Faith and commerce: The medieval relic trade in Cologne

During my last visit to the Schnütgen Museum, I noticed a series of elaborate reliquary busts. These intricately crafted artifacts were shaped like the upper bodies of figures meant to represent saints, kings, and queens. Each bust had an opening to enclose and hold the corresponding relic. Their skillful artistry was immediately striking. Intrigued by this encounter, I began to do some research, uncovering a fascinating yet ironic chapter in the history of Cologne.

Reflections of relic busts in an exhibition case. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Reflections of relic busts in an exhibition case. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Introduction

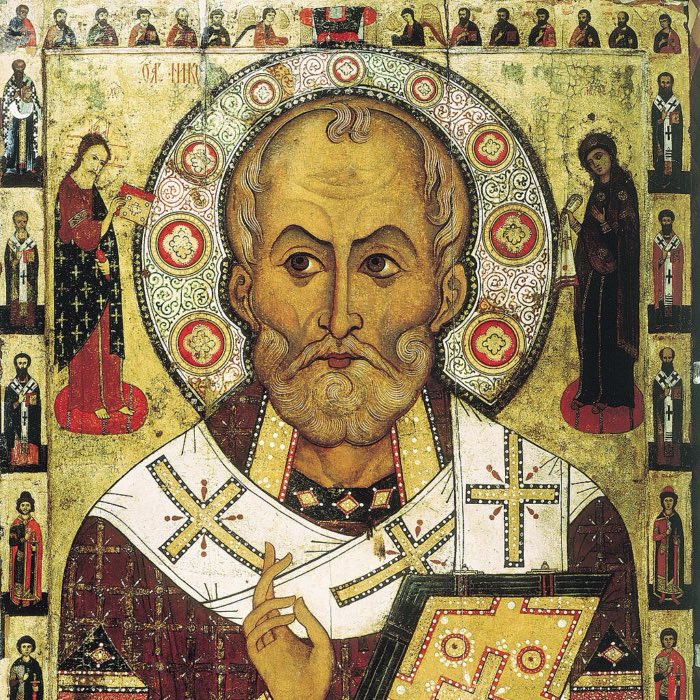

Christian relics, venerated in the medieval period, are physical objects associated with Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, the apostles, or other saints. These range from body parts (bones, hair, teeth) to items purportedly used by or associated with these holy figures, such as pieces of the True Cross. In medieval Europe, relics were not just spiritual symbols; they were pivotal in religious practices, believed to have miraculous powers, including healing the sick and providing protection.

The authenticity of relics has been a subject of debate and research. While some relics have been revered for centuries, modern scientific methods, including carbon dating and DNA analysis, have cast doubt on many. The Church, historically, has been cautious about officially authenticating relics. The authenticity often lies more in the faith and tradition surrounding the relic than in empirical evidence.

Reliquary, Lower Saxony, 2nd half of the 12th cent., Yellow brass. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Reliquary, Lower Saxony, 2nd half of the 12th cent., Yellow brass. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Reliquary pendant, Trier, c. 1270 (?), Silver, gilded. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Reliquary pendant, Trier, c. 1270 (?), Silver, gilded. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Reliquary cross, Rhine-Meuse Region,, c. 1220-30, Brass, gilded, rock crystal. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Reliquary cross, Rhine-Meuse Region,, c. 1220-30, Brass, gilded, rock crystal. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Top: Cylinder-reliquary of St. Brigitta, 15th century (?), rass, gilded, rock crystal. Bottom: Cylinder-reliquary of St. Bartholomew, Cologne, 14th century, Copper, gilded, rock crystal. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Top: Cylinder-reliquary of St. Brigitta, 15th century (?), rass, gilded, rock crystal. Bottom: Cylinder-reliquary of St. Bartholomew, Cologne, 14th century, Copper, gilded, rock crystal. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Reliquary with nail from the Cross, Cologne, c. 1500, Silver, partly gilded. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Reliquary with nail from the Cross, Cologne, c. 1500, Silver, partly gilded. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Cologne and the pilgrimage route

Cologne, a significant stop on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela, was a major medieval pilgrimage destination. This prominence was not only due to its spiritual significance but also because of its strategic location, which made it accessible to pilgrims from across Europe.

In Cologne, the intertwining of piety and profit was particularly evident. The city, clergy, and local merchants understood the economic benefits of the influx of pilgrims. The construction of the Cologne Cathedral can be seen as a monumental testament to this. Ostensibly built to house the Shrine of the Three Kings, a reputed reliquary of the remains of the Biblical Magi, the cathedral, even not completed, served both spiritual and economic purposes. It was a spiritual center for pilgrims and a symbol of the city’s wealth and prestige.

Pilgrims in Cologne could indeed purchase relics, which, in a sense, functioned as spiritual merchandise. This practice was not unique to Cologne but was widespread in medieval Europe. A famous example is the multiple relics of Saint John the Baptist; it is humorously noted that if all the relics attributed to him were gathered, one could assemble numerous skulls. This points to a certain commercial opportunism, where the demand for relics sometimes led to dubious practices.

The interior of the Cologne Cathedral.

The interior of the Cologne Cathedral.

The interior of the Cologne Cathedral.

The interior of the Cologne Cathedral.

Sketch of the medieval shrine of the Magi. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Sketch of the medieval shrine of the Magi. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

The medieval inner wooden construction of the shrine of the Magi, with remains of the reconstruction of 1807, Cologne, end of the 12th century, Wilhelm Pullack, 1807, Oak, glass, copper, gilded. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne. On the 23rd July 1164 the relics of the Magi were transferred from Milan to Cologne by Rainald von Dassel. Thus a new chapter in the history of Cologne Cathedral began. Possessing the relics of the Magi turned the cathedral into one of the most important destinations for pilgrimages within Christendom. Rulers from all over the world and especially the German kings worshipped the relics of royal ranking as model for their worldly kingdoms. They thus got the status of state relics. It took over twenty years until after 1190 Nikolaus von Verdun, one of the most famous goldsmiths of the Middle Ages, started working on the shrine of the Magi. Following his design the architecture of the shrine was divided into two zones and three parts. Until its completion about 1220 several workshops worked on the valuable ornamental fitting of the shrine. As to size and preciousness and due to the claims concerning its contents, the shrine of the Magi surpasses every reliquary, which has been built before in the Rhine-Maas region. In the cause of the centuries the shrine suffered numerous thefts and damages. The most important losses occurred during its evacuation caused by the occupation of the Rhineland by the French revolutionary troops from 1794 onwards. Due to the loss of numerous ornamental fittings, precious stones and filigree plates, the shrine had to be shortened by one bay when it was restored in 1807. According to the plan of the Cologne canon Ferdinand Franz Wallraf, the lost reliefs of the roof were replaced by two cycles of pictures: one showing scenes of the Old Testament, the other scenes of the history of the relics of the Magi. Wallraf also let the upper parts of the roofs be embellished by reliefs of angels set on blue glass. The last restoration of the shrine, dating from 1961 to 1973, gave the shrine to an extensive degree its original form back. The attempt to reconstruct the medieval state made it necessary to replace the medieval inner wooden construction by a new one, again made of oak. The medieval construction is now, after its restoration, on display in the treasury.

The medieval inner wooden construction of the shrine of the Magi, with remains of the reconstruction of 1807, Cologne, end of the 12th century, Wilhelm Pullack, 1807, Oak, glass, copper, gilded. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne. On the 23rd July 1164 the relics of the Magi were transferred from Milan to Cologne by Rainald von Dassel. Thus a new chapter in the history of Cologne Cathedral began. Possessing the relics of the Magi turned the cathedral into one of the most important destinations for pilgrimages within Christendom. Rulers from all over the world and especially the German kings worshipped the relics of royal ranking as model for their worldly kingdoms. They thus got the status of state relics. It took over twenty years until after 1190 Nikolaus von Verdun, one of the most famous goldsmiths of the Middle Ages, started working on the shrine of the Magi. Following his design the architecture of the shrine was divided into two zones and three parts. Until its completion about 1220 several workshops worked on the valuable ornamental fitting of the shrine. As to size and preciousness and due to the claims concerning its contents, the shrine of the Magi surpasses every reliquary, which has been built before in the Rhine-Maas region. In the cause of the centuries the shrine suffered numerous thefts and damages. The most important losses occurred during its evacuation caused by the occupation of the Rhineland by the French revolutionary troops from 1794 onwards. Due to the loss of numerous ornamental fittings, precious stones and filigree plates, the shrine had to be shortened by one bay when it was restored in 1807. According to the plan of the Cologne canon Ferdinand Franz Wallraf, the lost reliefs of the roof were replaced by two cycles of pictures: one showing scenes of the Old Testament, the other scenes of the history of the relics of the Magi. Wallraf also let the upper parts of the roofs be embellished by reliefs of angels set on blue glass. The last restoration of the shrine, dating from 1961 to 1973, gave the shrine to an extensive degree its original form back. The attempt to reconstruct the medieval state made it necessary to replace the medieval inner wooden construction by a new one, again made of oak. The medieval construction is now, after its restoration, on display in the treasury.

Shrine of St. Engelbert, Conrad Duisbergh (goldsmith’s work), Jeremias Geisselbrunn (design of the sculpture), Augustin Braun (design of the reliefs). Cologne, 1633, Silver, partly gilded. On the narrow sides of the shrine are depicted the Adoration of the Magi and Christ as Ruler of the world, between St, Peter and St, Maternus, the first bishop of Cologne. On the broad sides appear ten more holy bishops of Cologne, so that Archbishop Engelbert, who was murdered in 1225, is twelfth in this series of saints. Between the statues of the bishops are eight silver reliefs which illustrate the saint’s life. Eight more reliefs on the lid portray the legendary miracles at his tomb in Cologne Cathedral The shrine is crowned with the recumbent figure of St, Engelbert The adoration of St. Engelbert was revived in the early 17th century, where he counted both as a saint of the Counter Reformation and as the Patron Saint of the Catholic party in the Thirty Years’ War. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Shrine of St. Engelbert, Conrad Duisbergh (goldsmith’s work), Jeremias Geisselbrunn (design of the sculpture), Augustin Braun (design of the reliefs). Cologne, 1633, Silver, partly gilded. On the narrow sides of the shrine are depicted the Adoration of the Magi and Christ as Ruler of the world, between St, Peter and St, Maternus, the first bishop of Cologne. On the broad sides appear ten more holy bishops of Cologne, so that Archbishop Engelbert, who was murdered in 1225, is twelfth in this series of saints. Between the statues of the bishops are eight silver reliefs which illustrate the saint’s life. Eight more reliefs on the lid portray the legendary miracles at his tomb in Cologne Cathedral The shrine is crowned with the recumbent figure of St, Engelbert The adoration of St. Engelbert was revived in the early 17th century, where he counted both as a saint of the Counter Reformation and as the Patron Saint of the Catholic party in the Thirty Years’ War. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Reliquary monstrance of SS. Damian and Laurence, Alois Kreiten, Cologne, End of the 19th century, Copper, gilded. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Reliquary monstrance of SS. Damian and Laurence, Alois Kreiten, Cologne, End of the 19th century, Copper, gilded. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Left: Reliquary, Johann Heinrich Rohr, Cologne, c. 1760, Silver, silded. Right: Reliquary monstrance of SS. Amandus and Matthias Wendel Dederichs, Cologne, c. 1620, 19th century (tower, cross) Silver, enamel, rock crystal. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Left: Reliquary, Johann Heinrich Rohr, Cologne, c. 1760, Silver, silded. Right: Reliquary monstrance of SS. Amandus and Matthias Wendel Dederichs, Cologne, c. 1620, 19th century (tower, cross) Silver, enamel, rock crystal. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Bust-reliquary of St. Sebastian Franz Wüsten, Cologne, 1875, silver, partly gilded, enamel, precious stones. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Bust-reliquary of St. Sebastian Franz Wüsten, Cologne, 1875, silver, partly gilded, enamel, precious stones. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Left: Reliquary of the Cross with spectacle-glass, Workshop of Hans von Reutlingen, Aachen, beginning of the 16th century Silver, gilded, spectacle-glass. Right: Reliquary of the Cross, Cologne, 1510 and 1551 (base), Silver, copper, brass, gilded, precious stones. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Left: Reliquary of the Cross with spectacle-glass, Workshop of Hans von Reutlingen, Aachen, beginning of the 16th century Silver, gilded, spectacle-glass. Right: Reliquary of the Cross, Cologne, 1510 and 1551 (base), Silver, copper, brass, gilded, precious stones. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Reliquary of the Cross from St. Mary ad Gradus, Constantinople, middle and end of the 12th century (figures and ornaments on the wings), Cologne, c. 1240 (remaining goldsmith’s work), Silver, copper, gilded, precious stones, pearls. The reliquary was reset in late Romanesque times with pieces of a Byzantine staurotheque (relic-casket of the Cross). On the inner sides of the wings the Emperor Constantine and his mother Helena are portrayed, on the outer sides Mary and John. The relic of the Cross is surrounded by four angels. On the reverse, the enthroned Christ appears with the symbols of the Evangelists. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Reliquary of the Cross from St. Mary ad Gradus, Constantinople, middle and end of the 12th century (figures and ornaments on the wings), Cologne, c. 1240 (remaining goldsmith’s work), Silver, copper, gilded, precious stones, pearls. The reliquary was reset in late Romanesque times with pieces of a Byzantine staurotheque (relic-casket of the Cross). On the inner sides of the wings the Emperor Constantine and his mother Helena are portrayed, on the outer sides Mary and John. The relic of the Cross is surrounded by four angels. On the reverse, the enthroned Christ appears with the symbols of the Evangelists. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Relic Case, Cologne, about 1300 (tracery fronts), 19th century (cases), wood, with remains of coloration. These relic cases hung until the 19th century in the sacristy consecrated in 1277, which is today the Chapel of the Sacrament. Then, from the 19th century until 1999, they were exhibited in the tower halls of the cathedral. They contain numerous not identified relics, covered with fabric. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Relic Case, Cologne, about 1300 (tracery fronts), 19th century (cases), wood, with remains of coloration. These relic cases hung until the 19th century in the sacristy consecrated in 1277, which is today the Chapel of the Sacrament. Then, from the 19th century until 1999, they were exhibited in the tower halls of the cathedral. They contain numerous not identified relics, covered with fabric. Cathedral Treasury of Cologne Cathedral, Cologne.

Papal intervention and Cologne’s ingenious response

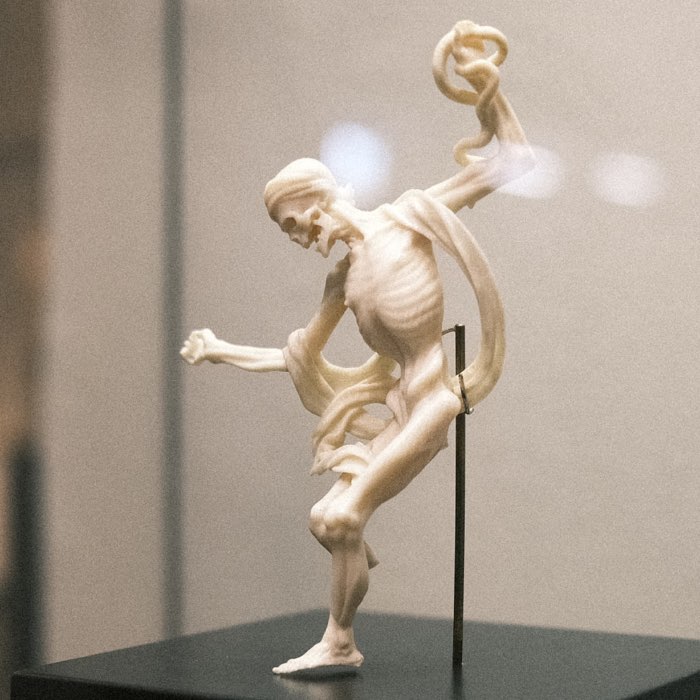

As I learned during a guided tour of the Museum Schnütgen, the Church, particularly the papacy, was not always comfortable with the commercialization of relics. In response to the growing commercialization of relics, the Church began to regulate the relic trade, condemning the sale of fake relics and the unscrupulous profit-making from genuine ones. However, Cologne adapted cleverly to these regulations. The city’s artisans began crafting exquisite reliquaries, busts, crosses, and other items to house relics. These were not just containers but works of art, justifying their high prices. Thus, Cologne continued to thrive economically from the relic trade under the guise of piety and artistry.

Reliquary busts, mostly from Cologne, 14th-15th century, wood, partly polychrome. These busts were used to house relics of saints. The reliquary was placed inside the hollowed-out head or body of the bust. This collection was actually the inspiration for this post. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Reliquary busts, mostly from Cologne, 14th-15th century, wood, partly polychrome. These busts were used to house relics of saints. The reliquary was placed inside the hollowed-out head or body of the bust. This collection was actually the inspiration for this post. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Reliquary bust, Cologne, c. 1340, wood, partly polychrome. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Reliquary bust, Cologne, c. 1340, wood, partly polychrome. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Relquary bust, Cologne, 2nd quarter of the 14th cent., wood, partly polychrome. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Relquary bust, Cologne, 2nd quarter of the 14th cent., wood, partly polychrome. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

The Golden Chamber in St. Ursula, Cologne. The room is used to store the countless so-called Ursula relics and is the largest ossuary north of the Alps. Notable: The legend of St. Ursula has made it into the coat of arms of the city of Cologne.

The Golden Chamber in St. Ursula, Cologne. The room is used to store the countless so-called Ursula relics and is the largest ossuary north of the Alps. Notable: The legend of St. Ursula has made it into the coat of arms of the city of Cologne.

Conclusion

The case of Cologne in the medieval period presents a fascinating blend of devout piety and shrewd economic sense. While the primary motivation for many pilgrims was spiritual, the city and its clergy were not averse to capitalizing on this influx. This dual nature of deep faith and practical commerce reflects the complex interplay of religion, economy and power in medieval society. The relic trade in Cologne, thus, serves as a microcosm of this intricate relationship, where spiritual devotion and rational profit-seeking coexisted, sometimes uncomfortably, under the broad umbrella of medieval Christianity.

References and further reading

- Michael E. Habicht, Joachim H. Schleifring, Reliquien: Fachbuch und Reiseführer zu katholischen Reliquien weltweit, 2023, ISBN: 978-3757579357

- Arnold Angenendt, Heilige und Reliquien, 2007, ISBN: 978-3937872728

- Karlheinz Deschner, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums 3: Die Alte Kirche: Fälschung, Verdummung, Ausbeutung, Vernichtung, 1996, ISBN: 978-3499602443

- Karl Ubl, Köln im Frühmittelalter (400-1100): Die Entstehung einer heiligen Stadt: Geschichte der Stadt Köln, Band 2, 2022, ISBN: 978-3774304406

- Hugo Stehkämper, Carl Dietmar, Köln im Hochmittelalter. 1074/75-1288: Geschichte der Stadt Köln Band 3, 2016, ISBN:

- Wolfgang Herborn, Carl Dietmar, Köln im Spätmittelalter 1288-1512/13: Geschichte der Stadt Köln, Band 4, 2019,

comments