A Zen-Buddhist interpretation of the ‘Kölsches Grundgesetz’

I recently discoveredꜛ the small booklet “Dao De Colonia – Das Kölsche Grundgesetz und sein daoistisches Geheimnis” by Michael Wittschier, who interpreted the so-called “Kölsches Grundgesetzꜛ” (lit. “Cologne Basic Law”) in a Daoist way. Daoism is a philosophical tradition of Chinese origin which emphasizes living in harmony with the Dào (or Tao; Chinese, 道), a term that can be translated as “the way”, “the path”, or “the way of nature”. Wittschier’s interpretation is a very interesting read and I couldn’t resist to buy the booklet. However, I also thought that it would by an interesting experiment to interpret the “Kölsches Grundgesetz” in a Zen-Buddhist way. So, here we go.

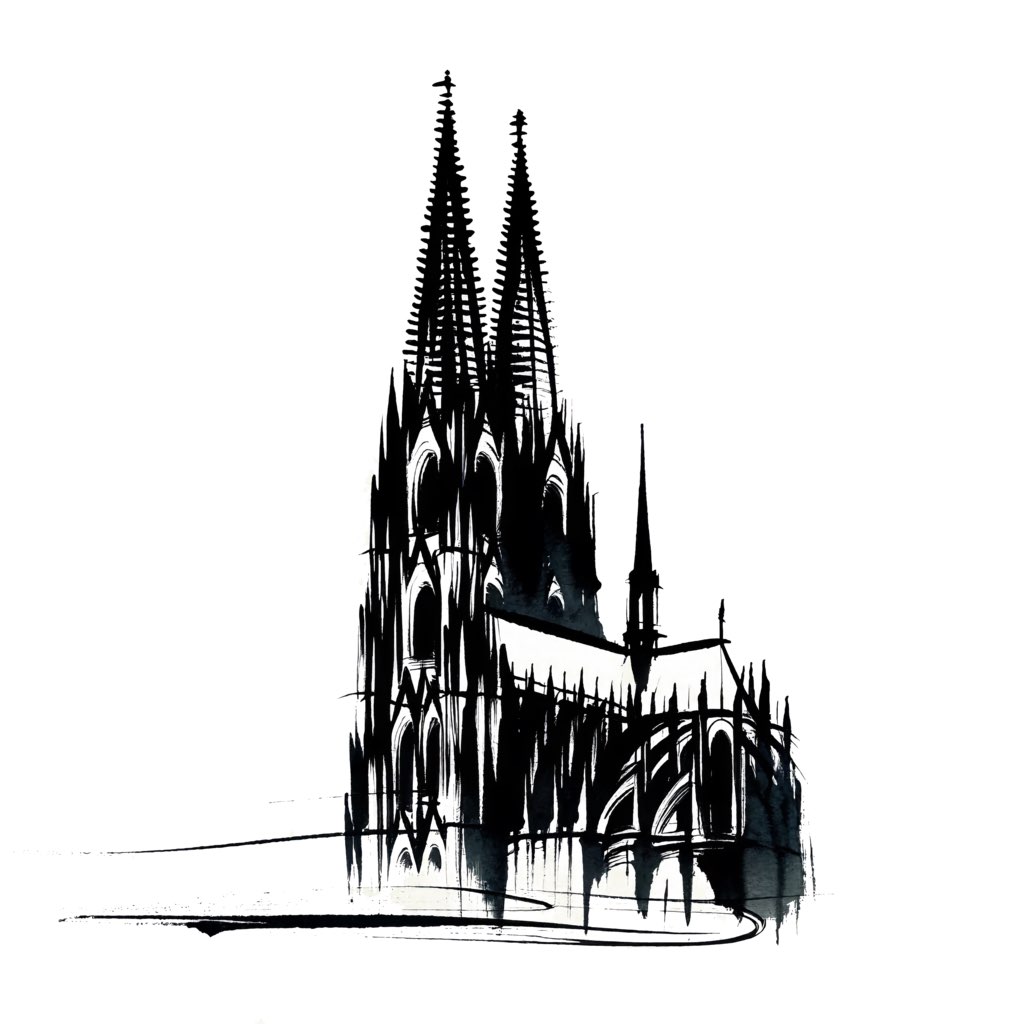

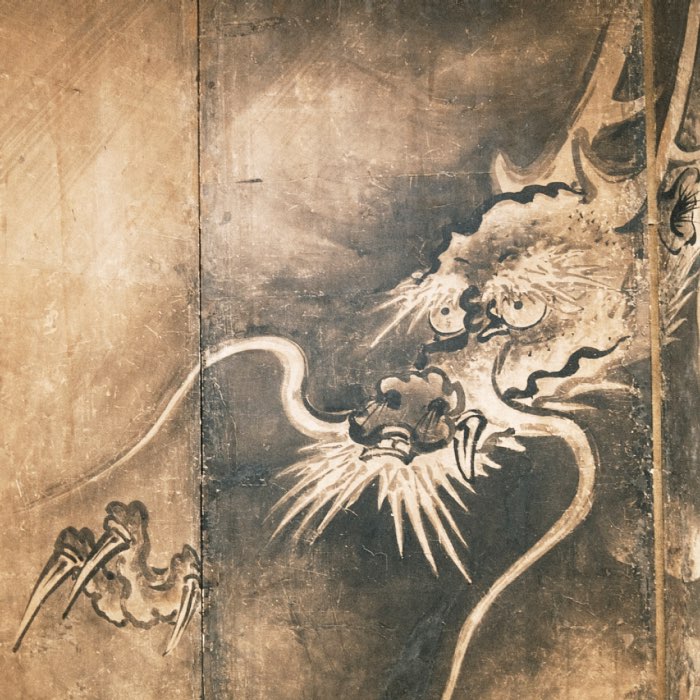

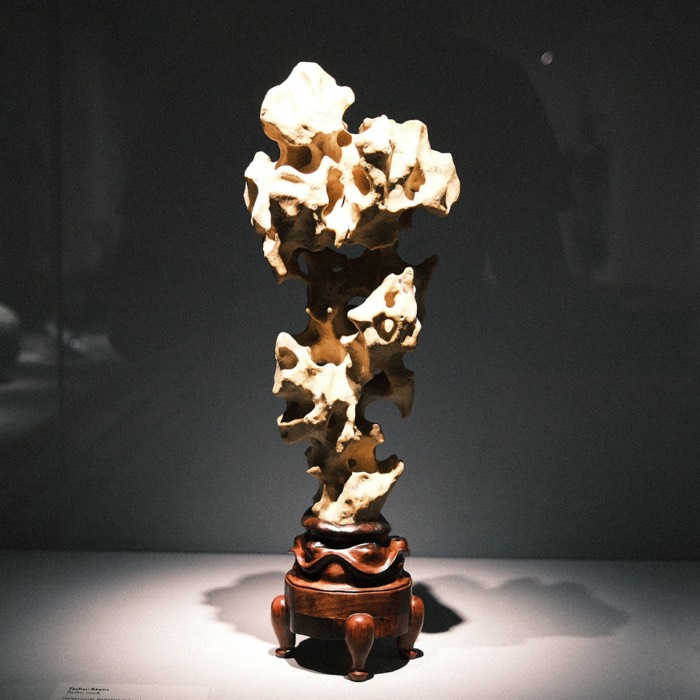

Zen op Kölsch – A Zen-Buddhist interpretation of the ‘Kölsch Grundgesetz’. Image created with DALL-E.

Zen op Kölsch – A Zen-Buddhist interpretation of the ‘Kölsch Grundgesetz’. Image created with DALL-E.

The “Kölsches Grundgesetz”, also called the “Rheinisches Grundgesetz”, is a humorous set of eleven rules written in the local dialect called “Kölsch”, that are supposed to reflect the mentality of the people of Cologne and the Rhineland. They were published 2001 by the cabaret artist Konrad Beikircher. However, there are claims that the rules are much older, dating back to the 16th century.

1. Et es wie et es

It is what it is – Face the facts, you can’t change anything anyway.

Buddhist interpretation

In Buddhism, there’s a significant emphasis on accepting reality as it is. This rule echoes the concept of mindfulness, urging acceptance of things as they come without resistance.

Shinnyo

The deeper concept behind this interpretation is Shinnyo (Japanese, 真如) or Tathatā (Sanskrit, तथता), a core concept in Buddhism, which means “true suchness” or “true nature”. It is the idea that everything is as it should be, seeing things as they really are, without illusions or distortions. And that we should accept things as they are.

2. Et kütt wie et kütt

It comes as it comes – Accept the inevitable; there’s nothing you can do to change the course of events anyway.

Buddhist interpretation

This mirrors the Buddhist idea of non-attachment. The future is uncertain, and clinging to how things should be only causes suffering. It’s better to live in the moment and let the future unfold as it will.

Mujō

The deeper concept behind this interpretation is Mujō (Japanese, 無常) or Annica (Pali, अनिच्चा), which means “impermanence”, another core concept in Buddhism. It is the idea that all things are transient and constantly changing.

3. Et hätt noch immer jot jejange

It has always gone well – What went well yesterday will also work tomorrow.

Buddhist interpretation

This rule reflects faith in the universe and one’s resilience, akin to Buddhist teachings that encourage trust in the process of life and recognizing that even challenges contribute to growth.

Sha

The deeper concept behind this interpretation is Sha (Japanese, 捨) or upekṣā (Sanskrit, उपेक्षा), which means “equanimity” or “serenity”; the ability to accept the ups and downs of life with a calm and balanced attitude. It is the idea that we should accept the world as it is, without attachment or aversion. It is another core concept in Buddhism.

4. Wat fott es, es fott

What’s gone is gone – Don’t lament things and don’t mourn things long forgotten..

Buddhist interpretation

As the second rule, this aligns with the Buddhist teaching of impermanence. All things in life are transient, and clinging to the past can only lead to suffering. Letting go and living in the present is advocated.

5. Et bliev nix wie et wor

Nothing stays as it was – Be open to innovation.

Buddhist interpretation

This again resonates with the constant change in the universe. Embracing that everything is in flux and constantly changing leads to inner peace.

6. Kenne mer nit, bruche mer nit, fott domet

What we don’t know, we don’t need, away with it – Be critical when innovations get out of hand.

Buddhist interpretation

In Buddhism, this could be seen as a call for simplicity and reduction to essentials. Unnecessary clutter, whether material or mental, should be let go.

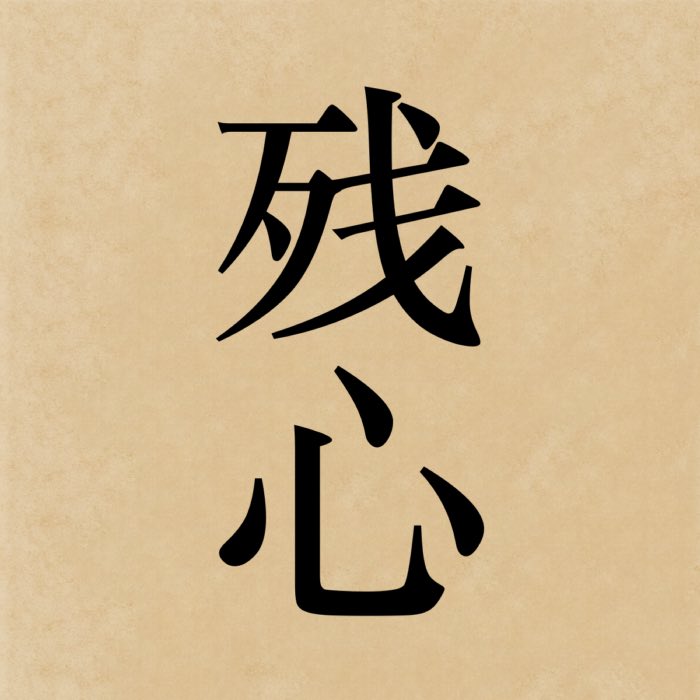

Zanshin

The deeper concept behind this interpretation is Zanshin (Japanese, 残心), which means “balanced mind” or “mind that remains immobile” and can be interpreted as “the mind with no remainder” or “vigilance”, “constant attention”. It is a state of attention and open awareness. Buddhism is about detaching oneself from the unimportant and concentrating on the essential.

Sati

There is no direct equivalent in Sanskrit, but Sati (सति), “mindfulness”, “awareness”, or “attention” could be considered the closest. It is the idea that we should be aware of our thoughts, feelings, and actions at all times.

Wabi Sabi

A further interpretation could be the Japanese concept of Wabi Sabi (侘寂), which means “rustic simplicity” (wabi, 侘) and “enjoy the imperfect” (sabi, 寂). It is an aesthetic concept for the perception of beauty as it is, which was introduced in the 16th century by the Japanese tea master and Zen monk Sen no Rikyū. It is the aesthetic of the imperfect and ephemeral, which is expressed, for example, in the asymmetry, roughness, irregularity, simplicity and economy of things. Through unpretentiousness and modesty, one demonstrates respect for the uniqueness of each object and phenomenon.

7. Wat wells de maache

What do you want to do – Resign yourself to your fate.

Buddhist interpretation

This rule may acknowledge the limits of our control, in line with Buddhist teachings that we have limited influence over the world and acceptance and serenity in the face of what we cannot change are crucial.

Wu Wei

The deeper concept behind this interpretation is Wu Wei (Chinese, 無為; in Japanese: Mu’i), which means “non-action”, “non-doing”, or “acting by not acting”. It is actually a Daoist concept, but it is also found in Buddhism. It is the idea that we should act in harmony with the natural flow of the universe, without forcing things.

8. Maach et jot, ävver nit zo off

Do it well, but not too often – Quality over quantity.

Buddhist interpretation

In Buddhism, this might be interpreted as a call for moderation and balance in life. It’s about showing commitment, but not in excess, to lead a harmonious life.

Chūdō

The deeper concept behind this interpretation is Chūdō (Japanese, 中道) or Madhyamā-pratipad (Sanskrit, मध्यमा प्रतिपद्), which means “middle way” or “middle path”. It is the idea that we should avoid extremes and find a balance between the two extremes; a balanced way of life that avoids extremes.

9. Wat soll dä Quatsch

What’s this nonsense – Always ask the universal question.

Buddhist interpretation

This could be seen as encouragement to focus on what’s essential and to free oneself from unnecessary worries and illusions, a central theme in Buddhism.

Kenshō

The deeper concept behind this interpretation is kenshō (Japanese, 見性) or Vipassanā (Pali, विपश्यना), which means “insight” or “clear seeing”. It is a sudden awakening and insight into one’s true nature; in Buddhism, often a moment in which one recognizes the non-substantiality of worries and problems, seeing things as they really are, without illusions or distortions. It is another core concept in Buddhism.

10. Drinkste eine met

Will you have a drink with me – Follow the commandment of hospitality.

Buddhist interpretation

This rule could reflect the importance of community and sharing in Buddhism. Sharing a drink (not necessarily alcohol; you could also drink and share tea) can be an act of connectedness and compassion.

Sangha

The deeper concept behind this interpretation the Sangha (Sanskrit, संघ) or sō (Japanese, 僧), which means “community” or “association”. It is the idea that we should surround ourselves with like-minded people who support us on our spiritual path. It is another core concept in Buddhism.

11. Do laachs de disch kapott

You’ll laugh yourself silly – Maintain a healthy attitude towards humor.

Buddhist interpretation

Buddhism often emphasizes the importance of joy and humor, even in difficult situations. This rule reminds us not to take life too seriously and to find joy wherever possible.

Karuna

There is actually no direct equivalent in Buddhism, but the concept of Karuna (Sanskrit, करुणा) or Kan (Japanese, 憐), which means “compassion”, “empathy”, or “pity”, could be considered the closest. It is the idea that we should be compassionate towards others – and ourselves. It is another core concept in Buddhism.

Hotei

Another interpretation could be Hotei (Japanese, 布袋), the “laughing Buddha”, who is often depicted with a big belly and a laughing face. He is a symbol of happiness, contentment, and abundance. He is also a symbol of generosity and giving, and he is often depicted with a sack full of gifts. Hotei is a manifestation of the Bodhisattva Maitreya, the Buddha of the future and great world teachers to come.

Conclusion

To my surprise, and despite the fact that it is a humorous set of rules, I found that the Kölsche Grundgesetz can indeed be interpreted in a Buddhist way. The above interpretations are just one of many possible ones. However, perhaps it inspires you to think about the Kölsche Grundgesetz in a new way. If you have any other ideas for interpretations or thoughts, feel free to share them in the comments below.

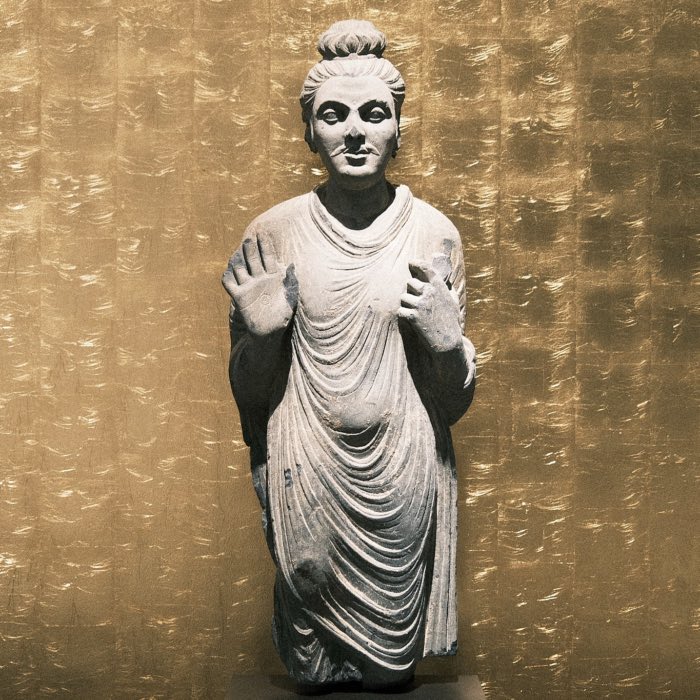

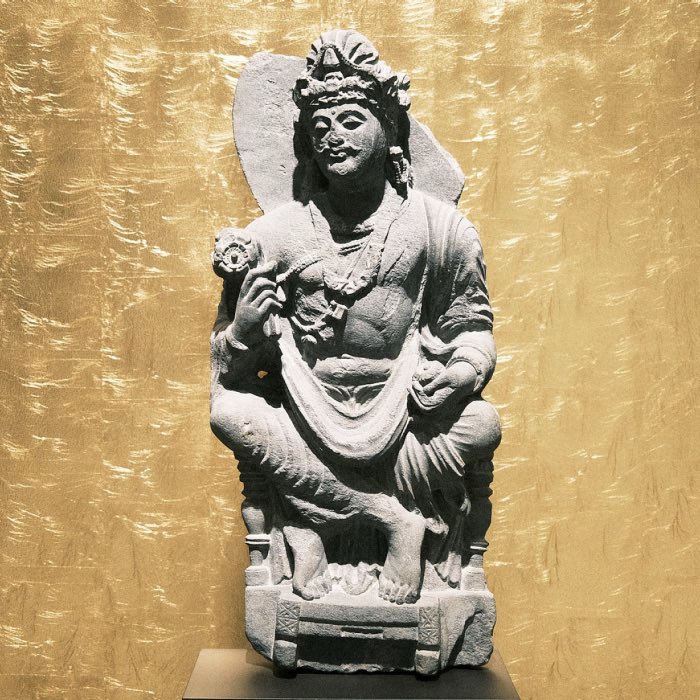

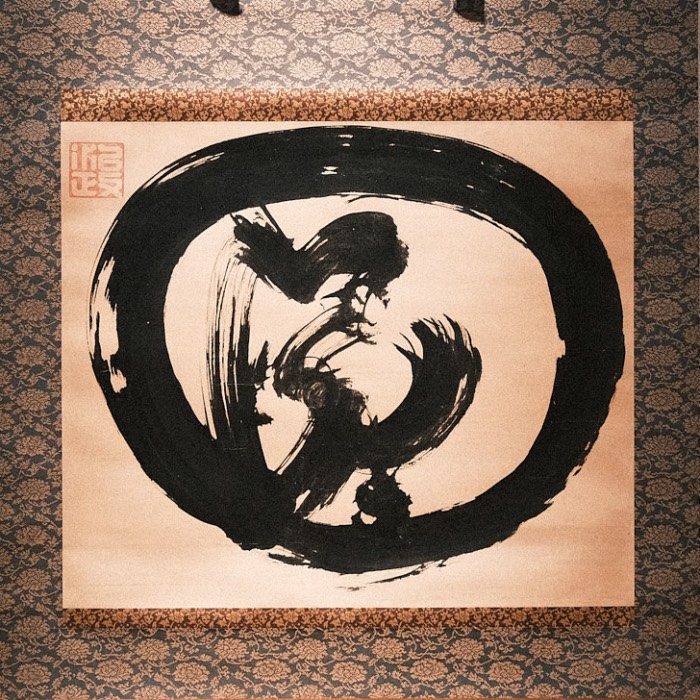

An alternative version of the cover image for this post, created with DALL-E.

An alternative version of the cover image for this post, created with DALL-E.

References and further reading

- Michael Wittschier, Dao De Colonia Das Kölsche Grundgesetz und sein daoistisches Geheimnis, 2023, Greven Verlag Köln, ISBN: 978-3-7743-0962-3

- Konrad Beikircher: Et kütt wie et kütt – Das Rheinische Grundgesetz, 2001, KiWi-Köln, ISBN: 978-3462035162

- Wikipedia article on the Kölsches Grundgesetzꜛ

comments