Beyond the sacred: Exploring medieval art at the Schnütgen Museum

The Schnütgen Museum in Cologneꜛ offers a unique and tangible experience of the European Middle Ages, presenting medieval art in a new light. Unlike the traditional setting in churches where these artworks are often embedded in religious practices and contexts, the museum enables a distinct viewing. Here, Christian sacred art is appreciated as individual pieces of artwork, accessible and detached from their usual religious environment. This approach is especially novel, considering that in their original settings, these pieces were often intertwined with religious practices and sometimes inaccessible to the general public. The Schnütgen Museum changes this, offering a rare opportunity to intimately explore medieval art outside of its conventional religious context.

Torso of a Crucifix from a Deposition from the Cross, Cologne (?), c. 1230-1240, Oak, polychromy.

Torso of a Crucifix from a Deposition from the Cross, Cologne (?), c. 1230-1240, Oak, polychromy.

Cologne in the Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages, Cologne was a significant center for trade, economy, and politics. Its strategic location on the Rhine River made it a hub for commerce and communication, linking northern and southern Europe. Cologne was also part of the Hanseatic League (“Hanse”), a powerful trading network that dominated the Baltic and North Sea regions. The city’s economic power was further bolstered by its influential guilds and its role as a political power center within the Holy Roman Empire.

A bird’s eye view of medieval Cologne. Woodcut by Anton Woensam from Worms, 1531, detail. The original is 352 cm wide. Exhibited in the Schnütgen Museum.

A bird’s eye view of medieval Cologne. Woodcut by Anton Woensam from Worms, 1531, detail. The original is 352 cm wide. Exhibited in the Schnütgen Museum.

Cologne also held a pivotal role in the spread and influence of Christianity, both regionally and beyond. Its numerous churches, monasteries, and religious institutions were centers for theological thought and education. The city was also a key player in the trade of relics, attracting pilgrims and tourists from far and wide. Furthermore, Cologne is laying on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela, one of the most important pilgrimage sites in Europe. The pilgrimage not only had religious significance but also contributed significantly to the city’s economy and social landscape.

The museum

The Schnütgen Museum in Cologne was founded due to the dedicated efforts of Alexander Schnütgen, a passionate collector of Christian art. His vision was to create a space that preserves and highlights the rich heritage of medieval art, with a particular focus on Christian sacred art. The museum’s inception was not rooted in religious motivations but rather in the cultural and artistic appreciation of these artifacts. This distinction set the tone for the museum’s approach, aiming to make these artworks accessible to a broader public audience, outside of a strictly religious context.

St. Cäcilien Church, the home of the Schnütgen Museum. The former church is fully integrated into the museum, creating a unique setting for the artworks on display.

St. Cäcilien Church, the home of the Schnütgen Museum. The former church is fully integrated into the museum, creating a unique setting for the artworks on display.

The museum is housed in a remarkable location – the St. Cäcilien, a Romanesque church, adding a layer of historical depth to the visitor’s experience. The church, with its own rich history dating back to the 12th century, was deconsecrated in 1802 and repurposed to become part of the museum in 1956. This transition from a religious to a cultural institution is a story in itself, reflective of the broader changes in society’s relationship with religious art and spaces.

The ancient walls of the former church create an ambiance that is both appropriate and impressive. The tall glass windows, vaulted ceilings, and other architectural elements of the church remain intact, offering a unique backdrop that complements the medieval artworks on display. This combination of historic architecture and art provides a holistic experience that immerses visitors in the medieval world. Furthermore, this architectural set up offers a unique opportunity to view the artworks in a setting that is similar to their original context, allowing for a more authentic experience.

The museum is located directly next to the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museumꜛ, a museum dedicated to ethnology and anthropology. The juxtaposition of these two museums is a unique feature of the Schnütgen Museum, highlighting the connections between medieval art and other cultures. This approach is also reflected in the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum’s collection, which includes artifacts from the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. These pieces are not only aesthetically beautiful but also provide insights into the cultural and religious practices of the time. Both museums share a common goal of preserving and presenting cultural heritage, albeit from different time periods and perspectives.

The exhibition

The layout of the museum is thoughtfully designed to guide visitors through a chronological and thematic journey of medieval art. From intricate sculptures and reliquaries to breathtaking stained glass and rare manuscripts, each exhibit is meticulously curated to provide insights into the craftsmanship, symbolism, and historical context of the period. The focus on Christian sacred art is evident throughout the museum, with a particular emphasis on the Cologne and Rhineland region. In addition to its permanent collection, the Schnütgen Museum also frequently hosts temporary exhibitions.

In the following, I’d like to share some of my favorite pieces from the museum’s permanent collection to provide a glimpse into the museum’s rich collection:

Adoration of the Magi from the so-called ‘Dreikönigenpförtchen’ at St. Maria im Kapitol in Cologne, Cologne, c. 1320-1330, Limestone, slight remains of polychromy. The group of figures comes from the inside of the portal at the “Lichhof” of St. Maria im Kapitol, the cemetery for pilgrims and travelers who died in Cologne. Cologne’s patron saints were also considered to be the patron saints of the city, for whose relics, brought to Cologne in 1164, the Gothic cathedral was built from 1248.

Adoration of the Magi from the so-called ‘Dreikönigenpförtchen’ at St. Maria im Kapitol in Cologne, Cologne, c. 1320-1330, Limestone, slight remains of polychromy. The group of figures comes from the inside of the portal at the “Lichhof” of St. Maria im Kapitol, the cemetery for pilgrims and travelers who died in Cologne. Cologne’s patron saints were also considered to be the patron saints of the city, for whose relics, brought to Cologne in 1164, the Gothic cathedral was built from 1248.

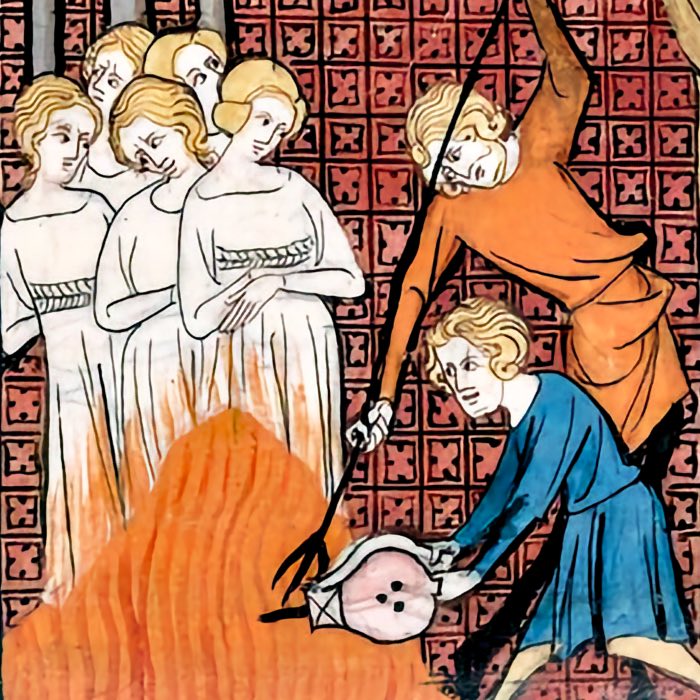

Tympanum from St. Cecilia in Cologne, Cologne, 3rd quarter of the 12th cent., Lorraine limestone, Norroy. When worshippers entered St. Cecilia’s Church through the north portal, they were greeted by their patron saint in the tympanum above and her virtue and martyrdom were presented to them as an example worthy of imitation. As a Christian, the Roman patrician’s daughter had vowed virginity. On her wedding day, she told her fiancé Valerianus that her innocence was guarded by an angel. Because he wanted to see the angel, he also converted to Christianity and convinced his older brother Tiburtius to do the same. On the tympanum, Cecilia is depicted between her fiancé and his brother. As they suffered martyrdom with Cecilia, they once held lost metal palms in their left hands as a sign of victory. The tympanum, which was probably originally painted, is composed of nine Roman stones, of which the Tiburtius plaque on the back still bears a Roman inscription.

Tympanum from St. Cecilia in Cologne, Cologne, 3rd quarter of the 12th cent., Lorraine limestone, Norroy. When worshippers entered St. Cecilia’s Church through the north portal, they were greeted by their patron saint in the tympanum above and her virtue and martyrdom were presented to them as an example worthy of imitation. As a Christian, the Roman patrician’s daughter had vowed virginity. On her wedding day, she told her fiancé Valerianus that her innocence was guarded by an angel. Because he wanted to see the angel, he also converted to Christianity and convinced his older brother Tiburtius to do the same. On the tympanum, Cecilia is depicted between her fiancé and his brother. As they suffered martyrdom with Cecilia, they once held lost metal palms in their left hands as a sign of victory. The tympanum, which was probably originally painted, is composed of nine Roman stones, of which the Tiburtius plaque on the back still bears a Roman inscription.

Capitals from the portal of the so-called Paradies of the Abbey of Maria Laach, Samson-Master, c. 1220, Lorraine limestone, Norroy type, traces of polychromy, original toolmarks from flat chisel, compass arcs, and scored marks On loan from Maria Laach, Benedictine Abbey.

Capitals from the portal of the so-called Paradies of the Abbey of Maria Laach, Samson-Master, c. 1220, Lorraine limestone, Norroy type, traces of polychromy, original toolmarks from flat chisel, compass arcs, and scored marks On loan from Maria Laach, Benedictine Abbey.

Fragment of a robed figure, Cologne, late 10th cent. / 1st third 11th cent., Shelly limestone, Cologne, St. Pantaleon. After the burial of Archbishop Bruno in the Church of St. Pantaleon in 965, the Benedictine abbey he had recently founded underwent extensive reconstruction, during which the remains of St. Maurinus were discovered. Some twenty years later, a gift from Empress Theophanu also brought the relics of St. Albinus to the Church of St. Pantaleon. The Albinus altar, near which the empress was buried in 991, occupied a central position in the western annex of the church. Perhaps as early as the end of the 10th century, but no later than the 1020s, the westwork was renovated. The facade of the building was decorated with an elaborate, monumental sculptural programme, of which three special fragments are on display here. The figure of Christ occupied a central position in the three-storey structure. The larger-than-life head of his sculpture has survived. The fragment of a beardless head probably belongs to an angel. The fragment of the life-size robed figure of a male saint could have been one of the church’s patrons or even Albinus.

Fragment of a robed figure, Cologne, late 10th cent. / 1st third 11th cent., Shelly limestone, Cologne, St. Pantaleon. After the burial of Archbishop Bruno in the Church of St. Pantaleon in 965, the Benedictine abbey he had recently founded underwent extensive reconstruction, during which the remains of St. Maurinus were discovered. Some twenty years later, a gift from Empress Theophanu also brought the relics of St. Albinus to the Church of St. Pantaleon. The Albinus altar, near which the empress was buried in 991, occupied a central position in the western annex of the church. Perhaps as early as the end of the 10th century, but no later than the 1020s, the westwork was renovated. The facade of the building was decorated with an elaborate, monumental sculptural programme, of which three special fragments are on display here. The figure of Christ occupied a central position in the three-storey structure. The larger-than-life head of his sculpture has survived. The fragment of a beardless head probably belongs to an angel. The fragment of the life-size robed figure of a male saint could have been one of the church’s patrons or even Albinus.

Arch segment with dragon and Human Head, Cologne, c. 1200-1230, Limestone.

Arch segment with dragon and Human Head, Cologne, c. 1200-1230, Limestone.

Left: St. Clara, Cologne, c. 1520-1530, Stained glass. Right: The Baptism of Christ, Lower Rhine, c. 1510, Stained glass. The museum hosts a large collection of stained glass windows. The windows are displayed in a way that allows visitors to appreciate the intricate details and vibrant colors of these pieces.

Left: St. Clara, Cologne, c. 1520-1530, Stained glass. Right: The Baptism of Christ, Lower Rhine, c. 1510, Stained glass. The museum hosts a large collection of stained glass windows. The windows are displayed in a way that allows visitors to appreciate the intricate details and vibrant colors of these pieces.

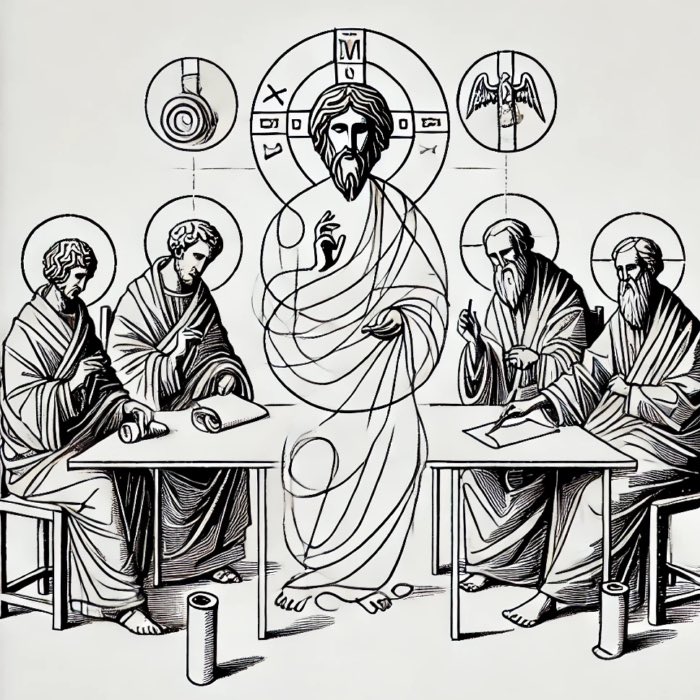

The Last Supper (upper images and Christ on the Mount of Olives (lower image) from the former sacrament house of Cologne Cathedral, after 1508, Baumberg Sandstone. The two stone reliefs come from the sacrament house in Cologne Cathedral, which was demolished in 1768 in the course of the baroqueization of the high choir. Embedded in a Gothic case, probably 18 meters high, the reliefs were probably placed above the cupboard for storing the hosts. – The narrative image: Christ and his disciples have gathered around an almost square table for the Last Supper, on which the dishes of the Passover meal can be seen with the roasted lamb, bread, knife and a tall medieval glass cup studded with domes. The apostles react emotionally to the announcement that one of them will betray Christ. Excited, they turn and turn towards each other. Only Judas is depicted as a standing figure, hiding the purse at the back in a left-handed turn, while he turns towards Christ at the head end, with Peter highlighted at his side. A counterpoint to the traitor is the sleeping John, who does not lean against Christ’s chest, as in numerous other depictions of the Last Supper, but rather supports himself on his arm. The scene on the Mount of Olives is similarly expressive, with Jesus kneeling in prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane on the night before his crucifixion. He is surrounded in a semicircle by the disciples Peter, James and John, who are sleeping in different positions. As in the Last Supper, the drapery is not limited to a natural drape resulting from the postures. Rather, the tension of the scene is heightened with the help of the sometimes burr-like, nervous fold breaks, deep undercuts and dynamic sweeps. The fenced-in, rocky garden is enlivened by individual plants and creepers. In the background is the city wall of Jerusalem.

The Last Supper (upper images and Christ on the Mount of Olives (lower image) from the former sacrament house of Cologne Cathedral, after 1508, Baumberg Sandstone. The two stone reliefs come from the sacrament house in Cologne Cathedral, which was demolished in 1768 in the course of the baroqueization of the high choir. Embedded in a Gothic case, probably 18 meters high, the reliefs were probably placed above the cupboard for storing the hosts. – The narrative image: Christ and his disciples have gathered around an almost square table for the Last Supper, on which the dishes of the Passover meal can be seen with the roasted lamb, bread, knife and a tall medieval glass cup studded with domes. The apostles react emotionally to the announcement that one of them will betray Christ. Excited, they turn and turn towards each other. Only Judas is depicted as a standing figure, hiding the purse at the back in a left-handed turn, while he turns towards Christ at the head end, with Peter highlighted at his side. A counterpoint to the traitor is the sleeping John, who does not lean against Christ’s chest, as in numerous other depictions of the Last Supper, but rather supports himself on his arm. The scene on the Mount of Olives is similarly expressive, with Jesus kneeling in prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane on the night before his crucifixion. He is surrounded in a semicircle by the disciples Peter, James and John, who are sleeping in different positions. As in the Last Supper, the drapery is not limited to a natural drape resulting from the postures. Rather, the tension of the scene is heightened with the help of the sometimes burr-like, nervous fold breaks, deep undercuts and dynamic sweeps. The fenced-in, rocky garden is enlivened by individual plants and creepers. In the background is the city wall of Jerusalem.

Fragment of a Tabernacle with Saints Agnes and Dorothea, Cologne, 1475-1500, Baumberg Sandstone.

Fragment of a Tabernacle with Saints Agnes and Dorothea, Cologne, 1475-1500, Baumberg Sandstone.

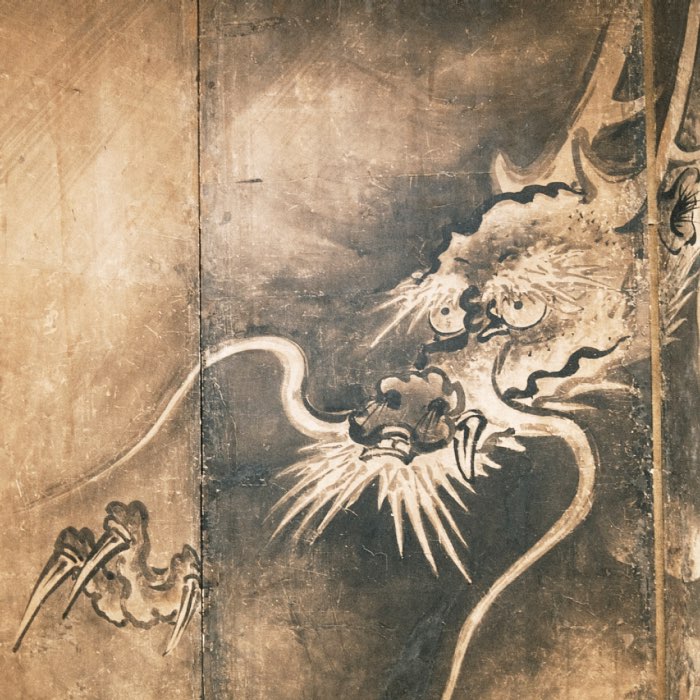

St. George, Middle Rhine, c. 1420, Oak, stripped of polychromy, base panel and lance replaced. According to legend, St. George freed a town from a dragon, to which people were regularly sacrificed and, in the end, almost a princess. As a result, the citizens converted to the Christian faith. As a Christian soldier, George later became a martyr. Like St. Michael the Archangel, who also appeared as a knight, and St. Christopher the Giant, he is one of the most popular saints of the late Middle Ages. Like these two, he was not only used in sculpture as part of altar retables, but also as a single sculpture in the church interior. George also embodies the ideal image of the Christian knight. The legendary battle of St. George against the dragon, which he first wrestles down with his lance and makes submissive to the king’s daughter before later killing him with his sword, is soothed in this sculpture from the dramatic to the playful. The knight with the lance on his little horse appears almost childishly dreamy. The heads of the dragon and horse are pointing in different directions, the dragon’s tail is curled around the horse’s left hind leg.

St. George, Middle Rhine, c. 1420, Oak, stripped of polychromy, base panel and lance replaced. According to legend, St. George freed a town from a dragon, to which people were regularly sacrificed and, in the end, almost a princess. As a result, the citizens converted to the Christian faith. As a Christian soldier, George later became a martyr. Like St. Michael the Archangel, who also appeared as a knight, and St. Christopher the Giant, he is one of the most popular saints of the late Middle Ages. Like these two, he was not only used in sculpture as part of altar retables, but also as a single sculpture in the church interior. George also embodies the ideal image of the Christian knight. The legendary battle of St. George against the dragon, which he first wrestles down with his lance and makes submissive to the king’s daughter before later killing him with his sword, is soothed in this sculpture from the dramatic to the playful. The knight with the lance on his little horse appears almost childishly dreamy. The heads of the dragon and horse are pointing in different directions, the dragon’s tail is curled around the horse’s left hind leg.

Angel with the Crown of Thorns, Westphalia, c. 1440, Baumberg sandstone. Particularly striking about this angel’s appearance is the copious mass of corkscrew curls that frame his idealized youthful face. In his left hand, the angel holds the Crown of Thorns. It is likely that he carried another symbol of the Passion in his missing right hand. The small figure may have originally belonged to a sacrament house or was part of a sculptural ensemble representing the suffering Christ.

Angel with the Crown of Thorns, Westphalia, c. 1440, Baumberg sandstone. Particularly striking about this angel’s appearance is the copious mass of corkscrew curls that frame his idealized youthful face. In his left hand, the angel holds the Crown of Thorns. It is likely that he carried another symbol of the Passion in his missing right hand. The small figure may have originally belonged to a sacrament house or was part of a sculptural ensemble representing the suffering Christ.

The Raising of St. Lazarus, Cologne, c. 1520, Baumberg sandstone, traces of polychromy. Initially, the disciples did not want to follow Jesus to Judah to the house of Lazarus, but now they stand behind him in a dense group that is staggered upwards. This powerful group of figures, in front of which Jesus stands out as the only figure not overlapped, forms one pole of the psychologically charged relief composition. On the other side stands a Jew wearing a pointed turban, holding his nose and turning away from Lazarus, who is sitting upright in the sarcophagus and gazing expectantly at Jesus with his hands clasped together in prayer. In the figure mediating between these two sides, who lays a hand on Lazarus’ head, we may recognize Peter, who removes the bandage from Lazarus’ hands, alluding to the power given to him by Jesus to bind and loose. It is striking that Mary, Lazarus’ sister, who plays an important role in the biblical narrative and appears in the pictorial tradition on the shelf, is not depicted here. While the edge of the relief behind the apostles is worked in such a way that a frame could well have been attached to it, the block on the side of the turban-bearer with his robe closes in a similar way to the inner joint between Peter and the group of Jesus with the apostles. This suggests that a narrower relief strip with the figures of Martha and Mary may originally have been attached to the left side.

The Raising of St. Lazarus, Cologne, c. 1520, Baumberg sandstone, traces of polychromy. Initially, the disciples did not want to follow Jesus to Judah to the house of Lazarus, but now they stand behind him in a dense group that is staggered upwards. This powerful group of figures, in front of which Jesus stands out as the only figure not overlapped, forms one pole of the psychologically charged relief composition. On the other side stands a Jew wearing a pointed turban, holding his nose and turning away from Lazarus, who is sitting upright in the sarcophagus and gazing expectantly at Jesus with his hands clasped together in prayer. In the figure mediating between these two sides, who lays a hand on Lazarus’ head, we may recognize Peter, who removes the bandage from Lazarus’ hands, alluding to the power given to him by Jesus to bind and loose. It is striking that Mary, Lazarus’ sister, who plays an important role in the biblical narrative and appears in the pictorial tradition on the shelf, is not depicted here. While the edge of the relief behind the apostles is worked in such a way that a frame could well have been attached to it, the block on the side of the turban-bearer with his robe closes in a similar way to the inner joint between Peter and the group of Jesus with the apostles. This suggests that a narrower relief strip with the figures of Martha and Mary may originally have been attached to the left side.

Christ in the dungeon, Circle of Johann Mauritz Gröniger, Münster, c. 1690, Baumberg sandstone, wooden thorns, traces of polychromy. The motif of the solitary Christ in the Dungeon emerged during the Baroque period. It can be considered another station of the Passion of Christ as described in the gospels, fitting between the stations of his arrest, flagellation, the placement of the crown of thorns and his crucifixion. The image was used by the faithful for devout meditations on the stations of the Cross Beyond its religious significance. The sculpture, which is attributed to Johann Mauritz Gröninger, can also be understood as the embodiment of human suffering and hope.

Christ in the dungeon, Circle of Johann Mauritz Gröniger, Münster, c. 1690, Baumberg sandstone, wooden thorns, traces of polychromy. The motif of the solitary Christ in the Dungeon emerged during the Baroque period. It can be considered another station of the Passion of Christ as described in the gospels, fitting between the stations of his arrest, flagellation, the placement of the crown of thorns and his crucifixion. The image was used by the faithful for devout meditations on the stations of the Cross Beyond its religious significance. The sculpture, which is attributed to Johann Mauritz Gröninger, can also be understood as the embodiment of human suffering and hope.

Pearl Ciborium, Lower Saxony, 2nd half of the 13th cent. Wooden core, embroidery with glass, freshwater and metal pearls and metal appliqué on parchment. This precious and extremely rare vessel of high artistic quality was created to hold the consecrated host, the Blessed Sacrament. The use of different materials in this ciborium is very special: parchment is stretched over a chalice-shaped wooden core, which is decorated all over with embroidered river and glass beads as well as metal appliqués. Various scenes from the history of salvation can be seen on a blue background: The Annunciation, the Crucifixion with Mary and John and the Coronation of Mary by Christ set in medallions. The symbols of the four evangelists adorn the lower part of the vessel and white lilies adorn the foot. Scenes from the Passion are embroidered on the conical lid: Flagellation and Carrying of the Cross. A gilded cross forms the crowning finial.

Pearl Ciborium, Lower Saxony, 2nd half of the 13th cent. Wooden core, embroidery with glass, freshwater and metal pearls and metal appliqué on parchment. This precious and extremely rare vessel of high artistic quality was created to hold the consecrated host, the Blessed Sacrament. The use of different materials in this ciborium is very special: parchment is stretched over a chalice-shaped wooden core, which is decorated all over with embroidered river and glass beads as well as metal appliqués. Various scenes from the history of salvation can be seen on a blue background: The Annunciation, the Crucifixion with Mary and John and the Coronation of Mary by Christ set in medallions. The symbols of the four evangelists adorn the lower part of the vessel and white lilies adorn the foot. Scenes from the Passion are embroidered on the conical lid: Flagellation and Carrying of the Cross. A gilded cross forms the crowning finial.

Top: Monstrance, Cologne, 2nd quarter of the 15th cent., Gilt copper with glass cylinder. Bottom: Tabernacle Door, Cologne, 2nd half of the 15th cent., Painting on wood. It shows two kneeling angels hold a detailed depiction of a late Gothic monstrance. At the center of the composition is the Blessed Sacrament, which is presented in the transparent cylinder of the monstrance. The figure of the crucified can be seen in silhouette on the surface of the host. The keyhole carved next to the left angel and two eyelets from a hinge on the right-hand edge of the picture bear witness to the original function of the round-arched panel painting: the painting served as the door to a sacramental niche (tabernacle) in which the consecrated hosts were kept.

Top: Monstrance, Cologne, 2nd quarter of the 15th cent., Gilt copper with glass cylinder. Bottom: Tabernacle Door, Cologne, 2nd half of the 15th cent., Painting on wood. It shows two kneeling angels hold a detailed depiction of a late Gothic monstrance. At the center of the composition is the Blessed Sacrament, which is presented in the transparent cylinder of the monstrance. The figure of the crucified can be seen in silhouette on the surface of the host. The keyhole carved next to the left angel and two eyelets from a hinge on the right-hand edge of the picture bear witness to the original function of the round-arched panel painting: the painting served as the door to a sacramental niche (tabernacle) in which the consecrated hosts were kept.

Left: Memento mori in the form of a small coffin, Southern Germany (7), 18th cent., wax figure on silk in a wooden coffin. Right: Memento mori in the form of a corpse, Germany, c. 1800, Ivory. Memento mori, “Remember death!”. Until modern times, this admonition served as an appeal to lead a godly life in the face of death, which was perceived as omnipresent. We should also not forget that Christianity in its origins was a religion of death and that the first Christians believed in the end of the world and the imminent return of Christ. As people usually died at home surrounded by family, friends and neighbors, death was part of everyday life in the Middle Ages. Death books, so-called artes moriendi (the art of dying) prepared the individual for the final hour. A process of repression of the subject of death only began with the Enlightenment in the 18th century. Memento mori - this is also the title of a genre of mostly small-figure wood and ivory works. Death grins at the viewer in the form of a corpse, cadaver, skeleton or skull. If he pleases as an actor, he embodies the grim reaper, gravedigger, minstrel or dancer.

Left: Memento mori in the form of a small coffin, Southern Germany (7), 18th cent., wax figure on silk in a wooden coffin. Right: Memento mori in the form of a corpse, Germany, c. 1800, Ivory. Memento mori, “Remember death!”. Until modern times, this admonition served as an appeal to lead a godly life in the face of death, which was perceived as omnipresent. We should also not forget that Christianity in its origins was a religion of death and that the first Christians believed in the end of the world and the imminent return of Christ. As people usually died at home surrounded by family, friends and neighbors, death was part of everyday life in the Middle Ages. Death books, so-called artes moriendi (the art of dying) prepared the individual for the final hour. A process of repression of the subject of death only began with the Enlightenment in the 18th century. Memento mori - this is also the title of a genre of mostly small-figure wood and ivory works. Death grins at the viewer in the form of a corpse, cadaver, skeleton or skull. If he pleases as an actor, he embodies the grim reaper, gravedigger, minstrel or dancer.

Dancing Death, Germany, c. 1700, ivory. The dancing movement in particular has a long tradition: it is rooted in the popular belief in the Middle Ages that the dead rise from their graves at midnight and perform a dance in the cemetery. From the end of the 14th century, the dance of death was also the motif for the “Black Death”, the plague. The most unusual and shocking aspect of the Dance of Death motif for contemporaries was the combination of the theme of death with dance - one of the most vital expressions of the joy and affirmation of life. This macabre combination of opposites will not have failed to have a moral effect.

Dancing Death, Germany, c. 1700, ivory. The dancing movement in particular has a long tradition: it is rooted in the popular belief in the Middle Ages that the dead rise from their graves at midnight and perform a dance in the cemetery. From the end of the 14th century, the dance of death was also the motif for the “Black Death”, the plague. The most unusual and shocking aspect of the Dance of Death motif for contemporaries was the combination of the theme of death with dance - one of the most vital expressions of the joy and affirmation of life. This macabre combination of opposites will not have failed to have a moral effect.

Tödlein, Southern Germany, 2nd half of the 18th century, softwood. Ever since the scythe became established as an agricultural tool for mowing meadows in the 14th century, the symbol of death as a reaper has existed. Here, however, Death presents himself not only as a reaper, but also as a minstrel and gravedigger who, with a light hand and theatrical, prancing movement theatrically prancing movement has lifted a heavy grave slab for his victim. The spindly finger bones of his outstretched right hand simultaneously clasp the shaft of the scythe, as if he wanted to play a stringed instrument for the last dance.

Tödlein, Southern Germany, 2nd half of the 18th century, softwood. Ever since the scythe became established as an agricultural tool for mowing meadows in the 14th century, the symbol of death as a reaper has existed. Here, however, Death presents himself not only as a reaper, but also as a minstrel and gravedigger who, with a light hand and theatrical, prancing movement theatrically prancing movement has lifted a heavy grave slab for his victim. The spindly finger bones of his outstretched right hand simultaneously clasp the shaft of the scythe, as if he wanted to play a stringed instrument for the last dance.

Model of the Zizenhausen danse macabre, Zizenhausen, Anton Sohn, 1822/1823, casting, 19th cent., fired clay, cast using a mould, polychrome. Anton Sohn was a church painter who became famous for his so-called Zizenhausen terracottas. These here are a model of the Basel Dance of Death, a picture which was painted on the inside of the cemetery wall near the Predigerkirche in Basel in the late Middle Ages and depicted the Dance of Death. The painting is a memento mori, reminding that death snatches everyone from life, regardless of their status, expressed by the different scenes of figures.

Model of the Zizenhausen danse macabre, Zizenhausen, Anton Sohn, 1822/1823, casting, 19th cent., fired clay, cast using a mould, polychrome. Anton Sohn was a church painter who became famous for his so-called Zizenhausen terracottas. These here are a model of the Basel Dance of Death, a picture which was painted on the inside of the cemetery wall near the Predigerkirche in Basel in the late Middle Ages and depicted the Dance of Death. The painting is a memento mori, reminding that death snatches everyone from life, regardless of their status, expressed by the different scenes of figures.

Paternoster (Rosary), Spanish-Mexican, last quarter of the 16th cent., Walnut, hornbeam, traces of gilding, hummingbird feathers, silver, enamel. The prayer cord consists of seven skulls that can be opened. When open, the small skull halves reveal micro-carvings. The reliefs depict events from the childhood and passion of Christ as well as the hil. Jerome and Anthony of Padua.

Paternoster (Rosary), Spanish-Mexican, last quarter of the 16th cent., Walnut, hornbeam, traces of gilding, hummingbird feathers, silver, enamel. The prayer cord consists of seven skulls that can be opened. When open, the small skull halves reveal micro-carvings. The reliefs depict events from the childhood and passion of Christ as well as the hil. Jerome and Anthony of Padua.

Job in misery, Upper Rhine or Swabia, c. 1500, Wood. The small-format carving depicts Job. His trust in God was put to the test when he lost his entire fortune and experienced the death of his children. Finally, he himself fell ill and was afflicted with leprosy. Job sits sorrowfully on a pile of stones and supports his head with his left hand. The potsherd in his right hand is used to scrape the wounds on his body, which is only covered by a loincloth. Due to the reworked surface, it is no longer clear whether the stigmata of the leprosy were once visible on the naked body. The type of representation of the figure is reminiscent of the iconography of the resting Christ, which shows the Son of God waiting to be crucified. As Job humbly endured all the blows of fate, he became a symbol of a godly way of life. As a model for a virtuous life, the expressive carving most likely served as a means of personal devotion. At the same time, it embodies existential thoughts about the vulnerability of human existence, which already make a humanistic attitude palpable.

Job in misery, Upper Rhine or Swabia, c. 1500, Wood. The small-format carving depicts Job. His trust in God was put to the test when he lost his entire fortune and experienced the death of his children. Finally, he himself fell ill and was afflicted with leprosy. Job sits sorrowfully on a pile of stones and supports his head with his left hand. The potsherd in his right hand is used to scrape the wounds on his body, which is only covered by a loincloth. Due to the reworked surface, it is no longer clear whether the stigmata of the leprosy were once visible on the naked body. The type of representation of the figure is reminiscent of the iconography of the resting Christ, which shows the Son of God waiting to be crucified. As Job humbly endured all the blows of fate, he became a symbol of a godly way of life. As a model for a virtuous life, the expressive carving most likely served as a means of personal devotion. At the same time, it embodies existential thoughts about the vulnerability of human existence, which already make a humanistic attitude palpable.

One of the eight prophets from Cologne City Hall, Cologne, c. 1430-1440, oak, polychrome painted. The wooden figures come from the historic town hall of the city of Cologne. The prophets were created for the entrance area to the town hall in the Gothic council tower, which was built as a visible symbol following the political upheavals in Cologne shortly before 1400, when the rule of the patricians was replaced by a council formed by the gaffs. They were placed on a staircase that the councillors passed on their way to the council chamber and presented moral guidelines for good governance on the banners.

One of the eight prophets from Cologne City Hall, Cologne, c. 1430-1440, oak, polychrome painted. The wooden figures come from the historic town hall of the city of Cologne. The prophets were created for the entrance area to the town hall in the Gothic council tower, which was built as a visible symbol following the political upheavals in Cologne shortly before 1400, when the rule of the patricians was replaced by a council formed by the gaffs. They were placed on a staircase that the councillors passed on their way to the council chamber and presented moral guidelines for good governance on the banners.

Double figure: The Virgin Mary and Child and St. Anne with the Virgin and Child (not visible in this photograph), Master of Osnabrück, c. 1520, Oak.This figure is prominently displayed in the former church hall.

Double figure: The Virgin Mary and Child and St. Anne with the Virgin and Child (not visible in this photograph), Master of Osnabrück, c. 1520, Oak.This figure is prominently displayed in the former church hall.

Prayer bead in the shape of the virgin Mary’s head, Germany, (Netherlands?), 16th cent., Fruit wood. A rare example of a carved prayer nut in the shape of a woman’s head and an important example of microcarving from fruit tree wood in northern Europe in the 16th century. The head is carved from two pieces joined together by a wooden hinge and a metal pin. When the clasp is unhooked, the sculpture opens to reveal two relief carvings: the Carrying of the Cross (in the upper half) and the Crucifixion (in the lower half). The intention is to arouse compassion in those who open the prayer nut and look at its contents.

Prayer bead in the shape of the virgin Mary’s head, Germany, (Netherlands?), 16th cent., Fruit wood. A rare example of a carved prayer nut in the shape of a woman’s head and an important example of microcarving from fruit tree wood in northern Europe in the 16th century. The head is carved from two pieces joined together by a wooden hinge and a metal pin. When the clasp is unhooked, the sculpture opens to reveal two relief carvings: the Carrying of the Cross (in the upper half) and the Crucifixion (in the lower half). The intention is to arouse compassion in those who open the prayer nut and look at its contents.

St. James the Greater and St. James the Less from the Altar of the Poor Clares in Cologne Cathedral, Cologne, c. 1360. The two figures originate from the so-called Poor Clares altar, which was created in the mid-14th century for the Poor Clares monastery in Cologne. When the Poor Clares monastery was secularized at the beginning of the 19th century and the monastery church was demolished shortly afterwards, the altarpiece was transferred to the cathedral before 1811, where it is now displayed in the north aisle. The reredos is the earliest surviving example of a carved altarpiece with a double pair of wings. The box and the insides of the inner wings are decorated with carved figures and bust reliquaries. The outer sides of the inner pair of wings and the outer wings bear paintings on wood and canvas. Depending on the opening of the altar, a different pictorial program is displayed for certain church feast days. The two figures of St. James are part of a cycle of apostles on the altar.

St. James the Greater and St. James the Less from the Altar of the Poor Clares in Cologne Cathedral, Cologne, c. 1360. The two figures originate from the so-called Poor Clares altar, which was created in the mid-14th century for the Poor Clares monastery in Cologne. When the Poor Clares monastery was secularized at the beginning of the 19th century and the monastery church was demolished shortly afterwards, the altarpiece was transferred to the cathedral before 1811, where it is now displayed in the north aisle. The reredos is the earliest surviving example of a carved altarpiece with a double pair of wings. The box and the insides of the inner wings are decorated with carved figures and bust reliquaries. The outer sides of the inner pair of wings and the outer wings bear paintings on wood and canvas. Depending on the opening of the altar, a different pictorial program is displayed for certain church feast days. The two figures of St. James are part of a cycle of apostles on the altar.

Christ with the winnowing fan separates the wheat from the chaff, Cologne, 1150-1160, Copper, repoussé and gilded, soldered onto a mandorla-shaped copper sheet. Christ sits on a magnificently decorated throne with his arms outstretched with power, his feet on a round structure that symbolizes the earth. A scroll swings out of his right hand in front of him, saying: “For in his hand is the shovel and he will cleanse his threshing floor.” Therefore, the lost object in the other hand can be completed as a grain shovel, which used to be used to separate the wheat from the chaff by throwing it up after threshing. The gleaming golden image therefore refers to the divine ruler of heaven, who will judge mankind at the end of time.

Christ with the winnowing fan separates the wheat from the chaff, Cologne, 1150-1160, Copper, repoussé and gilded, soldered onto a mandorla-shaped copper sheet. Christ sits on a magnificently decorated throne with his arms outstretched with power, his feet on a round structure that symbolizes the earth. A scroll swings out of his right hand in front of him, saying: “For in his hand is the shovel and he will cleanse his threshing floor.” Therefore, the lost object in the other hand can be completed as a grain shovel, which used to be used to separate the wheat from the chaff by throwing it up after threshing. The gleaming golden image therefore refers to the divine ruler of heaven, who will judge mankind at the end of time.

One of two angels as deacons with banderoles, Cologne, c. 1530 Lime, polychromy. As messengers of God, these angels hold Latin banners with biblical quotations calling for confession of sin and repentance.

One of two angels as deacons with banderoles, Cologne, c. 1530 Lime, polychromy. As messengers of God, these angels hold Latin banners with biblical quotations calling for confession of sin and repentance.

The Foot-Washing, Master of Viborg, Antwerp, c. 1515-1520, Oak, polychromy.

The Foot-Washing, Master of Viborg, Antwerp, c. 1515-1520, Oak, polychromy.

Corbel bust with the Parler coat of arms, Cologne, Workshop of the Parler, c. 1390 Limestone, renewed polychromy. The “beautiful Parler woman” is a wonderful work of art by the widely ramified Parler family of artists, who had a significant influence on European sculpture and architecture from the Rhineland to Bohemia in the second half of the 14th century. This limestone bust is actually a functional architectural element for supporting a load.

Corbel bust with the Parler coat of arms, Cologne, Workshop of the Parler, c. 1390 Limestone, renewed polychromy. The “beautiful Parler woman” is a wonderful work of art by the widely ramified Parler family of artists, who had a significant influence on European sculpture and architecture from the Rhineland to Bohemia in the second half of the 14th century. This limestone bust is actually a functional architectural element for supporting a load.

Host vessel (Pyxis) with monograms of Christ (“IHS” and “XPS”), Limoges, c. 1200-1210, Gilt copper with enamel. A “pyx” is a small round container. In addition to tabernacles and containers in the shape of a dove, pyxes are among the various types of enameled host containers that were mass-produced in the French city of Limoges in the 13th century. This pyx shows the typical Limousin shape with a cylindrical vessel and a conical lid crowned with a cross. Pit enamel with a tendril pattern on a blue background decorates the vessel and lid. The tendril spiral encircles blossoms in white, light blue, red and turquoise as well as the Christ monograms IHS and XPS.

Host vessel (Pyxis) with monograms of Christ (“IHS” and “XPS”), Limoges, c. 1200-1210, Gilt copper with enamel. A “pyx” is a small round container. In addition to tabernacles and containers in the shape of a dove, pyxes are among the various types of enameled host containers that were mass-produced in the French city of Limoges in the 13th century. This pyx shows the typical Limousin shape with a cylindrical vessel and a conical lid crowned with a cross. Pit enamel with a tendril pattern on a blue background decorates the vessel and lid. The tendril spiral encircles blossoms in white, light blue, red and turquoise as well as the Christ monograms IHS and XPS.

Cologne Missal (Missale Novum Diocesis Coloniensis), Print: Paris, Nicolas Prévost (printing house of Wolfgang Hopyl), 8 November 1525 for Arnold Birckman, Cologne Paper, coloured, Latin. One of the first printed missals in Cologne. The missal contains the texts of the Mass for the entire liturgical year.

Cologne Missal (Missale Novum Diocesis Coloniensis), Print: Paris, Nicolas Prévost (printing house of Wolfgang Hopyl), 8 November 1525 for Arnold Birckman, Cologne Paper, coloured, Latin. One of the first printed missals in Cologne. The missal contains the texts of the Mass for the entire liturgical year.

Christ Enthroned, plaque from a liturgical object, Limoges, 12th cent., Bronze with enamel, turquoises.

Christ Enthroned, plaque from a liturgical object, Limoges, 12th cent., Bronze with enamel, turquoises.

Head of an Abbot’s Croisier from the Cistercian Abbey of Bebenhausen, Depicting the Embracing of St. Bernard of Clairvaux by Crucified Christ, Probably southwest Germany, c. 1555, Copper, gilded and partially silvered. The crook once crowned the abbot’s staff of the Bebenhausen abbot Sebastian Lutz (1549-1560) and shows the so-called Bernhardsminne, also known as Amplexus Bernardi (embrace of St. Bernard), in a fully sculpted depiction. According to legend, St. Bernard (1090-1153), abbot of the Cistercian abbey of Clairvaux, was embraced by the crucified man as he prayed in front of a crucifix. The amplexus embodies Bernhard’s deep passionate piety and therefore became a very popular iconographic motif in Cistercian monasteries. By choosing this motif for the crook of his abbot’s crook, Sebastian Lutz made Bernard a spiritual role model for himself and for the monastic community under his care. The depiction of the embrace is characterized by great intimacy. With his arms detached from the crossbeam, Christ bends down to Bernhard and places his hands on the saint’s shoulders. With his hands raised in prayer, he looks up at Christ. The artfully curved bend of the crook surrounds the group of figures in the manner of a bracket and thus reinforces the impression of intimate agreement between Bernhard and Christ.

Head of an Abbot’s Croisier from the Cistercian Abbey of Bebenhausen, Depicting the Embracing of St. Bernard of Clairvaux by Crucified Christ, Probably southwest Germany, c. 1555, Copper, gilded and partially silvered. The crook once crowned the abbot’s staff of the Bebenhausen abbot Sebastian Lutz (1549-1560) and shows the so-called Bernhardsminne, also known as Amplexus Bernardi (embrace of St. Bernard), in a fully sculpted depiction. According to legend, St. Bernard (1090-1153), abbot of the Cistercian abbey of Clairvaux, was embraced by the crucified man as he prayed in front of a crucifix. The amplexus embodies Bernhard’s deep passionate piety and therefore became a very popular iconographic motif in Cistercian monasteries. By choosing this motif for the crook of his abbot’s crook, Sebastian Lutz made Bernard a spiritual role model for himself and for the monastic community under his care. The depiction of the embrace is characterized by great intimacy. With his arms detached from the crossbeam, Christ bends down to Bernhard and places his hands on the saint’s shoulders. With his hands raised in prayer, he looks up at Christ. The artfully curved bend of the crook surrounds the group of figures in the manner of a bracket and thus reinforces the impression of intimate agreement between Bernhard and Christ.

Head of Christ, Cologne, late 10th cent. / 1st third 11th cent., Shelly limestone, Cologne, St. Pantaleon.

Head of Christ, Cologne, late 10th cent. / 1st third 11th cent., Shelly limestone, Cologne, St. Pantaleon.

Two Cherubim, Cologne, c. 1230 Oak, polychromy. In the Middle Ages, the cherubim belonged to the highest orders of angels and were considered to be particularly close to the throne of God. Two pairs of wings that cross in front of the bodies of these cherubim make it look as though they are wrapped in a robe of feathers. Probably a third pair of wings was crossed over their backs. Although oxidised to black today, the polychrome layer of gold-lacquered silver once gave the figures a sumptuous aspect reminiscent of works of goldsmith’s art. The plumage and the winged wheels on which the two figures stand are motifs that already feature in the angel figures on the shrine of St. Maurinus. Perhaps these cherubim can also be imagined as guardian figures on either side of a shrine.

Two Cherubim, Cologne, c. 1230 Oak, polychromy. In the Middle Ages, the cherubim belonged to the highest orders of angels and were considered to be particularly close to the throne of God. Two pairs of wings that cross in front of the bodies of these cherubim make it look as though they are wrapped in a robe of feathers. Probably a third pair of wings was crossed over their backs. Although oxidised to black today, the polychrome layer of gold-lacquered silver once gave the figures a sumptuous aspect reminiscent of works of goldsmith’s art. The plumage and the winged wheels on which the two figures stand are motifs that already feature in the angel figures on the shrine of St. Maurinus. Perhaps these cherubim can also be imagined as guardian figures on either side of a shrine.

Neuerburg Crucifix, 2nd half of the 11th cent., Willow (corpus), poplar (arms), polychromy.

Neuerburg Crucifix, 2nd half of the 11th cent., Willow (corpus), poplar (arms), polychromy.

Our Lady of Sorrows from a Triumphal Crucifixion, Estern Alps, c. 1220-1230, Beech, polychrome. The mourning Mary was once part of a triumphal cross group. Triumphal cross groups were part of the furnishing repertoire of high-ranking churches. They were placed on a wooden triumphal beam in the choir arch at the interface between the choir and the laity area and dominated the interior of the church, visible from afar. As a sign of mourning, Mary has gently placed her left hand on the cheek of the bowed head.

Our Lady of Sorrows from a Triumphal Crucifixion, Estern Alps, c. 1220-1230, Beech, polychrome. The mourning Mary was once part of a triumphal cross group. Triumphal cross groups were part of the furnishing repertoire of high-ranking churches. They were placed on a wooden triumphal beam in the choir arch at the interface between the choir and the laity area and dominated the interior of the church, visible from afar. As a sign of mourning, Mary has gently placed her left hand on the cheek of the bowed head.

Christ on an Ass for the Palm Sunday Procession from St. Kolumba in Cologne, Cologne, c. 1520, Lime and softwood (wagon), polychromy. A donkey stands on a mobile frame with four wheels, carrying the life-size figure of Christ sitting upright on her back. The dignified figure of Christ has raised his right hand in a gesture of blessing, while the position of his left hand seems to indicate that a palm branch could once be inserted here. Christ’s entry into Jerusalem was celebrated every year on Palm Sunday as the beginning of the Passion story. In contrast to many other wooden sculptures, which were part of the immovable, fixed furnishings of the church building, the palm branch was directly incorporated into the special church celebrations as a “moving sculpture”. Accompanied by a procession, the Palmeselchristus rolled through the town and into the church like a royal ruler. The faithful along the way scattered branches in front of the passing image. This custom, which may date back as far as 1000 years, was particularly popular in the late Middle Ages.

Christ on an Ass for the Palm Sunday Procession from St. Kolumba in Cologne, Cologne, c. 1520, Lime and softwood (wagon), polychromy. A donkey stands on a mobile frame with four wheels, carrying the life-size figure of Christ sitting upright on her back. The dignified figure of Christ has raised his right hand in a gesture of blessing, while the position of his left hand seems to indicate that a palm branch could once be inserted here. Christ’s entry into Jerusalem was celebrated every year on Palm Sunday as the beginning of the Passion story. In contrast to many other wooden sculptures, which were part of the immovable, fixed furnishings of the church building, the palm branch was directly incorporated into the special church celebrations as a “moving sculpture”. Accompanied by a procession, the Palmeselchristus rolled through the town and into the church like a royal ruler. The faithful along the way scattered branches in front of the passing image. This custom, which may date back as far as 1000 years, was particularly popular in the late Middle Ages.

The Infant Christ, Cologne, c. 1500 Walnut, polychromy. The emotional veneration of Mary and Jesus in the late Middle Ages produced figures such as this Christ Child, which emphasizes the human nature of the Son of God. At Christmas time, Christ children, often expensively dressed, were placed on the altars of collegiate and parish churches. The right hand of this figure is raised in a gesture of blessing, while in the left it holds a ball as a symbol of the world, whose redeemer it reveals itself to be.

The Infant Christ, Cologne, c. 1500 Walnut, polychromy. The emotional veneration of Mary and Jesus in the late Middle Ages produced figures such as this Christ Child, which emphasizes the human nature of the Son of God. At Christmas time, Christ children, often expensively dressed, were placed on the altars of collegiate and parish churches. The right hand of this figure is raised in a gesture of blessing, while in the left it holds a ball as a symbol of the world, whose redeemer it reveals itself to be.

Christ Child Cradle, Cologne, c. 1340-50, Oak, polychromy, gilding, parchment, pastiglia gesso. Christmas cradles existed long before our nativity scenes were invented. In nunneries, they have been used for practical meditation on the story of redemption since the 14th century. Little pictures of Jesus were swaddled and cradled, dainty little blankets were embroidered for them and songs were sung for them. The infant Jesus with the little dress and blanket for this Christ Child cradle have not survived. It is one of the oldest “devotional pieces of furniture” of this kind and was created in Cologne between 1340 and 1350. Tracery, pinnacles and crabs, which we know from large buildings, frame the golden gable fields. the golden pediments. They tell of the salvific death of Jesus on the cross and of the adoration of the Magi, who worshipped the child of Bethlehem as the Messiah.

Christ Child Cradle, Cologne, c. 1340-50, Oak, polychromy, gilding, parchment, pastiglia gesso. Christmas cradles existed long before our nativity scenes were invented. In nunneries, they have been used for practical meditation on the story of redemption since the 14th century. Little pictures of Jesus were swaddled and cradled, dainty little blankets were embroidered for them and songs were sung for them. The infant Jesus with the little dress and blanket for this Christ Child cradle have not survived. It is one of the oldest “devotional pieces of furniture” of this kind and was created in Cologne between 1340 and 1350. Tracery, pinnacles and crabs, which we know from large buildings, frame the golden gable fields. the golden pediments. They tell of the salvific death of Jesus on the cross and of the adoration of the Magi, who worshipped the child of Bethlehem as the Messiah.

Resurrection and Ascension of Christ, Cologne (?), early 15th cent., painting on ivory.

Resurrection and Ascension of Christ, Cologne (?), early 15th cent., painting on ivory.

Christ as the Man of Sorrows, South Germany (?), c. 1420-1430 Red-yellow clay, fired, polychromy. The first half of the 15th century was the heyday of medieval clay sculpture, after the material had not played a leading role in artistic production before 1400. Particularly in southern Germany - with independent centers on the Middle Rhine, in Upper and Lower Bavaria and in Franconia - clay sculptors partly took over the production of ecclesiastical furnishings, which had previously been made almost exclusively in stone. One example of this is the half-figure Christ as the Man of Sorrows. The countless drops of blood, either individually or as a bundle of drops, ornamentally cover the face and body.

Christ as the Man of Sorrows, South Germany (?), c. 1420-1430 Red-yellow clay, fired, polychromy. The first half of the 15th century was the heyday of medieval clay sculpture, after the material had not played a leading role in artistic production before 1400. Particularly in southern Germany - with independent centers on the Middle Rhine, in Upper and Lower Bavaria and in Franconia - clay sculptors partly took over the production of ecclesiastical furnishings, which had previously been made almost exclusively in stone. One example of this is the half-figure Christ as the Man of Sorrows. The countless drops of blood, either individually or as a bundle of drops, ornamentally cover the face and body.

Standing Christ as Man of Sorrows, Germany (Lower Rhine/ Cologne?), c. 1500 Silver, cast, chiselled, partially gilded, rubies.

Standing Christ as Man of Sorrows, Germany (Lower Rhine/ Cologne?), c. 1500 Silver, cast, chiselled, partially gilded, rubies.

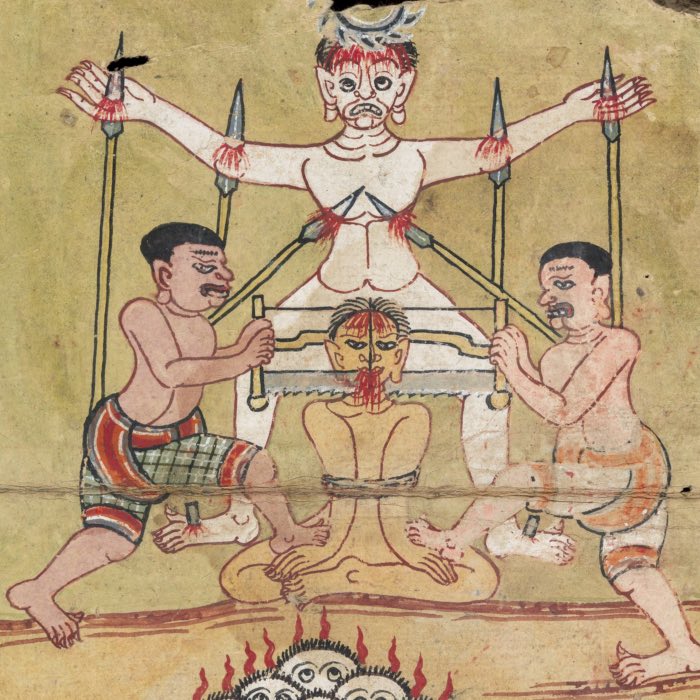

St. Vitus, Swabia, late 15th cent., Lime (?). St. Vitus, whose numerous torments are said to have included boiling in hot oil. With his hands folded in prayer in front of his chest, the youthful saint stands in the three-footed pot, clad only in a cloth around his hips. The message: sovereignly enduring his torture, he becomes an exemplary intercessor. The introverted facial expression is intensified by the striking design of the eye area. The veneration of St. Vitus only reached its peak in the late Middle Ages, particularly because he was one of the 14 emergency helpers, saints responsible for almost all the worries of daily life. Among other things, Vitus was invoked in cases of possession and St. Vitus’ dance (Huntington’s disease), fire and lightning, and he was also regarded as the patron saint of coppersmiths, lansquenets and farmers. Images showing St. Vitus in a cauldron were not created until the end of the 15th century, mainly in southern Germany. They were placed in smaller Vitus chapels or altarpieces.

St. Vitus, Swabia, late 15th cent., Lime (?). St. Vitus, whose numerous torments are said to have included boiling in hot oil. With his hands folded in prayer in front of his chest, the youthful saint stands in the three-footed pot, clad only in a cloth around his hips. The message: sovereignly enduring his torture, he becomes an exemplary intercessor. The introverted facial expression is intensified by the striking design of the eye area. The veneration of St. Vitus only reached its peak in the late Middle Ages, particularly because he was one of the 14 emergency helpers, saints responsible for almost all the worries of daily life. Among other things, Vitus was invoked in cases of possession and St. Vitus’ dance (Huntington’s disease), fire and lightning, and he was also regarded as the patron saint of coppersmiths, lansquenets and farmers. Images showing St. Vitus in a cauldron were not created until the end of the 15th century, mainly in southern Germany. They were placed in smaller Vitus chapels or altarpieces.

Christ as a prisoner, led in front of the people by Pontius Pilate (Ecce homo), South Germany, Ist half of the 17th cent., Boxwood. Standing on a small grass plinth in a fragile crotch position, the man visibly marked by his suffering almost as if his bony legs could hardly bear the weight of his maltreated body. The carver has depicted the emaciated body of Christ, clad only in a loosely wrapped loincloth, in an almost mannered exaggeration: The abdominal area is extremely drawn in and the ribcage, sternum, spine and shoulder blades are clearly visible beneath the taut surface of the skin. A network of veins covers the arms and legs. In contrast, the expressive head, adorned with a voluminous crown of thorns and raised above the left shoulder, appears almost oversized. The upward gaze from the deeply drilled pupils lends the perfectly composed work of art a captivating and at the same time frightening expression.

Christ as a prisoner, led in front of the people by Pontius Pilate (Ecce homo), South Germany, Ist half of the 17th cent., Boxwood. Standing on a small grass plinth in a fragile crotch position, the man visibly marked by his suffering almost as if his bony legs could hardly bear the weight of his maltreated body. The carver has depicted the emaciated body of Christ, clad only in a loosely wrapped loincloth, in an almost mannered exaggeration: The abdominal area is extremely drawn in and the ribcage, sternum, spine and shoulder blades are clearly visible beneath the taut surface of the skin. A network of veins covers the arms and legs. In contrast, the expressive head, adorned with a voluminous crown of thorns and raised above the left shoulder, appears almost oversized. The upward gaze from the deeply drilled pupils lends the perfectly composed work of art a captivating and at the same time frightening expression.

Ottonian Reliquary Casket, 1st half of the 11th cent., Ivory (lid), bone (long sides). The carved reliquary box depicts scenes from the life of Christ and John the Baptist in unusual iconography, based on the accounts in the Gospel of Luke. The narrative begins with the announcement of John’s birth to Zechariah (begins on one of the roof slopes). The story continues on both long sides. The birth of Christ is depicted in the middle under an arch; this scene is characterized by an unusually large depiction of the Christ child in the manger. It is flanked by Joseph, who points to the events with his left hand, and by the Visitation. As a counterpart to this, the other long side is entirely dedicated to the scene of the crucifixion. A striking feature of this depiction is the lack of a cross behind the crucified man. Longinus and Stephaton stand on either side of Christ and are depicted on a smaller scale. Mary and John express their grief in traditional gestures, while the personifications of Sol and Luna hover above the scene. Finally, the Ascension of Christ is depicted on the second roof surface. Christ stands in the center with expressively outstretched arms; the mighty hand of God, which forms the center of the Annunciation to Zechariah on the opposite roof slope, refers to him. The two scenes thus merge compositionally and close the circle of the narrative. The casket most likely once contained precious relics, probably a piece of Christ’s diaper and a piece of Mary’s robe.

Ottonian Reliquary Casket, 1st half of the 11th cent., Ivory (lid), bone (long sides). The carved reliquary box depicts scenes from the life of Christ and John the Baptist in unusual iconography, based on the accounts in the Gospel of Luke. The narrative begins with the announcement of John’s birth to Zechariah (begins on one of the roof slopes). The story continues on both long sides. The birth of Christ is depicted in the middle under an arch; this scene is characterized by an unusually large depiction of the Christ child in the manger. It is flanked by Joseph, who points to the events with his left hand, and by the Visitation. As a counterpart to this, the other long side is entirely dedicated to the scene of the crucifixion. A striking feature of this depiction is the lack of a cross behind the crucified man. Longinus and Stephaton stand on either side of Christ and are depicted on a smaller scale. Mary and John express their grief in traditional gestures, while the personifications of Sol and Luna hover above the scene. Finally, the Ascension of Christ is depicted on the second roof surface. Christ stands in the center with expressively outstretched arms; the mighty hand of God, which forms the center of the Annunciation to Zechariah on the opposite roof slope, refers to him. The two scenes thus merge compositionally and close the circle of the narrative. The casket most likely once contained precious relics, probably a piece of Christ’s diaper and a piece of Mary’s robe.

Head of a Holy Bishop, Cologne, c. 1160-80, Oak, polychromy. This expressive head with its large, almond-shaped eyes has only survived as a fragment. On the basis of its headdress, it is assumed to have been the representation of a bishop: the pointed cap he wears is a mitre. It was probably crafted in the same carving workshop in Cologne that is thought to have produced several other sculptures that have survived from this period.

Head of a Holy Bishop, Cologne, c. 1160-80, Oak, polychromy. This expressive head with its large, almond-shaped eyes has only survived as a fragment. On the basis of its headdress, it is assumed to have been the representation of a bishop: the pointed cap he wears is a mitre. It was probably crafted in the same carving workshop in Cologne that is thought to have produced several other sculptures that have survived from this period.

St. John from the Triumphal Crucifixion from Sonnenburg, Puster Valley (South Tyrol), late 12th cent., Stone pine, polychrome.

St. John from the Triumphal Crucifixion from Sonnenburg, Puster Valley (South Tyrol), late 12th cent., Stone pine, polychrome.

Christ on the Cross (Crucifixus dolorosus), Cologne, c. 1390-1400, Walnut, beech (Cross).

Christ on the Cross (Crucifixus dolorosus), Cologne, c. 1390-1400, Walnut, beech (Cross).

Shrine with scenes of the Passion (detail), predella of an altarpiece Kalkar, c. 1530-1540, Oak.

Shrine with scenes of the Passion (detail), predella of an altarpiece Kalkar, c. 1530-1540, Oak.

Adoration of the Magi (detail), Workshop of Arnt Beeldesnider, с. 1480-90, Oak, additions in hardwood, visible polychromy 19th cent. over traces of earlier layers.

Adoration of the Magi (detail), Workshop of Arnt Beeldesnider, с. 1480-90, Oak, additions in hardwood, visible polychromy 19th cent. over traces of earlier layers.

St. Dorothy, Cologne, Master Tilman, c. 1500, Beechwood, polychromy.

St. Dorothy, Cologne, Master Tilman, c. 1500, Beechwood, polychromy.

Casting mould for a cross and an amulet, Byzantine Empire, 12th-14th cent., Greenstone (slate). Eight different pendants, presumably made of lead, could be cast in this half of the cast model. The Christian pendant cross and the Greek inscriptions around the round amulet point to the Byzantine Empire as the place of origin; stylistic comparisons allow a dating to the 12th-14th centuries.

Casting mould for a cross and an amulet, Byzantine Empire, 12th-14th cent., Greenstone (slate). Eight different pendants, presumably made of lead, could be cast in this half of the cast model. The Christian pendant cross and the Greek inscriptions around the round amulet point to the Byzantine Empire as the place of origin; stylistic comparisons allow a dating to the 12th-14th centuries.

Male figure as candleholder (Acolyte), Byzantine Empire, 6th cent., Cast bronze, traces of gilding. The two spikes were used to attach the candles.

Male figure as candleholder (Acolyte), Byzantine Empire, 6th cent., Cast bronze, traces of gilding. The two spikes were used to attach the candles.

Romanesque Bronze Figures of Christ on the Cross.

Romanesque Bronze Figures of Christ on the Cross.

John the Evangelist, Cologne, c. 1330-1340, Walnut, polychromy.

John the Evangelist, Cologne, c. 1330-1340, Walnut, polychromy.

Madonna on the Wide Throne, Cologne, c. 1270 Oak, polychrome.

Madonna on the Wide Throne, Cologne, c. 1270 Oak, polychrome.

Mourning Virgin Mary from the high altar of the Liebfrauenkirche in Oberwesel, Middle Rhine, c. 1360-70 Oak, polychromy.

Mourning Virgin Mary from the high altar of the Liebfrauenkirche in Oberwesel, Middle Rhine, c. 1360-70 Oak, polychromy.

So-called Kendenich Madonna, Cologne, c. 1270-1280, Walnut, oak (back-board), polychrome.

So-called Kendenich Madonna, Cologne, c. 1270-1280, Walnut, oak (back-board), polychrome.

Madonna Enthroned with the depiction of a praying Poor Clare on its base, Cologne, ca. 1340, Walnut, polychromy; figure of the infant Jesus and crown lost. The high-quality Virgin Mary from Cologne sits on a broadly supported throne bench with a profiled plinth area. Her slightly shifted body position to the right and the raised left arm indicate the position of the (now missing) Christ Child. A crown and the only fragmentarily preserved sceptre (both not on display) distinguished her as the Queen of Heaven. There is a (now empty) reliquary compartment on the back.

Madonna Enthroned with the depiction of a praying Poor Clare on its base, Cologne, ca. 1340, Walnut, polychromy; figure of the infant Jesus and crown lost. The high-quality Virgin Mary from Cologne sits on a broadly supported throne bench with a profiled plinth area. Her slightly shifted body position to the right and the raised left arm indicate the position of the (now missing) Christ Child. A crown and the only fragmentarily preserved sceptre (both not on display) distinguished her as the Queen of Heaven. There is a (now empty) reliquary compartment on the back.

Sculptures from the high altar in Cologne Cathedral, Cologne, c. 1310, white marble with traces of gilding.

Sculptures from the high altar in Cologne Cathedral, Cologne, c. 1310, white marble with traces of gilding.

Reliquary, Lower Saxony, 2nd half of the 12th cent., Bronze, copper, gilded, rock crystal, vernis brun, oak core.

Reliquary, Lower Saxony, 2nd half of the 12th cent., Bronze, copper, gilded, rock crystal, vernis brun, oak core.

Conclusion

In my opinion, the Schnütgen Museum offers a unique perspective on medieval art, separating it from its traditional religious context and allowing for a new appreciation of its artistic value. The museum not only preserves these artworks but also provides an educational and insightful experience into the Middle Ages. And with its unique exhbition design, it allows for a very personal and intimate experience with the artworks.

References and further reading

- Manuela Beer, Moritz Woelk, Museum Schnütgen - Handbuch zur Sammlung, 2018, Verlag n/a, ISBN: 9783777428932

- Museum Schnütgen, Das Mittelalter in 111 Meisterwerken aus dem Museum Schnütgen Köln, 2003, Verlag n/a, ISBN: 9783774303416

- Ulrike Bergmann, Schnütgen-Museum: Die Holzskulpturen des Mittelalters (1000-1400), 1989, Hrsg.: Anton Legner, Druckerei Locher GmbH, 5000 Köln 51

- Reinhard Karrenbrock, Schnütgen-Museum: Die Holzskulpturen des Mittelalters II. (1400-1540), 2001, Hrsg.: Hiltrud Westermann-Angerhausen

comments