Silent narrators: Medieval wood sculptures

The European Middle Ages was an era of profound artistic and spiritual exploration. During my recent visits to medieval churches and museums, I was impressed by the remarkable craftsmanship and artistic expression of wooden sculptures in particular. These sculptures, primarily driven by religious themes, offer a unique window into the medieval mind, its craftsmanship, and its spiritual quests. Here are some shots of my favorite wood sculptures that I captured during my last visits to the Museum Schnütgen and other places in Cologne.

Adoration of the Magi (detail), Workshop of Arnt Beeldesnider, с. 1480-90, OakSee further description below.

Adoration of the Magi (detail), Workshop of Arnt Beeldesnider, с. 1480-90, OakSee further description below.

Medieval wood sculptures

Wood sculptures in the Middle Ages emerged as significant art forms. Initially, they were primarily used in church decor, serving as altarpieces, statues of saints, and parts of crucifixes. The primary patrons of these sculptures were the Church, monasteries, and the nobility. Their intentions were predominantly religious, aiming to educate the illiterate, inspire devotion, and represent biblical narratives and saints. However, these sculptures also served as symbols of power and prestige for their patrons.

Medieval wood sculptors were highly skilled craftsmen. Their work involved selecting suitable wood, mastering carving techniques, and often applying gold leaf or paint. The level of detail in these sculptures, from the delicate drapery folds to the nuanced expressions, reflects a high degree of technical proficiency and artistic sensibility.

The artistry of medieval wood sculptures also lay in the meticulous selection of materials and the mastery of carving techniques. Sculptors typically chose durable woods like oak or lime wood, valued for their workability and fine grain. Using an array of tools such as chisels, mallets, and knives, they skillfully transformed these timbers into detailed religious figures and scenes. The process often involved intricate detailing, with some sculptures adorned with polychrome, gilding, or both, to add vibrancy and life to the finished piece. This combination of material knowledge and technical skill was essential in bringing these spiritual visions to tangible reality. Despite the dominant religious themes, many medieval wood sculptors managed to imprint their individual style onto their works. This individuality is seen in the unique interpretation of subjects, the specific style of carving, and the emotional expressiveness imbued in the sculptures.

Notable masters

Masters like Tilman Riemenschneider, Meister Arnt von Kalkar, and Tilman von Köln were renowned for their exceptional skills and artistic innovations. Riemenschneider, for instance, is celebrated for his expressive, detailed, and unpolished wood sculptures, which allowed the natural grain of the wood to enhance the figures’ realism and emotional depth.

Tilman Riemenschneider (c. 1460-1531)

Tilman Riemenschneider, one of the most celebrated German sculptors of the late Middle Ages, is renowned for his innovative approach to wood carving. Operating primarily in Würzburg, Riemenschneider’s work is distinguished by its intricate detail and expressive emotion. His figures often exhibit a profound sense of realism and introspection, a departure from the more rigid and formal depictions typical of earlier medieval art. Notable works like the Altarpiece of the Holy Blood (c. 1501-1505) in Rothenburg ob der Tauber and the limewood sculptures at the Münnerstadt Altarpiece showcase his skill in capturing human emotion and his mastery of drapery. Riemenschneider’s work is also significant for its lack of polychrome, allowing the natural beauty of the wood to contribute to the expressiveness of his sculptures.

Tilman Riemenschneider, Heiligenstadt workshop, c. 1460-1531 Würzburg. Godfather with the Suffering Christ of the Passion (Throne of Mercy), c. 1510, limewood, old version. The dove of the Holy Spirit is missing today. Bode Museum, Berlin.

Tilman Riemenschneider, Heiligenstadt workshop, c. 1460-1531 Würzburg. Godfather with the Suffering Christ of the Passion (Throne of Mercy), c. 1510, limewood, old version. The dove of the Holy Spirit is missing today. Bode Museum, Berlin.

Tilman Riemenschneider, Heiligenstadt, c. 1460 - 153 Würzbur. St. Anne and her three husbands, c. 1505/10, limewood. Bode Museum, Berlin.

Tilman Riemenschneider, Heiligenstadt, c. 1460 - 153 Würzbur. St. Anne and her three husbands, c. 1505/10, limewood. Bode Museum, Berlin.

Meister Arnt von Kalkar (active c. 1460-1492)

Meister Arnt, also known as Arnt Beeldsnijder (Arnt the Carver), was a pivotal figure in the transition from the late Gothic to the Renaissance style in the Lower Rhineland. His work is characterized by a remarkable attention to detail and a dynamic representation of figures. Arnt’s sculptures often feature elaborate clothing and intricate facial expressions, capturing both the spiritual and earthly qualities of his subjects. His altarpieces, such as the one in the church of Kalkar, from which he likely took his name, demonstrate a mastery of narrative storytelling through wood carving. His ability to imbue static wood with a sense of movement and life marks him as a significant contributor to the evolution of sculptural art in the late medieval period.

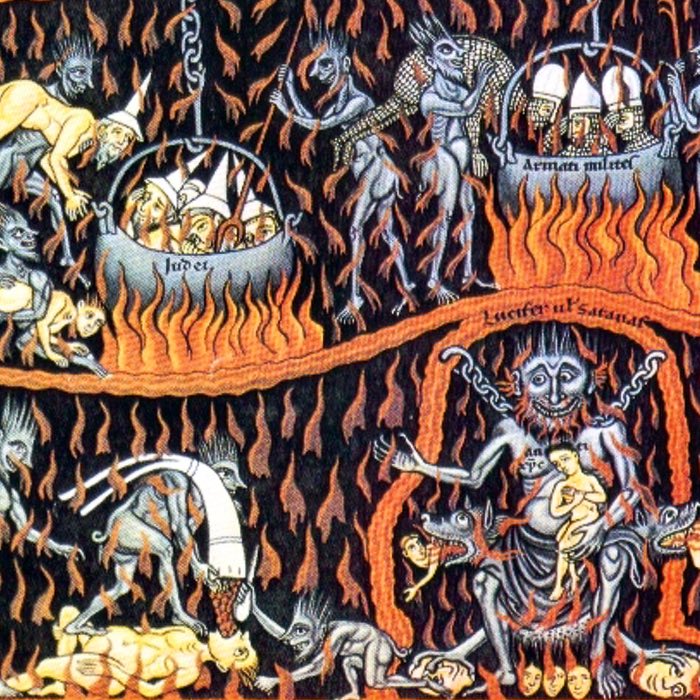

Shrine with scenes of the Passion, predella of an altarpiece Kalkar, c. 1530-1540, Oak. The huge wooden shrine with its numerous figures and scenes is just one part of an originally much larger work of art. It served as a substructure (predella) for a large altar reredos, which could also have wings attached to the sides with further figures or paintings. The different folding of the pairs of wings on certain feast days and holidays resulted in several display sides for the viewer. During the almost 100-year heyday of the giant reredos from the middle of the 15th century onwards, it was not uncommon for panoramas of the entire history of salvation to be created. This Passion shrine shows three important scenes after the crucifixion with great narrative joy. The deep background offers enough space for the depiction of simultaneous events. While the body of Christ is being taken down from the cross in the background on the left, in the foreground we see Mary, the Mother of God, slumped in grief, supported by her favorite disciple John and comforted by two women. All of the figures are striking for the detailed, meticulous design of their clothing, which corresponds to the fashion of the early 16th century. The contemporary hairstyles and headdresses also point to a transfer of the biblical events to the time when the painting was created. This also applies to the subsequent scenes of the Entombment and Resurrection of Christ, where the carver’s delight in storytelling is particularly evident in the depiction of the grave guards. While one guard leans against the sarcophagus and sleeps, another fills his gun with new gunpowder. It was not uncommon for these monumental altarpieces to be donated to churches by wealthy private individuals or professional groups (guilds, guilds). Generous donations were intended to secure the salvation of souls and spare them from the damnation of hell. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Shrine with scenes of the Passion, predella of an altarpiece Kalkar, c. 1530-1540, Oak. The huge wooden shrine with its numerous figures and scenes is just one part of an originally much larger work of art. It served as a substructure (predella) for a large altar reredos, which could also have wings attached to the sides with further figures or paintings. The different folding of the pairs of wings on certain feast days and holidays resulted in several display sides for the viewer. During the almost 100-year heyday of the giant reredos from the middle of the 15th century onwards, it was not uncommon for panoramas of the entire history of salvation to be created. This Passion shrine shows three important scenes after the crucifixion with great narrative joy. The deep background offers enough space for the depiction of simultaneous events. While the body of Christ is being taken down from the cross in the background on the left, in the foreground we see Mary, the Mother of God, slumped in grief, supported by her favorite disciple John and comforted by two women. All of the figures are striking for the detailed, meticulous design of their clothing, which corresponds to the fashion of the early 16th century. The contemporary hairstyles and headdresses also point to a transfer of the biblical events to the time when the painting was created. This also applies to the subsequent scenes of the Entombment and Resurrection of Christ, where the carver’s delight in storytelling is particularly evident in the depiction of the grave guards. While one guard leans against the sarcophagus and sleeps, another fills his gun with new gunpowder. It was not uncommon for these monumental altarpieces to be donated to churches by wealthy private individuals or professional groups (guilds, guilds). Generous donations were intended to secure the salvation of souls and spare them from the damnation of hell. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Adoration of the Magi, Workshop of Arnt Beeldesnider, с. 1480-90, Oak, additions in hardwood, visible polychromy 19th cent. over traces of earlier layers. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne. The multi-layered, figure-rich picture is carved from a huge block of oak, in which everything has been given its place with imaginative attention to detail and great skill. You can see the little page handing the cup to the black king and almost stumbling, as well as the adventurous figures of the entourage with their horses and camels, which seem to come from the depths of the landscape. At the very front, the various phases of movement of the kings paying homage to the Christ Child sweep in a large arc from the right to the calm figure of Joseph on the left edge of the picture. In the ruined stable of Bethlehem, which according to legend was built on the ruins of King David’s palace, you can see battlements and the remains of a tower. As a sign of the new dawn, angels are covering the stable roof with new straw. Master Arnt incorporated many models from the great Dutch painters, from Jan van Eyck to Rogier van der Weyden and Hans Memling, into his composition and became one of the most influential sculptors in the rich artistic landscape of the Lower Rhine.

Adoration of the Magi, Workshop of Arnt Beeldesnider, с. 1480-90, Oak, additions in hardwood, visible polychromy 19th cent. over traces of earlier layers. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne. The multi-layered, figure-rich picture is carved from a huge block of oak, in which everything has been given its place with imaginative attention to detail and great skill. You can see the little page handing the cup to the black king and almost stumbling, as well as the adventurous figures of the entourage with their horses and camels, which seem to come from the depths of the landscape. At the very front, the various phases of movement of the kings paying homage to the Christ Child sweep in a large arc from the right to the calm figure of Joseph on the left edge of the picture. In the ruined stable of Bethlehem, which according to legend was built on the ruins of King David’s palace, you can see battlements and the remains of a tower. As a sign of the new dawn, angels are covering the stable roof with new straw. Master Arnt incorporated many models from the great Dutch painters, from Jan van Eyck to Rogier van der Weyden and Hans Memling, into his composition and became one of the most influential sculptors in the rich artistic landscape of the Lower Rhine.

Tilman von Köln (active late 14th century)

Tilman von Köln, active in the late 14th century, was a prominent sculptor in the Rhineland, contributing significantly to the Gothic style of the region. While less is known about his life compared to Riemenschneider and Meister Arnt, his work is highly regarded for its elegance and emotional depth. His sculptures are noted for their refined craftsmanship and the serene, yet expressive, faces of the figures. A hallmark of his style is the delicate treatment of the figures’ garments, which seem to flow and ripple realistically. Tilman von Köln’s contribution to the Gothic tradition is seen as a bridge between the earlier medieval styles and the burgeoning Renaissance, reflecting a deep understanding of human anatomy and a keen eye for detail that prefigures the changes in European art.

Statue of St. Christopher in Cologne Cathedral, Master Tilman of Cologne, around 1469, tuff stone. Even though this statue was not made of wood, it is representative for Meister Tilman’s style. St. Christopher statues from medieval times were usually placed at the entrance to churches or gates. This also applies to this statue, as the pilgrimage route through the unfinished Cologne Cathedral, which was closed off from the nave by a partition wall, began at the south portal and led the faithful through the choir aisle to the Shrine of the Epiphany and then out again to the north portal. The statue was the first sculpture of a saint in the cathedral that a pilgrim encountered on entering. Even today, on certain occasions, such as the cathedral pilgrimage, pilgrims enter the cathedral through the south portal, which is normally closed. Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Statue of St. Christopher in Cologne Cathedral, Master Tilman of Cologne, around 1469, tuff stone. Even though this statue was not made of wood, it is representative for Meister Tilman’s style. St. Christopher statues from medieval times were usually placed at the entrance to churches or gates. This also applies to this statue, as the pilgrimage route through the unfinished Cologne Cathedral, which was closed off from the nave by a partition wall, began at the south portal and led the faithful through the choir aisle to the Shrine of the Epiphany and then out again to the north portal. The statue was the first sculpture of a saint in the cathedral that a pilgrim encountered on entering. Even today, on certain occasions, such as the cathedral pilgrimage, pilgrims enter the cathedral through the south portal, which is normally closed. Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

St. Dorothy, Cologne, Master Tilman, c. 1500, Beechwood, polychromy. Due to its excellent condition, this delicate statuette of a saint gives a very accurate impression of its original effect: the coloring and gilding are almost completely original. The delicate figure stands in a slight S-shape on a pedestal carved from the same block, the dress adorned with pressed brocade gathered in small, voluminous folds in front of the body. The second hand holds the saint’s attribute, a basket filled with flowers. A broad gold border accentuates the dress and forms a frame with the likewise gilded open cloak and the matt gold hair, from which the luminous incarnation of the finely worked hands and the lovely face stand out brightly. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

St. Dorothy, Cologne, Master Tilman, c. 1500, Beechwood, polychromy. Due to its excellent condition, this delicate statuette of a saint gives a very accurate impression of its original effect: the coloring and gilding are almost completely original. The delicate figure stands in a slight S-shape on a pedestal carved from the same block, the dress adorned with pressed brocade gathered in small, voluminous folds in front of the body. The second hand holds the saint’s attribute, a basket filled with flowers. A broad gold border accentuates the dress and forms a frame with the likewise gilded open cloak and the matt gold hair, from which the luminous incarnation of the finely worked hands and the lovely face stand out brightly. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

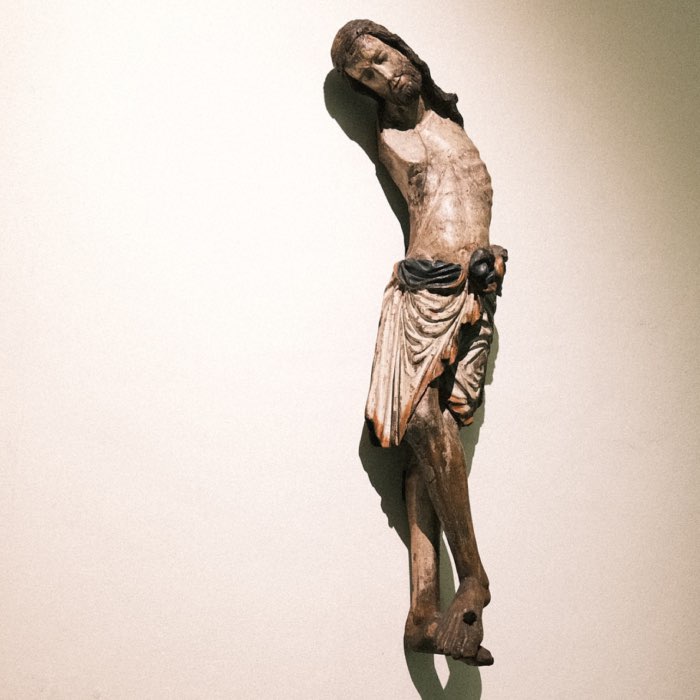

Torso of a Crucifix from a Deposition from the Cross, Cologne (?), c. 1230-1240, Oak, polychromy. The bend of the slender torso to its right indicates that it belongs to a group of the Descent from the Cross with Mary, John, Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, in which the right arm has already been detached from the cross and the left arm is still attached to it. Such scenic groups of figures were particularly common in central Italy and Spain in the decades around 1200, but hardly ever north of the Alps, which is why this work is particularly significant. The figure’s passive pose contrasts with the pleated swirls of the loincloth, which are both decoration and an expression of liveliness. The high quality of the carving is evident in the lively modeling of the chest muscles and in the face, which is finely drawn in clear forms. The expressive first version with the loincloth in blue, red and white and a bluish-white incarnation with a hint of the traces of the flagellation in blue corresponded to this. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Torso of a Crucifix from a Deposition from the Cross, Cologne (?), c. 1230-1240, Oak, polychromy. The bend of the slender torso to its right indicates that it belongs to a group of the Descent from the Cross with Mary, John, Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, in which the right arm has already been detached from the cross and the left arm is still attached to it. Such scenic groups of figures were particularly common in central Italy and Spain in the decades around 1200, but hardly ever north of the Alps, which is why this work is particularly significant. The figure’s passive pose contrasts with the pleated swirls of the loincloth, which are both decoration and an expression of liveliness. The high quality of the carving is evident in the lively modeling of the chest muscles and in the face, which is finely drawn in clear forms. The expressive first version with the loincloth in blue, red and white and a bluish-white incarnation with a hint of the traces of the flagellation in blue corresponded to this. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Further examples

Crucifixion (Calvary), Southern Netherlands, c. 1430-1440, Oak, polychrome. The crucifixion of Christ is the most important event in the history of salvation because, according to the Christian faith, Christ made eternal life possible for mankind with his death on the cross. This is why this scene has been depicted so frequently. At first, art concentrated on the depiction of the crucified Christ himself, later a few assistant figures such as his mother Mary and his favorite disciple John the Evangelist were added. In the late Middle Ages, artists liked to tell stories and accordingly also depicted many events associated with the crucifixion of Christ. This is how the so-called figurative Calvaries came into being. This is a fragment of such a figurative crucifixion. Nevertheless, the great quality with which the central story of Christ is told here in a lifelike, detailed and moving way is clear. The actors, dressed in the fashion of the time, are grouped around the cross in a staggered, stage-like arrangement - for example, the blind Longinus on the left and the good centurion on the right, as well as servants and foot soldiers. Of the individually carved groups of figures, the women surrounding the mourning Mary (now privately owned in Switzerland) are missing, as is the scene of the soldiers throwing dice for Christ’s robe. The precise depiction of the events met the pronounced religious need for visualization of late medieval man and allowed him to experience the suffering of the Redeemer. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Crucifixion (Calvary), Southern Netherlands, c. 1430-1440, Oak, polychrome. The crucifixion of Christ is the most important event in the history of salvation because, according to the Christian faith, Christ made eternal life possible for mankind with his death on the cross. This is why this scene has been depicted so frequently. At first, art concentrated on the depiction of the crucified Christ himself, later a few assistant figures such as his mother Mary and his favorite disciple John the Evangelist were added. In the late Middle Ages, artists liked to tell stories and accordingly also depicted many events associated with the crucifixion of Christ. This is how the so-called figurative Calvaries came into being. This is a fragment of such a figurative crucifixion. Nevertheless, the great quality with which the central story of Christ is told here in a lifelike, detailed and moving way is clear. The actors, dressed in the fashion of the time, are grouped around the cross in a staggered, stage-like arrangement - for example, the blind Longinus on the left and the good centurion on the right, as well as servants and foot soldiers. Of the individually carved groups of figures, the women surrounding the mourning Mary (now privately owned in Switzerland) are missing, as is the scene of the soldiers throwing dice for Christ’s robe. The precise depiction of the events met the pronounced religious need for visualization of late medieval man and allowed him to experience the suffering of the Redeemer. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

The Virgin Mary surrounded by Female Virgin saints (Virgo inter virgines), Middle Rhine, c. 1430 Walnut, polychromy, gilded. Mary sits on a throne bench between two female saints; one step lower, two pairs of holy virgins each hold a sheet of music together. In its fine carving, the relief is designed for close-up viewing, presumably as the centerpiece of a small triptych for private devotion. Contemporary parallels to the depiction of Mary in the circle of holy virgins have been preserved in painting, which shows the holy women in a paradise garden that is also a closed garden (hortus conclusus), a symbol of their virginity. The Cologne relief can be imagined against a gold background, perhaps with the suggestion of rays of sunlight behind Mary, as a crescent moon is placed at her feet in the relief. It is only on closer inspection that one recognizes the extensive carved additions, which, including their coloring, are of equally excellent quality as the original itself. One would like to think that these were not so much additions to lost parts as replacements of damaged ones. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

The Virgin Mary surrounded by Female Virgin saints (Virgo inter virgines), Middle Rhine, c. 1430 Walnut, polychromy, gilded. Mary sits on a throne bench between two female saints; one step lower, two pairs of holy virgins each hold a sheet of music together. In its fine carving, the relief is designed for close-up viewing, presumably as the centerpiece of a small triptych for private devotion. Contemporary parallels to the depiction of Mary in the circle of holy virgins have been preserved in painting, which shows the holy women in a paradise garden that is also a closed garden (hortus conclusus), a symbol of their virginity. The Cologne relief can be imagined against a gold background, perhaps with the suggestion of rays of sunlight behind Mary, as a crescent moon is placed at her feet in the relief. It is only on closer inspection that one recognizes the extensive carved additions, which, including their coloring, are of equally excellent quality as the original itself. One would like to think that these were not so much additions to lost parts as replacements of damaged ones. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

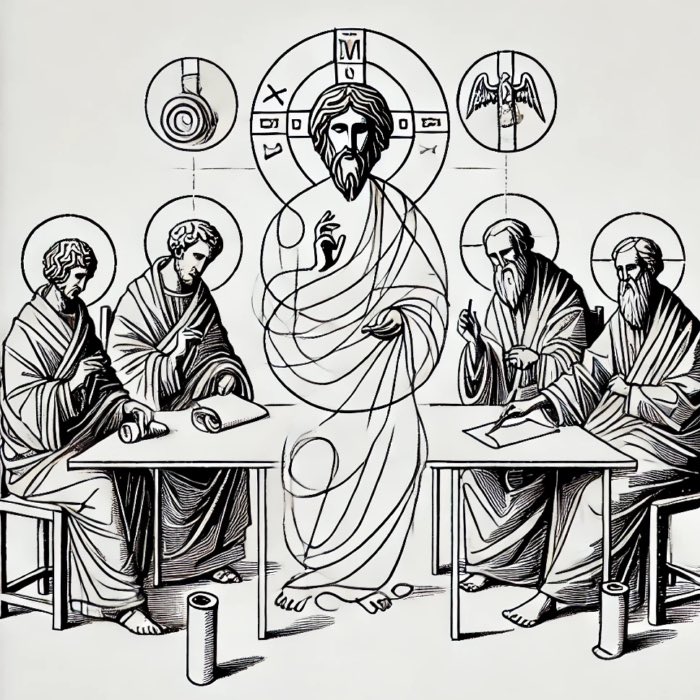

The Foot-Washing, Master of Viborg, Antwerp, c. 1515-1520, Oak, polychromy. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

The Foot-Washing, Master of Viborg, Antwerp, c. 1515-1520, Oak, polychromy. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Prophets from the altarpiece of the Church of the Crosiers in Cologne, Antwerp, Master of Viborg, c. 1515-1520, Oak, polychromy. In vividly animated poses, adorned with long banners as if made of parchment, whimsical beards and headdresses, curious garments, the figures of the four prophets are stately and at the same time entertaining figures with varied facial types. In this, they reflect the diversity of characters and fashionable extravagances that were popular in painting in the international trading city of Antwerp, situated on the North Sea. The figures, each virtuously carved from a shallow block of oak and preserved in their exquisite original paint, are of outstanding quality. They were originally part of a depiction of the Root of Jesse in one of the large altarpieces that were exported from Antwerp with great success at the beginning of the 16th century. There, they flanked the figure of the progenitor Jesse sleeping on a throne, above whom the twelve Old Testament ancestors of Jesus were usually arranged in a tree depiction, often with implied branches, along the frame of the central panel of the retable. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Prophets from the altarpiece of the Church of the Crosiers in Cologne, Antwerp, Master of Viborg, c. 1515-1520, Oak, polychromy. In vividly animated poses, adorned with long banners as if made of parchment, whimsical beards and headdresses, curious garments, the figures of the four prophets are stately and at the same time entertaining figures with varied facial types. In this, they reflect the diversity of characters and fashionable extravagances that were popular in painting in the international trading city of Antwerp, situated on the North Sea. The figures, each virtuously carved from a shallow block of oak and preserved in their exquisite original paint, are of outstanding quality. They were originally part of a depiction of the Root of Jesse in one of the large altarpieces that were exported from Antwerp with great success at the beginning of the 16th century. There, they flanked the figure of the progenitor Jesse sleeping on a throne, above whom the twelve Old Testament ancestors of Jesus were usually arranged in a tree depiction, often with implied branches, along the frame of the central panel of the retable. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Saintly Virgin (Mary?), Cologne, Workshop of Master Tilman (?), с. 1500, Oak, polychromy. The saint, characterized as a virgin by her long, loose hair, is clothed in a dress under a cloak pulled over her body, the tip of which is tucked under her left arm. In her right hand she holds the stem of a (broken) lily or palm tree, her left hand is lost. Turning slightly to her left, she opens her cloak and lowers her head slightly, which is why we could see Mary in the Annunciation scene; however, she could also be depicting another saint. The confidently captured posture and graceful movement add to the charm and quality of the figure, while the folded relief of the cloak appears comparatively schematic. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Saintly Virgin (Mary?), Cologne, Workshop of Master Tilman (?), с. 1500, Oak, polychromy. The saint, characterized as a virgin by her long, loose hair, is clothed in a dress under a cloak pulled over her body, the tip of which is tucked under her left arm. In her right hand she holds the stem of a (broken) lily or palm tree, her left hand is lost. Turning slightly to her left, she opens her cloak and lowers her head slightly, which is why we could see Mary in the Annunciation scene; however, she could also be depicting another saint. The confidently captured posture and graceful movement add to the charm and quality of the figure, while the folded relief of the cloak appears comparatively schematic. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Eligius Retabel, Workshop or Circle of Niklaus Weckmann, 1519, from the Chapel St. Eligius in Meßkirch, lime and softwood, polychrome. On either side are the coats of arms of the donors Gottfried Werner von Zimmern and his wife Apollonia von Henneberg. Perhaps the small figure kneeling on the left in front of the beautifully armed knight is the Lord of Zimmern himself, as Quirinus was the patron saint of knighthood. St. Leonhard, who stands on the right above Apollonia’s coat of arms, was invoked both in cases of cattle plagues and to help pregnant women. Finally, St. Eligius, raised in the middle, was the patron saint of all metal craftsmen and blacksmiths. In 1806, the chapel at the gates of Meßkirch, for which the altar was made, was demolished. Today the wings are lost. But the magnificent effect of the small stage for the three figures of saints with richly gilded robes can still be felt. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Eligius Retabel, Workshop or Circle of Niklaus Weckmann, 1519, from the Chapel St. Eligius in Meßkirch, lime and softwood, polychrome. On either side are the coats of arms of the donors Gottfried Werner von Zimmern and his wife Apollonia von Henneberg. Perhaps the small figure kneeling on the left in front of the beautifully armed knight is the Lord of Zimmern himself, as Quirinus was the patron saint of knighthood. St. Leonhard, who stands on the right above Apollonia’s coat of arms, was invoked both in cases of cattle plagues and to help pregnant women. Finally, St. Eligius, raised in the middle, was the patron saint of all metal craftsmen and blacksmiths. In 1806, the chapel at the gates of Meßkirch, for which the altar was made, was demolished. Today the wings are lost. But the magnificent effect of the small stage for the three figures of saints with richly gilded robes can still be felt. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

St. Anne with the Virgin and Child, Cologne, c. 1500 Wood, polychromy. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

St. Anne with the Virgin and Child, Cologne, c. 1500 Wood, polychromy. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Pietà, Cologne or Middle Rhine, c. 1380 Walnut, traces of old polychromy, pastiglia, edging cast. Mary, the Mother of God, gazes with sorrow at her dead son lying on her lap. In this small devotional painting, the mother’s sorrow is mixed with the clear references to the Passion suffered in the depiction of the dead Christ. In addition to Pietà (piety), these depictions are also known as Vespers images, as the Lamentation of Christ was commemorated on Good Friday at the time of Vespers. The motif of the mother mourning her dead son does not appear in the Gospels of the Bible and has a different origin. In the piety of mysticism, an attempt was also made to confront the Passion in particular by empathizing with the experience of Mary. Around 1300, the Pietà thus found its way into medieval art as a new type of image, detached from the sequence of the Descent from the Cross, Lamentation and Entombment. The small-format work of art was once displayed either in a church or a private house. By immersing themselves in the mourning scene, through their compassion, the viewer was able to comprehend the Passion of Christ. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Pietà, Cologne or Middle Rhine, c. 1380 Walnut, traces of old polychromy, pastiglia, edging cast. Mary, the Mother of God, gazes with sorrow at her dead son lying on her lap. In this small devotional painting, the mother’s sorrow is mixed with the clear references to the Passion suffered in the depiction of the dead Christ. In addition to Pietà (piety), these depictions are also known as Vespers images, as the Lamentation of Christ was commemorated on Good Friday at the time of Vespers. The motif of the mother mourning her dead son does not appear in the Gospels of the Bible and has a different origin. In the piety of mysticism, an attempt was also made to confront the Passion in particular by empathizing with the experience of Mary. Around 1300, the Pietà thus found its way into medieval art as a new type of image, detached from the sequence of the Descent from the Cross, Lamentation and Entombment. The small-format work of art was once displayed either in a church or a private house. By immersing themselves in the mourning scene, through their compassion, the viewer was able to comprehend the Passion of Christ. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Flight to Egypt, Netherlands, c. 1510-1520 (?), Wood (Walnut?) with traces of polychromy. Joseph strides forward with a serious expression and his luggage shouldered on a branch. Mary sits to the side on a donkey and holds the lively Christ Child, who is obviously enjoying the ride. It is possible that the small group of figures of the Holy Family on the Flight into Egypt was part of a large altarpiece with scenes from the life of Jesus, for example in the predella. However, on the Lower Rhine and in the Netherlands around 1500, such scenes are often accompanied by the suggestion of a landscape. The veneration of Joseph as the patron saint of carpenters and the Holy Family was evidently widespread on the Lower Rhine and in the Netherlands. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Flight to Egypt, Netherlands, c. 1510-1520 (?), Wood (Walnut?) with traces of polychromy. Joseph strides forward with a serious expression and his luggage shouldered on a branch. Mary sits to the side on a donkey and holds the lively Christ Child, who is obviously enjoying the ride. It is possible that the small group of figures of the Holy Family on the Flight into Egypt was part of a large altarpiece with scenes from the life of Jesus, for example in the predella. However, on the Lower Rhine and in the Netherlands around 1500, such scenes are often accompanied by the suggestion of a landscape. The veneration of Joseph as the patron saint of carpenters and the Holy Family was evidently widespread on the Lower Rhine and in the Netherlands. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

So-called Kendenich Madonna, Cologne, c. 1270-1280, Walnut, oak (back-board), polychrome. The figure was carved almost entirely from one piece of wood, only the parts that are now lost were carved and attached separately. The dowel holes in the right upper arm and on the left thigh are clearly visible. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

So-called Kendenich Madonna, Cologne, c. 1270-1280, Walnut, oak (back-board), polychrome. The figure was carved almost entirely from one piece of wood, only the parts that are now lost were carved and attached separately. The dowel holes in the right upper arm and on the left thigh are clearly visible. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Saint Peter, Cologne, c. 1315-1320 Walnut, polychrome. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Saint Peter, Cologne, c. 1315-1320 Walnut, polychrome. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

St. James the Greater (left) and St. James the Less (right) from the Altar of the Poor Clares in Cologne Cathedral, Cologne, c. 1360. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

St. James the Greater (left) and St. James the Less (right) from the Altar of the Poor Clares in Cologne Cathedral, Cologne, c. 1360. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

So-called Ollesheim Madonna, Cologne, c. 1260-1270, beech, polychrome. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

So-called Ollesheim Madonna, Cologne, c. 1260-1270, beech, polychrome. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Conclusion

Medieval wood sculptures represent a confluence of artistic mastery, religious devotion, and personal expression. They offer a rich insights into the medieval world and continue to fascinate and inspire. Today, these medieval sculptures transcend their religious origins, in my opinion, allowing to connect with them on various levels. They serve as a gateway to understanding the medieval mindset and spirituality, offering insights into the era’s social, cultural, and religious context. For the modern viewer, these sculptures offer a unique perspective on history and at the same time enable a very individual and very personal experience.

If you are interested in medieval art, I highly recommend visiting the Museum Schnütgen in Cologne, which houses an impressive collection of medieval wood sculptures. Another great place to view and study medieval wood sculptures is the Bode Museumꜛ in Berlin. I had the opportunity to visit this museum last year and I summarized my impression in this post. If you know further places for viewing medieval wood sculptures, please let us know in the comments below.

References and further reading

- Ulrike Bergmann, Schnütgen-Museum: Die Holzskulpturen des Mittelalters (1000-1400), 1989, Hrsg.: Anton Legner, Druckerei Locher GmbH, 5000 Köln 51

- Reinhard Karrenbrock, Schnütgen-Museum: Die Holzskulpturen des Mittelalters II. (1400-1540), 2001, Hrsg.: Hiltrud Westermann-Angerhausen

- Manuela Beer, Moritz Woelk, Museum Schnütgen - Handbuch zur Sammlung, 2018, Hirmer, ISBN: 9783777428932

- Museum Schnütgen, Das Mittelalter in 111 Meisterwerken aus dem Museum Schnütgen Köln, 2003, Greven, ISBN: 9783774303416

- Rainer Budde, Albert Hirmer, Irmgard Ernstmeier-Hirmer, Deutsche romanische Skulptur, 1050-1250, 1979, Hirmer, ISBN: 9783777430904

- Tobias Kunz, Bildwerke nördlich der Alpen 1050 bis 1380 - Kritischer Bestandskatalog der Berliner Skulpturensammlung, 2014, Michael Imhof Verlag, ISBN: 9783865689269

- Tobias Kunz, Bildwerke nördlich der Alpen und im Alpenraum 1380 bis 1440 - Kritischer Bestandskatalog der Berliner Skulpturensammlung, 2019, Michael Imhof Verlag, ISBN: 9783731907558

- Matthias Weniger, Tilmann Riemenschneider, 2016, Michael Imhof Verlag, ISBN: 9783731904755

- Guido De Werd, Moritz Woelk, Arnt, der Bilderschneider - Meister der beseelten Skulpturen, 2020, Hirmer, ISBN: 9783777434926

- Michael Grandmontagne, Tobias Kunz, Skulptur um 1300 - Zwischen Paris und Köln, 2016, Michael Imhof Verlag, ISBN: 9783731904243

- Jürgen Kaiser, Florian Monheim, Gotik im Rheinland, 2011, Greven, ISBN: 9783774304833

- Julien Chapuis, Svea Janzen, Stephan Kemperdick, Lothar Lambacher, Jan Friedrich Richter, Michael Roth, Late Gothic - The Birth Of Modernity, 2021, Hatje Cantz Verlag, ISBN: 9783775747547

comments