Roman legacy of glass art in Cologne

Cologne not only has a rich Roman heritage, but also a (perhaps) lesser-known history of glassmaking. Archaeological finds in the city have revealed a rich heritage of glass art, encompassing from everything drinking vessels to jewelry and decorative objects. And the Roman-Germanic Museum in Cologneꜛ (RGM) houses a significant collection of these artifacts. Here are some of my favorite pieces that I have photographed during my last visits. The background information is based on the museum’s descriptions.

Glass in early Cologne, 1st century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Glass in early Cologne, 1st century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Dawn of glass art in Roman Cologne

Cologne, known in Roman times as Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium (CCAA), was indeed a significant urban center in the Roman Empire. The city’s strategic location along the Rhine made it a hub for cultural and commercial exchange. Among the many artistic crafts that flourished in this milieu was glassmaking, an art that the Romans did not invent but significantly refined and popularized across their empire.

Roman glassware was not merely functional; it was a symbol of status and wealth. The techniques used in Cologne, such as blowing, casting, and cutting, were advanced for their time, resulting in pieces that were both delicate and intricate. The glassblowers of Cologne were adept at creating a range of products, from transparent drinking vessels to colored glass beads, each item reflecting a high level of craftsmanship.

The beauty of Roman glass lies in its variety and the skill evident in its production. The glassmakers of Cologne mastered techniques like millefiori, where rods of differently colored glass were fused and sliced to create flower-like patterns. Another technique, cameo glass, involved fusing two layers of glass of different colors and carving away parts of the upper layer to create a design in relief, much like the famous Portland Vase.

One of the most common and admired techniques was glassblowing, which allowed for the creation of delicate and uniformly thin vessels, a feat not possible with earlier methods. This innovation led to an explosion in the variety of shapes and sizes of glassware, from fine drinking cups to large storage jars.

Fragility and rarity

The very nature of glass – its fragility – has meant that fewer pieces have survived compared to more durable materials like stone or metal. This rarity makes the pieces displayed in museums such as the RGM all the more precious. Each surviving piece provides a unique window into the daily life, culture, and aesthetics of Roman Cologne.

With the decline of the Roman Empire and the onset of the Middle Ages and the rise of Germanic kingdoms, many of the sophisticated techniques developed by Roman glassmakers were lost or fell out of fashion. The rise of Christianity also influenced this decline. As the new religion spread, its initial indifference and later opposition to opulence and luxury affected the production and use of fine glassware. The focus shifted towards more austere and functional forms of art and craftsmanship.

Examples

Here are some of my favorite pieces from the museum’s collection.

Emergence of glass art in ancient Cologne

From its earliest days, Cologne, a burgeoning metropolis on the Rhine, became a hub for glass items originating from Italy, Gaul, and the eastern regions of the empire. The city saw an influx of luxurious glass tableware, notable for its vivid colors and a variety of shapes. These pieces ranged from translucent to opaque and were crafted with or without embellishments. Local glass workshops demonstrated remarkable creativity in producing an array of bottles and flasks. These were designed for holding ointments, oils, perfumes, makeup, and other valuable substances, showcasing the artisans’ limitless imagination in their craft.

Glass in early Cologne, 1st century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Glass in early Cologne, 1st century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Glass in early Cologne, 1st century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Glass in early Cologne, 1st century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Glass in early Cologne, 1st century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Glass in early Cologne, 1st century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Glass in early Cologne, 1st century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Glass in early Cologne, 1st century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Glass in early Cologne, 1st century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Glass in early Cologne, 1st century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

“Kölner Schnörkel”

Glass artists were skilled in adorning glass vessels with intricate designs, employing hot glass threads to create patterns of waves, leaves, and scrolls with a freehand technique that demonstrated remarkable fluidity and ease. They also used colored glass threads to fashion the distinctive “Kölner Schnörkel” (Cologne scrollwork). This unique design started with a flat, arched ‘Z’, extended into various wavy lines towards the right, and culminated in an open volute. This scrollwork became a significant hallmark of Cologne’s glass art, as recognizable and emblematic in its time as some of today’s well-known corporate logos.

Cologne scrollwork, “Kölner Schnörkel”, c. CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Cologne scrollwork, “Kölner Schnörkel”, c. CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Cologne scrollwork, “Kölner Schnörkel”, c. CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Cologne scrollwork, “Kölner Schnörkel”, c. CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Cologne scrollwork, “Kölner Schnörkel”, c. CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Cologne scrollwork, “Kölner Schnörkel”, c. CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Cologne scrollwork, “Kölner Schnörkel”, c. CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Cologne scrollwork, “Kölner Schnörkel”, c. CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Unique creations

The ingenuity and expertise of the glassblowers of ancient Cologne seemed boundless. Nature, with its array of animals and fruits, often provided a rich source of inspiration for their creations. Intricately crafted shells, octopuses, dolphins, and fish adorned goblets and cups, bringing an element of the marine world into everyday items. Perfume containers were whimsically shaped into glass birds, pigs, and even dates, each piece a testament to the glassblower’s artistry. Glass sandals, another novel creation, were used to hold precious essences. Among these unique items, the cup with colorful, snail-like overlays stands out as a singular masterpiece to this day. The drinking horn, meanwhile, represented a glass interpretation of traditional Germanic drinking customs. These remarkable vessels, each a work of art, were often bestowed upon the deceased, accompanying them as treasured possessions into the afterlife.

Unique creations, Individual pieces, 1st-4th century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Unique creations, Individual pieces, 1st-4th century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Unique creations, 1st-4th century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Unique creations, 1st-4th century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Unique creations, 1st-4th century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Unique creations, 1st-4th century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Unique creations, 1st-4th century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Unique creations, 1st-4th century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Unique creations, 1st-4th century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Unique creations, 1st-4th century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Individual pieces, 1st-4th century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Individual pieces, 1st-4th century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Free-blown glass

In the process of free-blown glassmaking, the initial step involves gathering a mass of molten glass at the end of a glassblower’s pipe. This is expertly blown into a spherical shape, forming the foundational structure for free-blown glass vessels. This sphere serves as a versatile canvas, offering the glassblower - both in ancient times and today - limitless possibilities for creative expression. Through a series of skilled manipulations such as curving, indenting, bulging, twisting, expanding, or narrowing, the glass is transformed. Techniques like cutting, melting, interlocking, and flattening further diversify the range of shapes and designs achievable. Moreover, this malleable glass can be fashioned into a wide array of figures, showcasing the remarkable versatility and artistry inherent in the craft of free-blown glass.

Free-blown glass, 1st - 4th century CE, found in: Cologne, various sites.

Free-blown glass, 1st - 4th century CE, found in: Cologne, various sites.

Free-blown glass, 1st - 4th century CE, found in: Cologne, various sites.

Free-blown glass, 1st - 4th century CE, found in: Cologne, various sites.

Mass-produced glassware

In Roman times, the need for uniform, standardized containers was crucial for the commercial transport and sale of various products. Despite its fragility, glass was favored for being taste-neutral, an important quality for storage. The advent of glassblowing techniques facilitated the relatively easy production of glass containers with consistent shapes and sizes. Depending on the specific type of vessel required, these containers were often composed of multiple individual parts, each crafted using molds. This process allowed for the efficient mass production of glassware, meeting the demands of commerce and trade in the Roman era.

Uniform mass-produced ware, 1st - 3rd century CE, found in: Cologne, various sites.

Uniform mass-produced ware, 1st - 3rd century CE, found in: Cologne, various sites.

Uniform mass-produced ware, 1st - 3rd century CE, found in: Cologne, various sites.

Uniform mass-produced ware, 1st - 3rd century CE, found in: Cologne, various sites.

Uniform mass-produced ware, 1st - 3rd century CE, found in: Cologne, various sites.

Uniform mass-produced ware, 1st - 3rd century CE, found in: Cologne, various sites.

Uniform mass-produced ware, 1st - 3rd century CE, found in: Cologne, various sites.

Uniform mass-produced ware, 1st - 3rd century CE, found in: Cologne, various sites.

Faceted and incised glassware

A notable method of embellishing drinkware, including jugs, jars, cups, and bowls, involved various intricate cutting techniques. The surfaces of these vessels, typically crafted from colorless or slightly yellowish-green glass, were adorned with a rich array of decorative cuts. These embellishments included full coverage with faceted and spherical cuts, as well as scored and frosted ornamental bands, adding a layer of sophistication and beauty to each piece. A particularly distinguished example of this craftsmanship is the small Lynkeus beaker, which stands out due to its exceptional figure cut, showcasing the high level of skill and artistry prevalent among Roman glassmakers in Cologne.

Faceted and incised, 3rd-4th century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Faceted and incised, 3rd-4th century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Faceted and incised, 3rd-4th century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

Faceted and incised, 3rd-4th century CE, found in Cologne, various sites.

A unique treasure: The diatret glass

The exquisite design of a particular glass goblet in Roman Cologne showcases a remarkable fusion of skill and creativity. This goblet features a clear inner cup, seamlessly integrated with a multicolored lattice network. Encircling the rim, a Greek inscription in purple letters elegantly states: “ΠIE ZHCAIC KAΛΩC AEI” - translating to “Drink, live beautifully forever.” Below this inscription lies a collar of yellow glass, leading to a green basket-like structure with four rows of round mesh. The mesh’s junction points are delicately embellished with small bows, adding to the goblet’s intricate beauty. The cup and its mesh network are connected by exceedingly slender bars, a testament to the glassmaker’s precision and skill.

This unique style is known as ‘diatret,’ a term derived from the Greek word meaning ‘pierced.’ This special design, with its intricate pierced appearance, represents the zenith of the glassmaker’s art in Roman times. The diatret glass goblet not only serves as a functional vessel but also stands as an enduring symbol of the extraordinary craftsmanship and aesthetic sensibilities of ancient Roman glass artists.

Diatret glass, 1st half of the 4th century CE, found in Cologne-Braunsfeld.

Diatret glass, 1st half of the 4th century CE, found in Cologne-Braunsfeld.

The legendary Achilles: A treasured burial find

A remarkable burial discovery from the western burial ground of ancient Cologne unveils a glimpse into the opulent funerary customs of the time. Among the array of rich gifts unearthed, several items stand out for their unique craftsmanship and cultural significance. Notably, a necklace, a gagat (jet) finger ring, a silver knife, and a knife with a handle shaped like a reclining dog, crafted from amber, draw particular attention for their exquisite artistry.

However, the centerpiece of this burial trove is an extraordinary glass goblet, which is not just a vessel but a canvas for storytelling. This goblet is adorned with vibrant enamel colors, vividly portraying a scene from the myth of the Greek hero Achilles. The depiction of Achilles, a figure renowned for his strength and valor in Greek mythology, on this goblet is a testament to the cultural interconnections of the ancient world. It also highlights the exceptional skill of Roman glassmakers in Cologne, who were adept not only in the crafting of glass but also in the art of painting, bringing legendary tales to life through their work.

This goblet, with its intricate depiction of Achilles, serves as a significant archaeological find. It provides valuable insights into the artistic preferences and cultural influences present in Roman Cologne, illustrating how mythological narratives were celebrated and immortalized in everyday objects.

The legendary Achilles in Roman Cologne, 1st half of the 3rd century CE, found: Cologne, Richard-Wagner-Straße.

The legendary Achilles in Roman Cologne, 1st half of the 3rd century CE, found: Cologne, Richard-Wagner-Straße.

Transition to Frankish Glass

As the Germanic kingdoms rose to prominence, there was a noticeable shift in the glassmaking landscape of Cologne. The once-flourishing art of glassmaking experienced a decline, with the city’s storied tradition persisting albeit on a reduced scale and with simpler techniques. The glass vessels crafted during the early Middle Ages, while still rooted in the legacy of Roman glassmaking expertise, underwent adaptations to align with Frankish customs and preferences.

A notable innovation of this era was the introduction of baseless glasses, commonly known as tumblers. These drinking cups had a unique design feature: they could only be set down when completely empty, as their rounded bottoms prevented them from standing upright when filled. This design not only reflected the practical aspects of Frankish dining and drinking customs but also added a distinctive cultural touch to the glassware of the period.

Despite the changes in craftsmanship, Cologne maintained its status as a significant hub for glass processing during the early Middle Ages. This enduring importance is evidenced by the frequent discovery of glass items as grave goods in Frankish burial sites, mirroring a similar practice from the Roman era. These findings highlight the continuous, albeit evolving, role of glass in the cultural and social practices of the region, bridging the Roman and Frankish periods in Cologne’s rich history.

Frankish glass, 5th to 7th century CE, found in Cologne-Müngersdorf and -Junkersdorf.

Frankish glass, 5th to 7th century CE, found in Cologne-Müngersdorf and -Junkersdorf.

Frankish glass, 5th to 7th century CE, found in Cologne-Müngersdorf and -Junkersdorf.

Frankish glass, 5th to 7th century CE, found in Cologne-Müngersdorf and -Junkersdorf.

Frankish glass, 5th to 7th century CE, found in Cologne-Müngersdorf and -Junkersdorf.

Frankish glass, 5th to 7th century CE, found in Cologne-Müngersdorf and -Junkersdorf.

Frankish glass, 5th to 7th century CE, found in Cologne-Müngersdorf and -Junkersdorf.

Frankish glass, 5th to 7th century CE, found in Cologne-Müngersdorf and -Junkersdorf.

Cologne stoneware of the late Middle Ages

A comeback of artistic expression in everyday objects was witnessed in Cologne during the late Middle Ages. In the middle of the 15th century, Cologne’s master potters began to produce stoneware. Although the sophisticated craftsmanship of the Roman period was never fully replicated, Cologne stoneware developed a distinctive and recognizable trademark within the Rhineland.

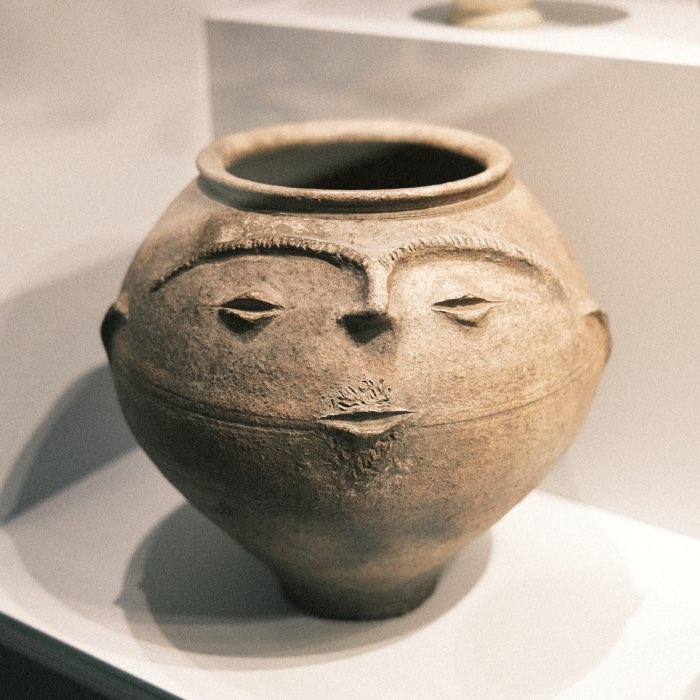

The range of shapes produced by the Cologne workshops was rather sparse compared to the products of the pottery centers in the surrounding area. Bulbous jugs with a spherical body are characteristic of Cologne utility ceramics made of stoneware. However, Cologne stoneware became famous for its so-called Bartmann jug, a pear-shaped drinking and serving jug with a single bearded male face mask on the neck and shoulder of the vessel. Based on 15th century jugs with primitive-looking carved facial contours, this special form of jug was developed in Cologne from around 1500 onwards and can be found in almost all Rhenish pottery centers in the 16th century. The Bartmann jug later became a typical product of Frechen stoneware production, where it continued to be made well into the 18th century.

Bartmann jug, Cologne 1530/65. For a long time, historians assumed that the expression ‘Alaaf’, used during Cologne Carnival, originated from the 18th century. This Bartmann jug proves that the word was used as a cheer or toast as early as 1550. In this context, the term means ‘Nothing is better than a good drink’. The jug was found during excavations on Streitzeuggasse Street. Exhibited at the Cologne City Museum.

Bartmann jug, Cologne 1530/65. For a long time, historians assumed that the expression ‘Alaaf’, used during Cologne Carnival, originated from the 18th century. This Bartmann jug proves that the word was used as a cheer or toast as early as 1550. In this context, the term means ‘Nothing is better than a good drink’. The jug was found during excavations on Streitzeuggasse Street. Exhibited at the Cologne City Museum.

Bartmannskrug, stoneware, Frechen, salt glaze, Germany, c. 1600. Ceramics were also traded from Europe to East Asia. A Rhenish Bartmann jug purchased before 1909 in Japan is an impressive piece of evidence. They were called hige tokkuri (‘beard jugs’) and even copied by local potters. Exhibited in the Museum for East Asian Art in Cologne.

Bartmannskrug, stoneware, Frechen, salt glaze, Germany, c. 1600. Ceramics were also traded from Europe to East Asia. A Rhenish Bartmann jug purchased before 1909 in Japan is an impressive piece of evidence. They were called hige tokkuri (‘beard jugs’) and even copied by local potters. Exhibited in the Museum for East Asian Art in Cologne.

Conclusion

Today, the remnants of Cologne’s glassmaking tradition are not just archaeological artifacts; they are testimonies to a once-thriving art form that flourished in the heart of the Roman Empire. The delicate glass vessels, beads, and ornaments that have survived the ravages of time are windows into the past, offering insights into the craftsmanship, aesthetics, and cultural practices of ancient Cologne.

The history of Cologne glassmaking also reflects the broader history of the city itself. The transition from Roman to Frankish glassware mirrors the historical shifts that occurred in the region, from the decline of the Roman Empire to the rise of the Germanic kingdoms. The decline and primitivization of once skilled craftsmanship is a prime example of the impact that the transition to Christianity and the concomitant decline of Roman civilization had on a well-developed culture and people’s everyday lives.

By studying and preserving these fragile treasures, we keep alive the city’s links to its Roman past, thereby maintaining an essential part of Cologne’s historical identity.

References and further reading

- Friederike Naumann-Steckner, Marcus Trier, Zerbrechlicher Luxus - Köln - ein Zentrum antiker Glaskunst, 2016, Schnell & Steiner, ISBN: 9783795431440

- Marcus Trier, Friederike Naumann-Steckner, 14 CE - Römische Herrschaft am Rhein, 2014, Wienand, ISBN: 9783868322262

- E. M. Stern, Römisches, byzantinisches und frühmittelalterliches Glas. Sammlung Ernesto Wolf. 10 v. Chr. - 700 n. Chr, 2001, Hatje Cantz, ISBN: 9783775790413

- Donald B. Harden, Hansgerd Hellenkemper, Kenneth Painter, David Whitehouse, Glas der Caesaren, 1988, Olivetti

- Website of the Roman-Germanic Museum in Cologneꜛ

- Ingeborg Unger, Kölner und Frechener Steinzeug der Renaissance. Die Bestände des Kölnischen Stadtmuseums, 2007, Hrsg. von Werner Schäfke. Publikationen des Kölnischen Stadtmuseums Band 8. 549 Seiten. Verlag Kölnisches Stadtmuseum, ISBN 978-3-940042-01-9

- Karl Göbels, Rheinisches Töpferhandwerk. Gezeigt am Beispiel der Frechener Kannen-, Düppen- und Pfeifenbäcker, 1971, Rheinland-Verlag, Köln

- Wikipedia article on Cologne stonewareꜛ

comments