Lares and the evolution of household deities in Europe

During my visit to the Roman-Germanic Museum in Cologne, I stumbled upon intriguing small deity figures, which piqued my curiosity. Upon further research, I discovered they were representations of Roman Lares, ancient household deities. This discovery led me to draw some parallels with later religious practices, including those found in Eastern traditions.

Function of the Lares

In ancient Rome, Lares were revered as guardian deities, playing a crucial role in daily life. They were believed to protect the home and ensure the prosperity and well-being of the family. Unlike the major gods of Roman mythology such as the Capitoline Triad of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva) who were worshipped in temples and public ceremonies, Lares were more intimately connected with the everyday lives of ordinary people. They were not just protectors but also witnesses to the daily routines and rituals of Roman households.

Lares, 2nd/3rd century CE, found at Comelle-sous-Beuvray (bronze hoard).

Lares, 2nd/3rd century CE, found at Comelle-sous-Beuvray (bronze hoard).

Central to the veneration of Lares was the lararium, a sacred space within the Roman home. Typically, the lararium was an altar or shrine where the family would offer prayers, sacrifices, and offerings to the Lares. The lararium often held small statues or images of the Lares, along with other familial and protective deities like the Penates and Genius. This space was not merely a religious focal point but also a symbol of the family’s identity and continuity, as the composition of the deities set up was unique to each household.

Lararium in the house of the Vettier in Pompeii. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (CC BY-SA 2.5).

Lararium in the house of the Vettier in Pompeii. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (CC BY-SA 2.5).

Interestingly, the lararium was strategically placed so it could “watch over” and thus “protect” the entire house. This concept parallels the principles of an ancient Roman Feng Shui, where the positioning of sacred elements in living spaces was believed to influence the well-being and fortune of the inhabitants. The lararium’s placement was not only a religious statement but also a reflection of the ancient Roman understanding of space, esoteric symbolism, and protection.

Examples

Here are some of my favorite pieces from the museum’s collection. All shown photographs are taken by me and the background information is based on the museum’s descriptions.

Lares, 2nd/3rd century CE, found at Comelle-sous-Beuvray (bronze hoard).

Lares, 2nd/3rd century CE, found at Comelle-sous-Beuvray (bronze hoard).

Lares, 2nd/3rd century CE, found at Comelle-sous-Beuvray (bronze hoard).

Lares, 2nd/3rd century CE, found at Comelle-sous-Beuvray (bronze hoard).

Lares, 2nd/3rd century CE, found at Comelle-sous-Beuvray (bronze hoard).

Lares, 2nd/3rd century CE, found at Comelle-sous-Beuvray (bronze hoard).

Lares, 2nd/3rd century CE, found at Comelle-sous-Beuvray (bronze hoard).

Lares, 2nd/3rd century CE, found at Comelle-sous-Beuvray (bronze hoard).

Lares, 2nd/3rd century CE, found at Comelle-sous-Beuvray (bronze hoard).

Lares, 2nd/3rd century CE, found at Comelle-sous-Beuvray (bronze hoard).

Comparison with Christian house altars

The tradition of household deities and altars did not end with the Roman era. As Christianity spread, the concept of household worship evolved, integrating elements of earlier practices. Christian house altars, which emerged later, bear a resemblance to the lararia. These altars often feature icons, statues, or images of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and various saints, serving a similar purpose of daily devotion and protection. The transition from Lares to Christian figures illustrates how new religious beliefs can absorb and reinterpret existing traditions, creating a continuity of domestic spirituality.

Christian home altar, Lisbon, museu de Artes Decorativas. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Christian home altar, Lisbon, museu de Artes Decorativas. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Lares were not confined to homes. In the ancient Roman Empire, they were also venerated at crossroads, where small shrines or altars were erected. This practice finds a parallel in the Christian tradition of placing statues of the Virgin Mary, Jesus, and saints at street corners, house walls, and roadside crosses. The Christian adoption and adaptation of these sites demonstrate a strategic integration of local customs, facilitating the transition from pagan to Christian worship.

Lararium in Pompeji. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (Copyright free use).

Lararium in Pompeji. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (Copyright free use).

Altar site on a wayside in the form of a Christian cross (today without a statue).

Altar site on a wayside in the form of a Christian cross (today without a statue).

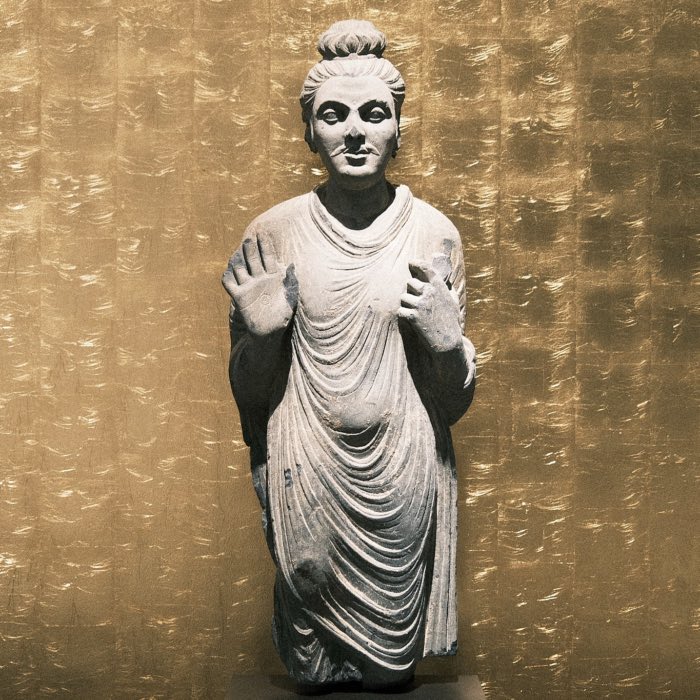

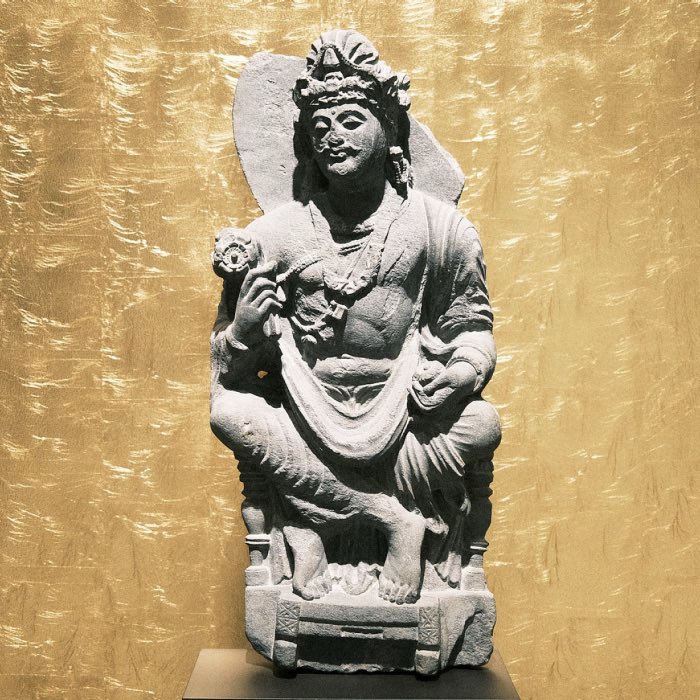

Parallels with Asian Buddhist statues

The small statues of Lares bear a striking resemblance to the miniature Buddhist brass and bronze statues found across Asia. These Buddhist statues, often crafted with meticulous detail, serve as physical embodiments of spiritual beings such as Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and celestial guardians.

Both the Lares of ancient Rome and the Buddhist statues of Asia play integral roles in domestic and communal religious practices. They are placed in homes, temples, and public spaces to invoke blessings, ensure prosperity, and offer protection. This shared function highlights a universal human impulse to symbolize and invoke divine presence in tangible forms, regardless of cultural context.

The similarities between Roman Lares and Buddhist statues suggest a commonality in how different cultures express and nurture spiritual beliefs through physical representations. These parallels reflect a fundamental aspect of human spirituality: the desire to connect with and seek guidance from the divine in everyday life, using tangible symbols as conduits for faith and devotion.

Conclusion

The Roman Lares, with their enduring presence from ancient households to modern museums, offer a fascinating glimpse into the continuity and evolution of spiritual practices. Their legacy, from the lararium in ancient Roman homes to the Christian house altars and the Buddhist statues of Asia, reveals a shared human inclination towards creating sacred spaces for protection, worship, and connection with the divine. These practices, evolving through time and across cultures, highlight the adaptability and resilience of spiritual traditions. The Lares, initially small figures in Roman homes, thus symbolize a broader narrative of religious and cultural synthesis, reflecting humanity’s ongoing quest to find comfort and meaning in the divine, whether in the bustling streets of ancient Rome or in the quiet corners of modern homes.

References and further reading

- Website of the Roman-Germanic Museum in Cologneꜛ

- Marcus Trier, Friederike Naumann-Steckner, 14 CE - Römische Herrschaft am Rhein, 2014, Wienand, ISBN: 9783868322262

- Hugo Borger, Helga Schmidt-Glassner, Das Römisch-Germanische Museum Köln, 1977, Callwey, ISBN: 9783766703842

comments