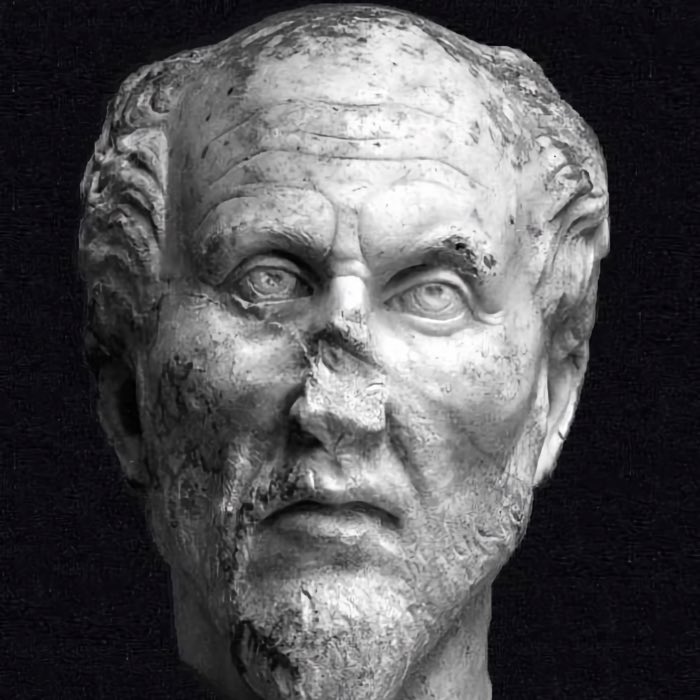

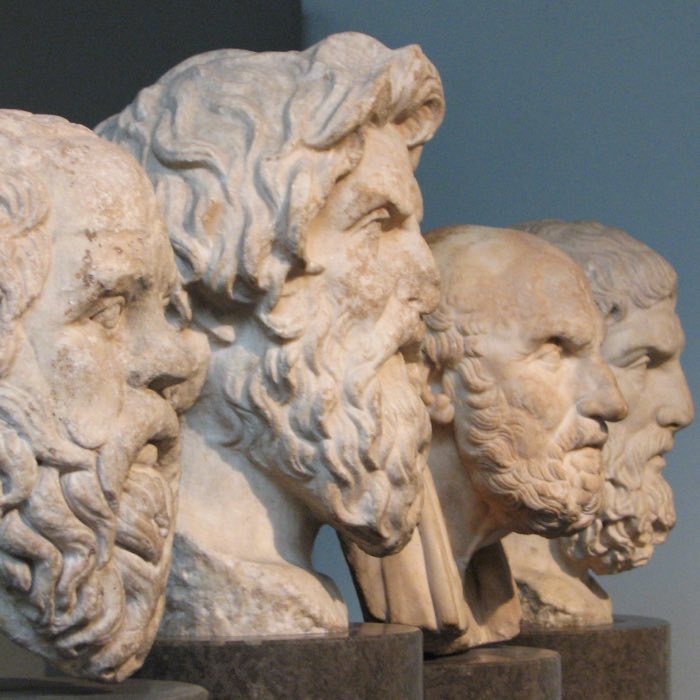

In art and architecture, Hellenism is characterized by an increased emphasis on realism and the exploration of new subjects and styles. The period saw innovations in the portrayal of emotions, movement, and physical details, moving beyond the idealized forms of the classical period. This was also a time when art became more accessible to the public, moving away from being the exclusive domain of gods and rulers.

The Hellenistic influence profoundly shaped Roman culture as Rome’s power expanded into Hellenistic territories. The Romans, initially influenced by the Etruscans, came into direct contact with the Hellenistic world during their conquests. They were greatly impressed by Greek art and philosophy, which they began to assimilate into their own culture. Roman art, initially characterized by practicality and a focus on realism, was significantly transformed by the idealism and naturalism of Greek art. This assimilation was not a mere copying of Greek styles; rather, the Romans adapted and reinterpreted Greek elements, leading to the creation of a distinct Greco-Roman aesthetic.

The Roman Empire and its provinces at the time of its greatest expansion under Emperor Trajan in the years 115-117. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

The Roman Empire and its provinces at the time of its greatest expansion under Emperor Trajan in the years 115-117. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

This Greco-Roman culture, a blend of Roman practicality and Greek idealism, set the foundation for the cultural and artistic developments of the later periods, including the Christian medieval era. The legacy of Hellenism, therefore, is not confined to its historical period but extends far into the future, significantly influencing the course of Western art and culture.

Roman general, 1st century CE, location: Cologne-Marienburg, Römisch-Germanisches Museum, Cologne, Germany. The statue shows a high-ranking military officer with decorated muscle armor, a general’s armband around his waist and a heavy military coat. It is not clear whether it depicts an emperor, a general or possibly even Mars, the god of war.

Roman general, 1st century CE, location: Cologne-Marienburg, Römisch-Germanisches Museum, Cologne, Germany. The statue shows a high-ranking military officer with decorated muscle armor, a general’s armband around his waist and a heavy military coat. It is not clear whether it depicts an emperor, a general or possibly even Mars, the god of war.

Hellenistic Influence in Christian medieval art

The impact of Greco-Roman culture on medieval Christian art is not limited to visual aesthetics; it extends deeply into the philosophical and theological underpinnings of Christianity during the Middle Ages. This influence is evident in the way Christian thinkers and artists integrated Hellenistic philosophical concepts into Christian doctrine, and how this integration manifested in the art of the period.

Philosophical and theological synthesis

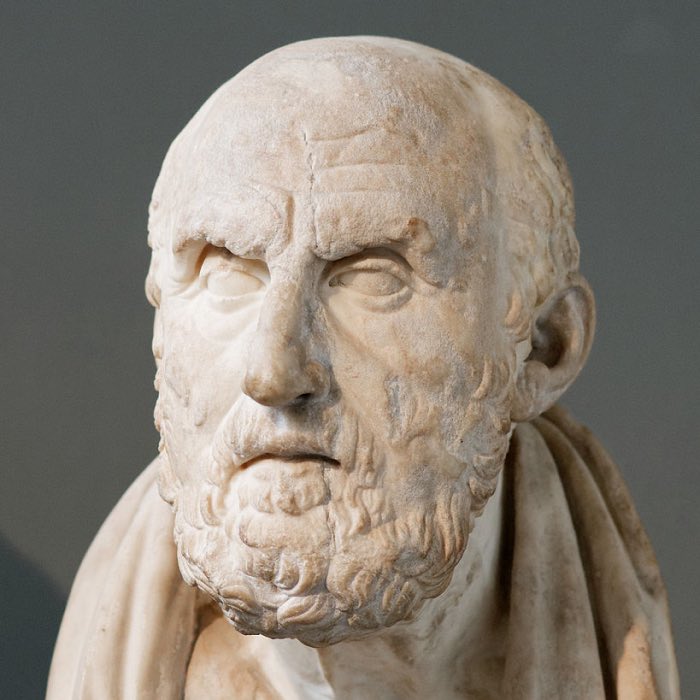

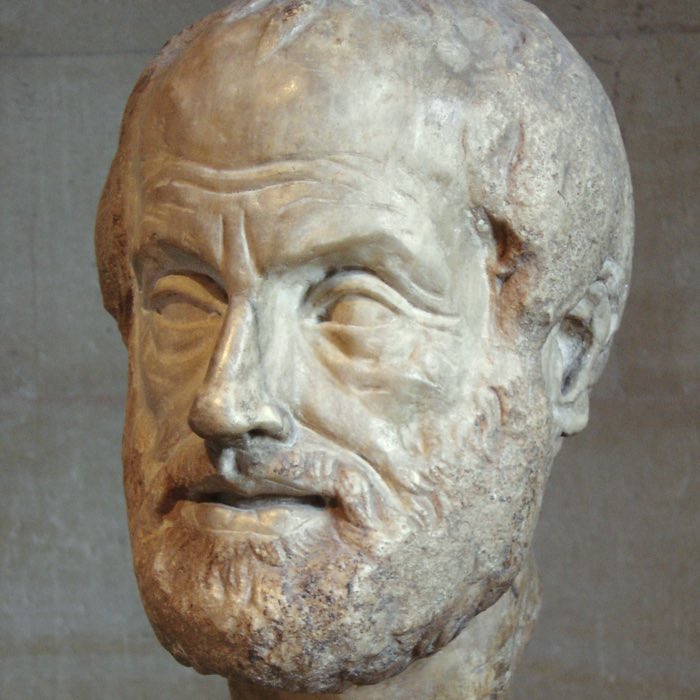

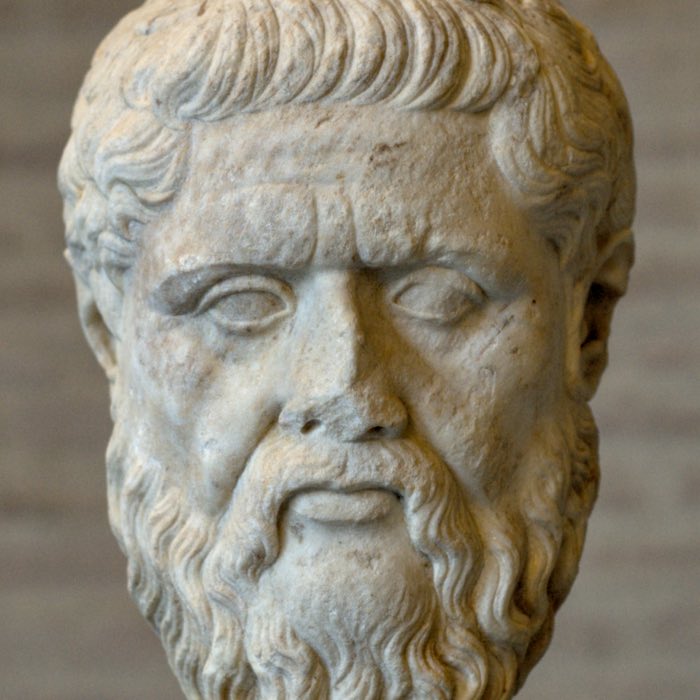

The early Christian Church was in a unique position, emerging in a world where Hellenistic philosophy was deeply entrenched. Church Fathers, such as Augustine of Hippo and Thomas Aquinas, engaged extensively with Greco-Roman thought. Augustine’s philosophical writings, for instance, show the influence of Plato and Neoplatonism, emphasizing ideals such as the immateriality of the soul and the existence of an ultimate, unchanging truth. Aquinas later integrated Aristotelian philosophy, particularly his empirical approach and ideas about the natural world, into Christian theology. This intellectual fusion created a foundation for medieval Christian philosophy, where faith and reason were often seen as complementary rather than contradictory.

Artistic manifestations of philosophical ideas

In medieval Christian art, this synthesis of Hellenistic philosophy and Christian theology is subtly woven into the iconography and themes. The emphasis on narrative scenes in Christian art, particularly in illuminated manuscripts, stained glass windows, or stone reliefs, reflects not only a continuation of Roman artistic traditions but also the Christian emphasis on storytelling as a means of illustrating moral and theological lessons. This narrative approach can be traced back to the Hellenistic tradition of depicting mythological and historical scenes, which was adapted to convey Christian stories and parables.

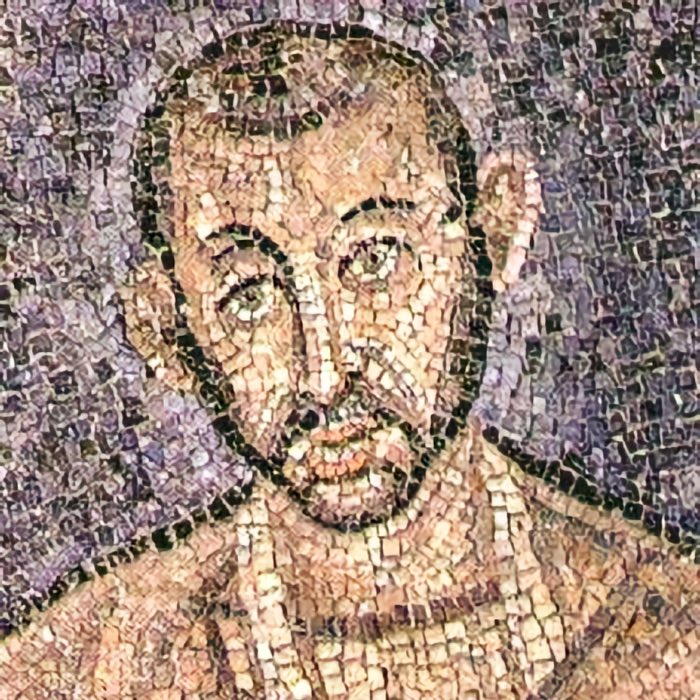

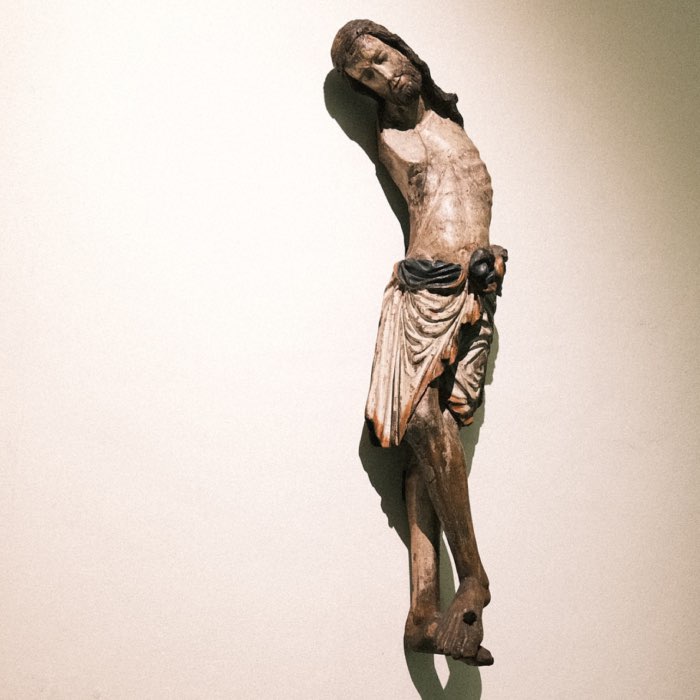

The portrayal of Christ, saints, and biblical figures often drew on the idealized forms of Greco-Roman art, symbolizing the perfection of divine and moral virtues. The serene expressions and harmonious proportions found in late medieval Christian sculptures and paintings echo the Hellenistic ideals of beauty and perfection, which were now reinterpreted to reflect the spiritual perfection and divinity of Christian figures.

Fragment of a robed figure, late 10th cent. / 1st third 11th cent., shelly limestone, Cologne, St. Pantaleon. After the burial of Archbishop Bruno in the Church of St. Pantaleon in 965, the Benedictine abbey he had recently founded underwent extensive reconstruction, during which the remains of St. Maurinus were discovered. Some twenty years later, a gift from Empress Theophanu also brought the relics of St. Albinus to the Church of St. Pantaleon. The Albinus altar, near which the empress was buried in 991, occupied a central position in the western annex of the church. Perhaps as early as the end of the 10th century, but no later than the 1020s, the westwork was renovated. The facade of the build-ing was decorated with an elaborate, monumental sculptural programme, of which three special fragments are on display here. The figure of Christ occupied a central position in the three-storey structure. The larger-than-life head of his sculpture has survived. The fragment of a beardless head probably belongs to an angel. The fragment of the life-size robed figure of a male saint could have been one of the church’s patrons or even Albinus. See more from this series in this post. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Fragment of a robed figure, late 10th cent. / 1st third 11th cent., shelly limestone, Cologne, St. Pantaleon. After the burial of Archbishop Bruno in the Church of St. Pantaleon in 965, the Benedictine abbey he had recently founded underwent extensive reconstruction, during which the remains of St. Maurinus were discovered. Some twenty years later, a gift from Empress Theophanu also brought the relics of St. Albinus to the Church of St. Pantaleon. The Albinus altar, near which the empress was buried in 991, occupied a central position in the western annex of the church. Perhaps as early as the end of the 10th century, but no later than the 1020s, the westwork was renovated. The facade of the build-ing was decorated with an elaborate, monumental sculptural programme, of which three special fragments are on display here. The figure of Christ occupied a central position in the three-storey structure. The larger-than-life head of his sculpture has survived. The fragment of a beardless head probably belongs to an angel. The fragment of the life-size robed figure of a male saint could have been one of the church’s patrons or even Albinus. See more from this series in this post. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Mary with the Christ Child, Cologne, c. 1270, Chalky sandstone. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Mary with the Christ Child, Cologne, c. 1270, Chalky sandstone. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Column chapter “Monthly images”, Padua, mid-13th c., Veronese marble. The double capital depicts the activities during the first six months of the year. See more from this series in this post. Bode Museum, Berlin.

Column chapter “Monthly images”, Padua, mid-13th c., Veronese marble. The double capital depicts the activities during the first six months of the year. See more from this series in this post. Bode Museum, Berlin.

Apostle James the Lesser (?), Pacio Bertini gen. Pacio da Firenze, verifiable 1st half 14th c. Naples, c. 1340 (?), marble. The left hand originally held a book, the right probably the whaler pole. See more from this series in this post. Bode Museum, Berlin.

Apostle James the Lesser (?), Pacio Bertini gen. Pacio da Firenze, verifiable 1st half 14th c. Naples, c. 1340 (?), marble. The left hand originally held a book, the right probably the whaler pole. See more from this series in this post. Bode Museum, Berlin.

Architectural continuity and transformation

In architecture, the influence of Roman structural design is evident in the basilica layout, which became the standard for Christian churches. This architectural form was adapted to suit the liturgical needs and symbolic purposes of Christian worship. The Roman basilica, originally used for public gatherings and judicial purposes, was transformed into a space that symbolized the Christian universe, with its nave representing the earthly realm and the sanctuary symbolizing the heavenly.

Moral and ethical influences

Furthermore, Greco-Roman virtues such as temperance, justice, and courage were assimilated into Christian ethics, often depicted in art through allegorical figures or scenes from the lives of saints who embodied these virtues. This integration illustrates how Christian art became a medium not only for religious instruction but also for the moral and ethical education of the faithful, a concept deeply rooted in the philosophical traditions of ancient Greece and Rome.

An influence beyond aesthetics

In summary, the influence of Hellenistic culture on medieval Christian art and thought was profound and multifaceted. It was not a mere continuation of artistic styles, but a deep and complex integration of philosophical, theological, and ethical concepts. Of course, this synthesis was not without tensions and conflicts, as Christian theologians grappled with the perceived pagan elements in Greco-Roman culture. Also, lots of the ancient knowledge was lost or forgotten due to harsh censorship and active destruction of pagan temples and libraries. However, the synthesis of Greco-Roman and Christian ideas laid the foundation for the intellectual and artistic achievements of the Middle Ages. It helped shape a unique Christian worldview that was visually expressed in the art of the Middle Ages, demonstrating the enduring and transformative impact of Greco-Roman culture on the Christian tradition.

Greco-Roman echoes in Buddhist art: The Gandhara style

Christian art and culture were not the only beneficiaries of Hellenistic influence. The influence of Hellenistic art extended far beyond the boundaries of the Alexander’s and the Roman Empire, reaching as far as the Buddhist regions of Gandhara (in present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan). The Gandhara style of Buddhist art, which flourished from the 1st century BCE to the 5th century CE, is a striking example of cross-cultural artistic synthesis.

Historical context and cultural interchange

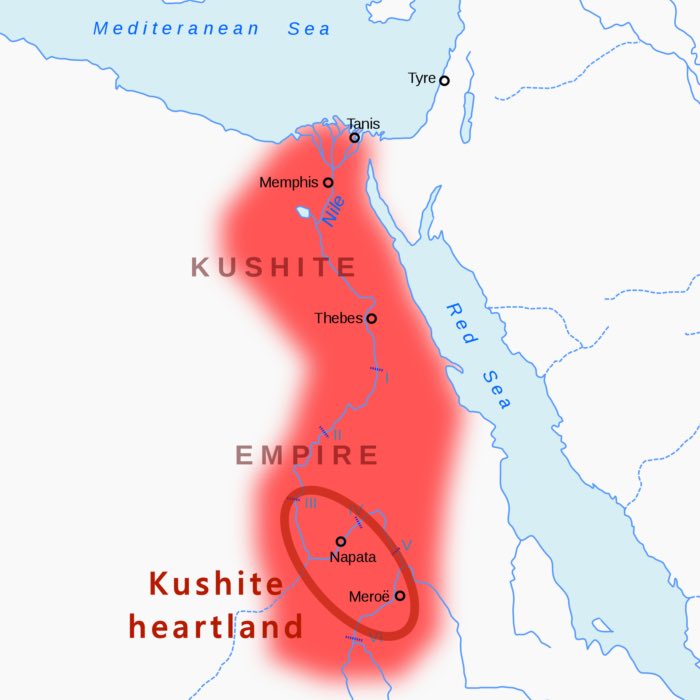

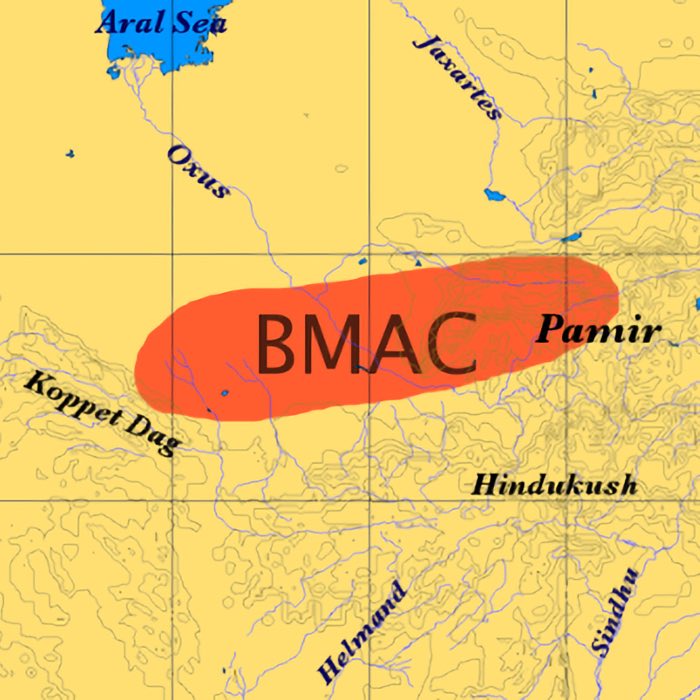

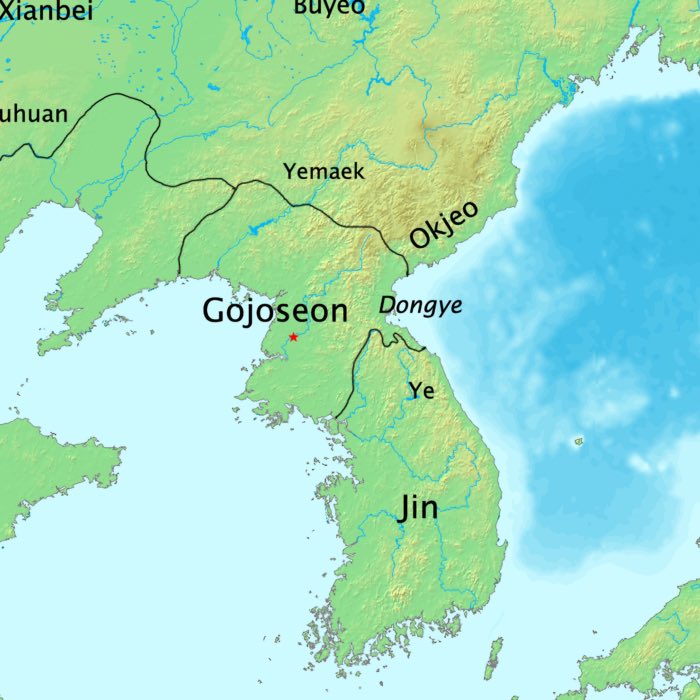

The establishment of the Gandhara region as a cultural hub began with Alexander the Great’s incursions, which introduced Greek artistic and cultural elements to the area. Following Alexander’s campaigns, the region saw a succession of rulers, including the Mauryans, Indo-Greeks, Scythians, Parthians, and Kushans, each contributing to the region’s rich cultural tapestry. The Indo-Greek Kingdoms, in particular, played a pivotal role in the fusion of Hellenistic and Buddhist traditions. This period of cultural synthesis was marked by a significant exchange of ideas, as Greek artistic techniques and Buddhist religious concepts influenced each other.

Kingdoms and cities of ancient Buddhism, with Gandhara located in the northwest of this region, during the time of the Buddha (c. 500 BC). The Mahajanapadas were sixteen most powerful and vast kingdoms and republics around the lifetime of Siddhartha Gautama (563–483 BCE), located mainly across the fertile Indo-Gangetic plains, there were also a number of smaller kingdoms stretching the length and breadth of Ancient India. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Kingdoms and cities of ancient Buddhism, with Gandhara located in the northwest of this region, during the time of the Buddha (c. 500 BC). The Mahajanapadas were sixteen most powerful and vast kingdoms and republics around the lifetime of Siddhartha Gautama (563–483 BCE), located mainly across the fertile Indo-Gangetic plains, there were also a number of smaller kingdoms stretching the length and breadth of Ancient India. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Territory of the Indo-Greeks circa 150 BC. The Indo-Greek Kingdom was one of the Hellenistic kingdoms covering various parts of the northwest regions of the Indian subcontinent (mainly modern Afghanistan and Pakistan, including the Gandhara region) during the last two centuries BC. It emerged following the collapse of the Maurya Empire and the invasion of the Greco-Bactrians into India, starting around 180 BC. The Indo-Greek Kingdom was established by Demetrius I of Bactria (reigned c. 200–180 BC) and was ruled by a succession of more than thirty Greek kings over the next two centuries (with Menander I being the most well known amongst them). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Territory of the Indo-Greeks circa 150 BC. The Indo-Greek Kingdom was one of the Hellenistic kingdoms covering various parts of the northwest regions of the Indian subcontinent (mainly modern Afghanistan and Pakistan, including the Gandhara region) during the last two centuries BC. It emerged following the collapse of the Maurya Empire and the invasion of the Greco-Bactrians into India, starting around 180 BC. The Indo-Greek Kingdom was established by Demetrius I of Bactria (reigned c. 200–180 BC) and was ruled by a succession of more than thirty Greek kings over the next two centuries (with Menander I being the most well known amongst them). Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Extent of Buddhism and trade routes (red dashed lines) in the 1st century CE, showing the trade interconnections between Buddhist regions (including the Gandhara region), the Greco-Roman world, the Arabian Peninsular, and Northern Africa. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Extent of Buddhism and trade routes (red dashed lines) in the 1st century CE, showing the trade interconnections between Buddhist regions (including the Gandhara region), the Greco-Roman world, the Arabian Peninsular, and Northern Africa. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Artistic characteristics and innovations

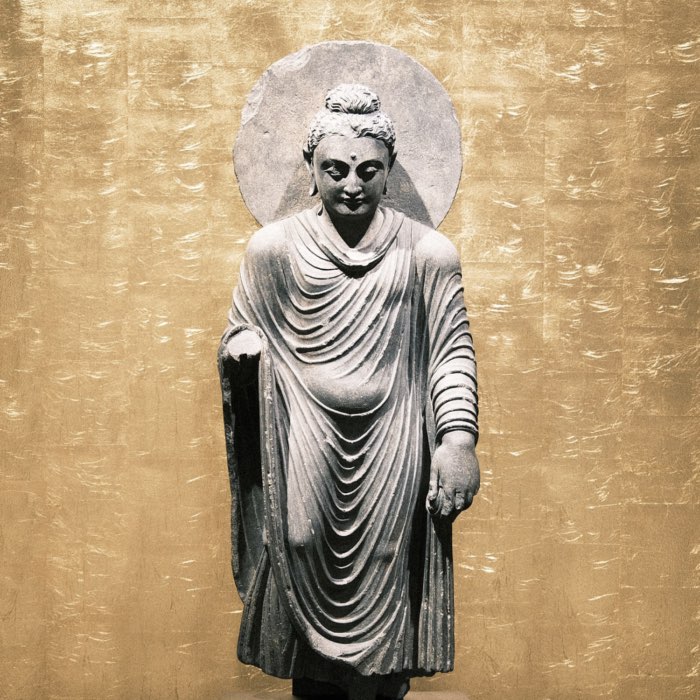

In Gandhara art, the depiction of the Buddha underwent a revolutionary transformation. Prior to Hellenistic influence, Buddhist art was aniconic; the Buddha was represented through symbols rather than human form. The Gandhara style introduced the anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha, combining Hellenistic sculptural techniques with Buddhist iconography. This synthesis is evident in the statues of the Buddha, which exhibit a striking resemblance to Greek and Roman sculptural traditions:

- Anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha

- Prior to Hellenistic influence, Buddhist art was predominantly aniconic; the Buddha was represented through symbols like the lotus, the wheel, or the Bodhi tree. The introduction of the anthropomorphic image of the Buddha in Gandhara art, influenced by Greek and Roman sculptural traditions, was a significant shift. This change in representation can be seen as a response to the Greco-Roman cultural context, where gods and divine figures were commonly depicted in human form. This adaptation made Buddhist teachings more accessible and relatable to people accustomed to Greco-Roman religious imagery.

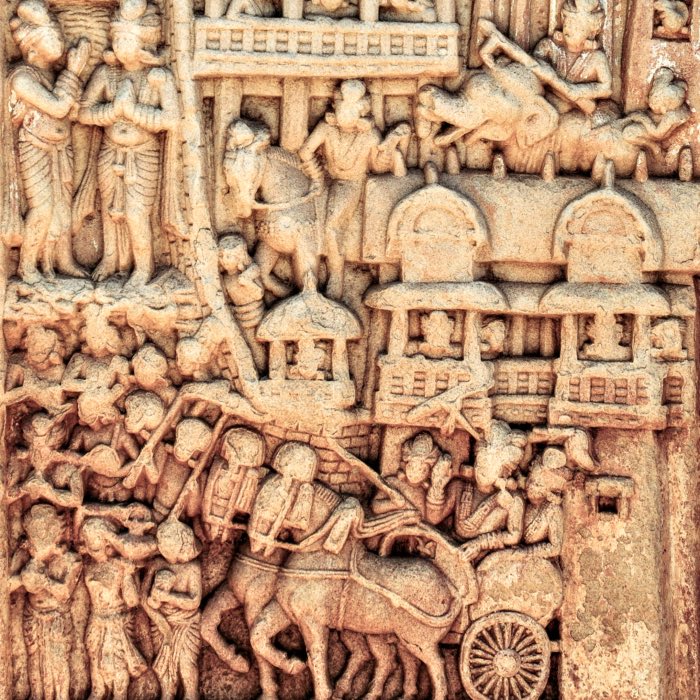

- Narrative reliefs and storytelling

- The narrative reliefs in Gandhara art, depicting scenes from the Buddha’s life and Jataka tales, show a clear Hellenistic influence in their composition and realism. These reliefs served as visual sermons that communicated Buddhist teachings in a format that was familiar to a Hellenistic audience. The detailed depiction of human emotions and physical surroundings in these reliefs made the Buddhist stories more engaging and comprehensible to people from different cultural backgrounds.

- Iconographic fusion

- The iconography of the Buddha in Gandhara art incorporated Hellenistic elements such as the wavy hair and draped robes, along with traditional Buddhist symbols like the ushnisha (the cranial protuberance on Buddha’s head) and urna (the dot between Buddha’s eyes). This fusion symbolizes a blending of Greek philosophical ideals with Buddhist concepts. For instance, the serene expression and idealized form of the Buddha statues echo the Greek pursuit of ideal beauty and perfection, while also embodying the Buddhist ideals of enlightenment and spiritual tranquility.

- Architectural elements

- The influence extends to architectural elements, with the adoption of Corinthian columns and Greco-Roman decorative motifs in Buddhist stupas and monasteries. These structures often featured intricate friezes and coffered ceilings, blending Hellenistic architectural styles with Buddhist symbolism.

The Gandhara style represents more than an artistic phenomenon; it signifies a profound intercultural dialogue. The fusion of Hellenistic and Buddhist elements in Gandhara art reflects a broader process of cultural and religious exchange. It demonstrates how Buddhist philosophy and iconography adapted and evolved through interaction with other cultures, leading to a more universal representation of Buddhist themes that could resonate with a diverse audience along the Silk Road. Moreover, the presence of Buddhist monasteries and stupas in Gandhara, adorned with Hellenistic art, attracted pilgrims and travelers from various regions. This exposure helped disseminate Buddhist teachings across Central and East Asia, integrating them with diverse cultural and religious traditions. For instance, the stylistic features and iconographic motifs of Gandhara art influenced the development of Buddhist art in China, Korea, and Japan, marking it as a significant point of transmission for Buddhist iconography and philosophy from the Indian subcontinent to East Asia.

Adoration of a stupa, Central India, Sanchi, 1st cent., sandstone, exhibited at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin. This is an example of aniconic Buddhist art, where the Buddha is not depicted in human form but symbolically represented by a stupa. A stupa is a mound housing Buddhist relics, which are hidden within its massive hill-shaped structure. It is worshipped by walking clockwise around it. Here, two men with turbans have put their hands together in the Indian gesture of worship. Heavenly beings bring flower offerings. Other reliefs from the same series can be found in this post.

Adoration of a stupa, Central India, Sanchi, 1st cent., sandstone, exhibited at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin. This is an example of aniconic Buddhist art, where the Buddha is not depicted in human form but symbolically represented by a stupa. A stupa is a mound housing Buddhist relics, which are hidden within its massive hill-shaped structure. It is worshipped by walking clockwise around it. Here, two men with turbans have put their hands together in the Indian gesture of worship. Heavenly beings bring flower offerings. Other reliefs from the same series can be found in this post.

Mara’s assault, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd - 3rd c., schist, exhibited at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin. The Buddha is sitting in meditation under the Tree of Enlightenment. He practices the quiet observation of the breath. Suddenly, wild figures besiege him. They embody noise, fear, aggression and passion. They are the troops of Mara, a symbolic figure in Buddhism for the entanglement in suffering. But Buddha preserves his equanimity. He frees himself from the power of Mara through meditation. More reliefs from the same series can be found in this post.

Mara’s assault, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd - 3rd c., schist, exhibited at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin. The Buddha is sitting in meditation under the Tree of Enlightenment. He practices the quiet observation of the breath. Suddenly, wild figures besiege him. They embody noise, fear, aggression and passion. They are the troops of Mara, a symbolic figure in Buddhism for the entanglement in suffering. But Buddha preserves his equanimity. He frees himself from the power of Mara through meditation. More reliefs from the same series can be found in this post.

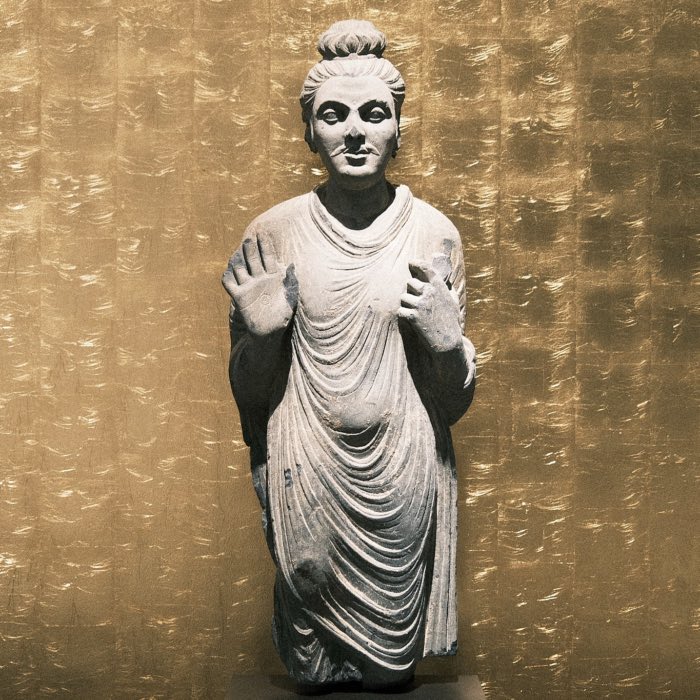

Standing Buddha, Pakistan, Gandhara, Takht-i-Bahi, 2nd -3rd c., schist, exhibited at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin. A deep sense of peace pervades the face of this standing Buddha. His eyes are lowered, and the facial features are completely smooth, free from any passion. The left hand hangs down, clasping a small loop of his robe, and the right arm is raised. The missing hand was probably raised in the gesture of protection (abhaya mudra). See more from this series in this post.

Standing Buddha, Pakistan, Gandhara, Takht-i-Bahi, 2nd -3rd c., schist, exhibited at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin. A deep sense of peace pervades the face of this standing Buddha. His eyes are lowered, and the facial features are completely smooth, free from any passion. The left hand hangs down, clasping a small loop of his robe, and the right arm is raised. The missing hand was probably raised in the gesture of protection (abhaya mudra). See more from this series in this post.

Synthesis or appropriation?

While the influence of Hellenistic culture on Gandhara Buddhist art is widely acknowledged, some scholars caution against oversimplifying this relationship. They argue that while Hellenistic influence is evident, it is essential to recognize the agency and creativity of local artists who selectively adopted and adapted these influences. This perspective suggests a more dynamic and reciprocal exchange, where Gandhara art is not merely a derivative of Greek art but a sophisticated synthesis that reflects a complex interplay of local and foreign elements.

A testament to the interconnectedness of cultures

In my opinion, the Gandhara style and art stand as a testament to the dynamic exchange between Hellenistic and Buddhist cultures. It exemplifies how artistic forms and religious ideas can intermingle, leading to innovative expressions of spiritual and aesthetic ideals. This style not only enriched Buddhist art but also contributed to the broader narrative of cultural interaction and exchange in the ancient world, highlighting the interconnectedness of civilizations and the shared heritage of humanity.

Conclusion

The enduring legacy of Greco-Roman culture in the Christian and Buddhist art is a testament to the dynamic nature of artistic expression and cultural exchange. In the Christian context, the Greco-Roman heritage was not merely preserved; it was transformed, giving rise to new artistic languages that expressed the spiritual and philosophical ideals of the medieval Christian world. Similarly, in the Buddhist art of Gandhara, the fusion of Hellenistic and local elements resulted in a unique artistic tradition that profoundly influenced the development of Buddhist iconography across Asia.

These cross-cultural echoes highlight the interconnectedness of human cultures and the capacity of art to transcend geographical and cultural boundaries. The Greco-Roman artistic legacy, in its journey through time and space, serves as a vivid reminder of the shared heritage of humanity and the enduring power of art to bridge diverse worlds.

Understanding the nuanced interplay of Greco-Roman and medieval Christian art and Buddhist art not only enriches our appreciation of historical art forms but also offers valuable insights for contemporary cultural discourse. While in the past cultural exchange has often been viewed through the lens of dominance or appropriation, the history of these artistic traditions reminds us of the potential for respectful and enriching cultural synthesis. It challenges us to look beyond simplistic narratives of cultural purity and to embrace the complex, often beautiful results of cultural intermingling. This perspective encourages a more inclusive and holistic view of art history and cultural heritage, one that acknowledges the multifaceted influences that shape artistic expression and human creativity.

References and further reading

- William Woodthorpe Tarn, Hellenistic Civilization, 1961, Penguin Books Ltd, ISBN: 9780452008151

- John Boardman, Greek Sculpture: The Late Classical Period and Sculpture in Colonies and Overseas, 1995, Thames & Hudson, ISBN: 9780500202852

- Kenneth Clark, Civilisation: A Personal View, 2005, John Murray Publishers, pages 265, ISBN: 9780719568442

- Diarmaid MacCulloch, Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years, 2010, Penguin, ISBN: 9781101189993

- Heather Elgood, Hinduism and the Religious Arts, 2000, A&C Black, ISBN: 9780304707393

- Denise Patry, Donna K. Strahan, & Lawrence Becker, Wisdom Embodied: Chinese Buddhist and Daoist Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010, Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, ISBN: 9780300155211

- Kurt Behrendt, How to Read Buddhist Art, 2019, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN: 9781588396730

- David Jongeward, Buddhist Art of Gandhara: In the Ashmolean Museum, 2019, Ashmolean Museum, ISBN-13: 978-1910807224

- John Guy & Vincent Tournier, Tree and Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India, 2023, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN: 9781588396938

- John Boardman, The Greeks in Asia, 2015, National Geographic Books, ISBN: 9780500252130

- Richard Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road: Premodern Patterns of Globalization, 2010, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN: 978023062125

- Lawrence S. Cunningham, John J. Reich, & Lois Fichner-Rathus, Culture and Values: A Survey of the Western Humanities, 2014, Cengage Learning, ISBN: 9781285449326

- Christopher I. Beckwith, Greek Buddha: Pyrrho’s Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia, 2015, Princeton University Press, ISBN 10: 0691166447

- Thomas C. McEvilley, The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies, 2001, Allworth, ISBN: 978-1581152036

comments