Collaboration with devils: The Catholic Church and totalitarian regimes in the 1930s

The Catholic Church’s relationship with totalitarian regimes during the 20th century reveals a complex interplay of pragmatism, institutional survival, and moral failure. Among the most controversial instances of this interaction is the Reichskonkordat (Reich Concordat), signed between the Vatican and Nazi Germany in 1933. This agreement, which lent a measure of legitimacy to Adolf Hitler’s regime, epitomizes the Church’s willingness to compromise with dictatorial powers to secure its institutional interests. However, this was not an isolated incident; the Vatican also reached similar accommodations with Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime in Italy and Francisco Franco’s Nationalist government in Spain. These alliances raise critical questions about the Church’s priorities and its complicity in enabling authoritarian rule.

The Reichskonkordat: A pivotal agreement with Nazi Germany

Historical context and motivations

The Reichskonkordat was signed on July 20, 1933, between the Holy See, represented by Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli (later Pope Pius XII), and Nazi Germany, represented by Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen. This agreement followed the Nazi seizure of power in January 1933 and came at a time when Hitler was consolidating his authoritarian control. For the Vatican, the concordat was a strategic decision aimed at securing the rights of the Catholic Church in Germany. It guaranteed the Church’s autonomy in spiritual, educational, and social matters, which had been eroded under the secularizing policies of the Weimar Republic.

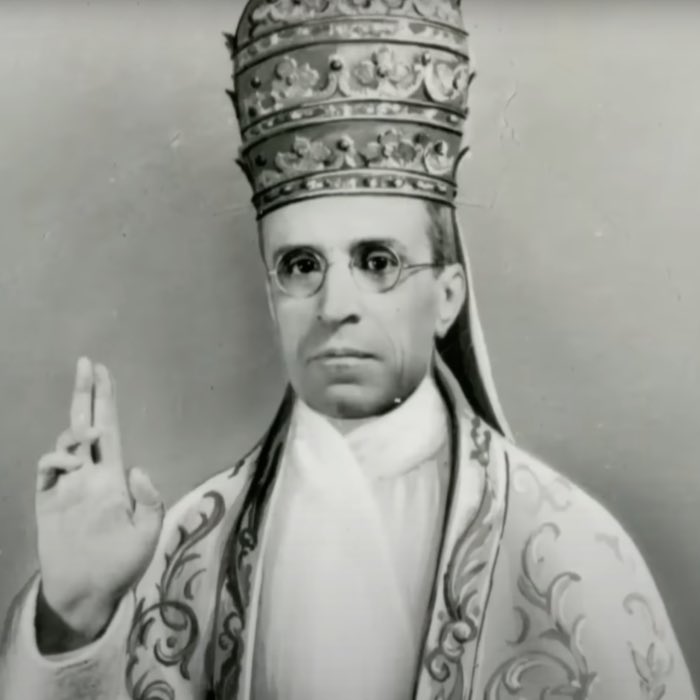

Left: Eugenio Pacelli, who signed the Reichskonkordat on behalf of the Vatican and later became Pope Pius XII. This image shows him around 1958, when he was already Pope. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) Right: Franz von Papen (1933), who signed the Reichskonkordat on behalf of the Nazi government. While being not a member of the NSDAP a that time, von Paper was an ultranationalist and a key figure in the rise of Hitler. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Vatican’s motivations for entering into this agreement were multifaceted:

- Institutional protection: The Church sought to safeguard its operations in Germany, including schools, youth organizations, and charitable activities, amid the rising tide of political instability.

- Fear of communism: The Vatican viewed communism, with its atheistic ideology, as a greater existential threat than fascism. Nazi Germany, with its vehement anti-communist stance, was seen as a potential ally against Soviet influence.

- A misguided belief in containment: Some Church officials believed that engaging with the Nazis would moderate their policies and curtail their excesses.

The signing of the Reichskonkordat on 20 July 1933 in Rome. From left to right: German prelate Ludwig Kaas, German Vice-Chancellor Franz von Papen, Secretary of Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs Giuseppe Pizzardo, Cardinal Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli, Alfredo Ottaviani, and member of Reichsministerium des Inneren (Home Office) Rudolf Buttmann. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Provisions of the Reichskonkordat

The agreement included several key provisions:

- The Church was granted freedom to administer its spiritual and educational missions.

- Clergy were exempted from military service and certain state obligations.

- Catholic organizations were allowed to operate, provided they refrained from political activity.

- Bishops were required to swear an oath of loyalty to the German state.

In practice, however, these concessions came at a significant cost. The Catholic Centre Party, one of the last bastions of democratic opposition to Hitler, was dissolved, effectively eliminating a major political counterweight to the Nazi regime. By signing the concordat, the Vatican also signaled to the international community a willingness to normalize relations with the Nazis, lending the regime a measure of moral credibility during its early consolidation of power.

Consequences and complicity

The Reichskonkordat quickly proved to be a hollow safeguard. The Nazis repeatedly violated its terms, suppressing Catholic publications, disbanding youth organizations, and persecuting clergy. While the Vatican occasionally protested these breaches, its overall response remained muted, prioritizing institutional preservation over active resistance. The agreement enabled the Nazis to claim a veneer of legitimacy while systematically dismantling opposition and perpetrating atrocities.

After the war

After World War II, the Reichskonkordat remained in effect, with Pope Pius XII emphasizing its preservation despite concerns from some bishops and skepticism from the Allied powers. The concordat ensured the Catholic Church’s return to its pre-war position, maintaining significant privileges within Germany.

In 1957, the Federal Constitutional Court ruled on a conflict regarding the concordat when Lower Saxony enacted a school law allegedly violating its terms. The court upheld the validity of the concordat, declaring that the circumstances of its conclusion under the Nazi regime did not invalidate it. However, the court also clarified that it lacked jurisdiction over matters of public international law and could not enforce the concordat uniformly, as education fell under the jurisdiction of individual states according to the German Basic Law.

Critics have argued that the concordat undermines the separation of church and state. While the Weimar Constitution – parts of which were incorporated into the current Basic Law (Grundgesetz) – prohibits a state religion, it allows for cooperation between church and state. Tensions persisted between provisions in the concordat, such as Article 18, and constitutional stipulations like Article 138, highlighting ongoing debates about the balance between religious freedom and state neutrality in postwar Germany.

Collaboration with Italian fascism: The Lateran Accords of 1929

The Vatican’s alignment with authoritarian regimes began earlier in Italy. The Lateran Accords, signed between the Holy See and Benito Mussolini’s fascist government on February 11, 1929, ended decades of tension stemming from the unification of Italy, during which the Papal States were annexed. These agreements established Vatican City as an independent state, recognized Catholicism as the state religion of Italy, and granted the Church significant privileges in education and public life.

Left: Cardinal Secretary of State Pietro Gasparri, representative of the Holy See, who signed the Lateran Accords in the name of the Vatican. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain) Right: Benito Mussolini, Prime Minister of Italy, who signed the Lateran Accords in the name of the Italian government. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

While the Lateran Accords resolved longstanding disputes, they also bound the Church to Mussolini’s regime. In return for institutional protections and financial compensation, the Church endorsed Mussolini’s government, legitimizing its rule. Catholic Action, a Church-affiliated organization, was permitted to operate under strict conditions, and Church leaders discouraged opposition to fascism among the faithful.

Vatican and Italian delegations prior to signing the Letran Treaty, February 20, 1929. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Mussolini exploited this alliance to bolster his authority, while the Church remained largely silent on the regime’s increasing repression, including its alignment with Nazi Germany and its anti-Semitic racial laws of 1938. The Vatican’s accommodation of Mussolini, while born of pragmatic concerns, compromised its moral authority and tacitly supported fascist policies.

Territory of Vatican City State, established by the Lateran Accords. Dark grey: territory of Vatican; light grey: territory of Vatican City. Security dispositive of Italy. Free access to public and to Italian police authorities may be revoked at any time for special ceremonial occasions; red: The small strip (3 m wide, 60 m long) alongside the northern colonnade is - according to the Lateran treaties - Italian territory and underlies Italian jurisdiction. This fact has been disputed by the mixed Italian-Vatican commission which was in place until 1932 to refine and detail the findings of the treaties. Since this commission had only a consultatory status Italy does not recognize any legal relevance of this dispute; blue zone: territory of Italy, but in possession of the Holy See. The area has extraterritorial status and Italian jurisdiction is not applied. The area contains the seat of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the bigger part of the en:Paul VI Audience Hall, the Campo Santo Teutonico and the German College; other: The light grey area next to the station has evidently been added in by mistake and is Italian territory.City Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

After 1946

After World War II, the Lateran Accords were incorporated into the 1948 Italian Constitution, ensuring the continuation of their framework. Despite Italy becoming a republic, the Catholic Church retained significant privileges, including recognition of Catholicism as the state religion.

In 1984, the concordat was revised to reflect a more secular state. Catholicism was no longer the official state religion, and exclusive financial support for the Church was replaced by the otto per mille tax system, which allowed taxpayers to support various recognized religious groups. The revisions also curtailed some Church privileges, such as state recognition of papal knighthoods, Church influence on political appointments of bishops, and automatic adoption of Italian laws by the Vatican. These changes marked a shift toward a more modern and independent relationship between the Church and the Italian state.

The Catholic Church and Franco’s Spain

The Catholic Church’s involvement in Francoist Spain was marked by an alliance that provided legitimacy to the regime and ensured the preservation of Church privileges, even as it became a controversial chapter in Spanish history. This collaboration began during the Spanish Civil War and extended well into Franco’s dictatorship, shaping the socio-political and religious landscape of the country.

The Church during the Spanish civil war

The Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939) had introduced progressive reforms aimed at reducing the Catholic Church’s influence in public life, including the separation of Church and State, the secularization of education, and restrictions on the Church’s property and activities. These measures, codified in the 1931 Constitution, alienated many Catholics and created tensions between the Church and the Republic.

As the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, the Catholic Church overwhelmingly aligned itself with Franco’s Nationalists, portraying the conflict as a “Crusade” against the godlessness, anarchy, and communism represented by the Republican side. The Church’s support was rooted in its institutional survival; many clergy and faithful had suffered persecution in Republican-held areas during the war, including widespread killings of priests, monks, and nuns, and the desecration of religious buildings during the so-called “Red Terror”. These events further solidified the Church’s alliance with Franco.

The Church’s role in Francoist Spain

After Franco’s victory in 1939, the Catholic Church became a central pillar of the regime. Franco presented his government as a defender of Catholic values, and the Church reciprocated by endorsing the regime and legitimizing its rule. The Church regained privileges it had lost during the Republic, including control over education, the restoration of confiscated properties, and a dominant role in Spanish cultural and social life.

Key aspects of the Church’s involvement included:

- Religious education: The Franco regime reinstated religious instruction in schools, making Catholicism a central part of the curriculum.

- Cultural influence: Public manifestations of Catholicism, such as religious processions and festivals, became highly visible, reflecting the intertwining of Church and State.

- Moral policing: The Church played a role in enforcing conservative social values, including the subordination of women and censorship of materials deemed immoral.

Controversy and criticism

While the Church enjoyed institutional benefits under Franco, its close association with the regime came at a significant cost to its moral authority. Critics argue that the Church became complicit in the repression and atrocities committed by Franco’s government, including the “White Terror”, which saw thousands executed or imprisoned for their political affiliations. Clergy often actively participated in or tacitly approved of these actions, and religious rhetoric was used to justify the regime’s policies.

The Church’s close alignment with Franco also alienated progressive and moderate Catholics, who criticized its role in supporting a regime that suppressed dissent and violated human rights. Figures like José Bergamín and Manuel Carrasco Formiguera voiced their opposition, though often at great personal risk; Carrasco Formiguera, for instance, was executed by Franco’s forces in 1938.

Post-Franco reflections

After Franco’s death in 1975 and Spain’s transition to democracy, the Church faced significant challenges in adapting to a secularizing society. In 1971, the Spanish bishops issued a partial acknowledgment of their role during the Civil War, recognizing their failure to act as ministers of reconciliation. However, more comprehensive apologies have been scarce, and the Church has largely emphasized its victimization during the Republican era while downplaying its collaboration with Franco.

The legacy of the Church’s role during Francoist Spain remains divisive. While some view it as a necessary alliance for survival during turbulent times, others see it as a betrayal of the Church’s spiritual mission in favor of political expediency. The Church’s inability to fully address its historical complicity continues to shape its relationship with Spanish society.

Ethical Implications

The Catholic Church’s agreements with authoritarian regimes in Germany, Italy, and Spain reveal complex ethical dilemmas. These alliances, while ensuring institutional survival and preserving influence, exposed the Church to significant moral compromises. The cost of these accommodations has been a lasting stain on the Church’s credibility, both as a moral authority and a defender of human dignity.

Silence on atrocities

The Church’s collaborations often required silence or tacit approval of the regimes’ oppressive actions. In Nazi Germany, the Reichskonkordat shielded the Church’s autonomy, but it came at the expense of addressing the systematic persecution of Jews, political dissidents, and other marginalized groups. Even as the Holocaust unfolded, the Vatican refrained from explicit public condemnations, prioritizing diplomatic neutrality over a prophetic moral stance.

Similarly, in Mussolini’s Italy, the Lateran Accords granted the Church financial and legal privileges but muted its criticism of fascist aggression and domestic repression. The Church largely ignored Mussolini’s expansionist wars and his suppression of political freedoms, focusing instead on maintaining its influence in Italian society.

In Spain, the Church not only aligned itself with Franco’s regime but also actively endorsed the Nationalist cause during the Spanish Civil War, framing it as a “Crusade” against atheism and communism. This alignment often justified or overlooked the “White Terror”, where thousands of perceived political enemies were executed or imprisoned by Franco’s forces. The Church’s rhetoric provided spiritual legitimacy to a regime that suppressed dissent and human rights.

Prioritizing institutional preservation

The Church’s actions during this period reveal an overriding concern for preserving its institutional power. The rise of communism in Europe, with its explicitly anti-religious agenda, further fueled the Church’s alignment with authoritarian regimes. These regimes, in turn, exploited the Church’s fears to secure legitimacy and societal control, often using religion to reinforce their own ideologies.

The Church’s strategy of accommodation reflected a belief that collaboration with authoritarian regimes was the lesser of two evils compared to atheistic communism. This pragmatic calculus, however, often blinded the Church to the human suffering wrought by its allies.

Post-war reckoning

After World War II, the Vatican faced growing criticism for its role in enabling and legitimizing authoritarian regimes. Pope Pius XII’s perceived silence during the Holocaust has remained one of the most contentious aspects of this legacy. While some defenders argue that the Pope acted discreetly to protect Jewish lives, his failure to take a public moral stand against Nazi atrocities has been widely condemned.

In post-war Spain, the Church’s close alliance with Franco delayed efforts to democratize and foster national reconciliation. By embedding itself in Francoist ideology, the Church became complicit in the regime’s oppressive policies, creating a deep rift with segments of Spanish society that continues to resonate.

Long-term consequences

The Church’s collaborations with totalitarian regimes in the 1930s and 1940s left a legacy of mistrust and moral ambiguity. While these alliances may have protected the Church’s institutional interests in the short term, they eroded its credibility as a defender of justice and human dignity. This period underscores the ethical risks of prioritizing institutional survival over prophetic witness, raising important questions about the role of religious institutions in political power struggles.

In hindsight, the Church’s failure to act decisively in defense of universal human rights during these dark chapters has cast a shadow over its moral authority, challenging its role as a voice for the oppressed and a defender of the faith.

Conclusion

The Catholic Church’s alliances with totalitarian regimes in the 20th century exemplify the dangers of compromising moral principles for institutional gain. The Reichskonkordat, the Lateran Accords, and the Church’s support for Franco reveal a consistent prioritization of self-preservation over prophetic witness.

While the Church has since sought to confront and atone for this history, these episodes serve as a stark reminder of the perils of aligning with oppressive powers. They challenge religious institutions to embody the principles of justice, human dignity, and moral courage, even in the face of existential threats. By reflecting on this history, the Church – and society at large – can draw lessons on the importance of resisting authoritarianism and upholding the values of freedom and human rights.

Update (Nov 16, 2024): Based on a new documentary by ARTEꜛ, I wrote a follow-up article on Reassessing Pius XII: New insights into the Catholic Church’s role during the Holocaust and the Ratlines.

References and further reading

- Wikipedia article on the Catholic Church and Nazi Germanyꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Nazi Persecution of the Catholic Church in Germanyꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Clerical fascismꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Lateran Treatyꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Catholicism in the Second Spanish Republicꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Francoist Spainꜛ

- Guenter Lewy, *Catholic Church and Nazi Germany *, 1964, Littlehampton Book Services Ltd, ISBN: 978-0297169215

- John F. Pollard, Vatican and Italian Fascism: A Study in Conflict, 2008, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521023665

- Peter Bartley, Catholics Confronting Hitler: The Catholic Church and the Nazis, 2016, IGNATIUS PR, ISBN: 978-1621640585

- Paul Preston, The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain, 2013, HarperPress, ISBN: 978-0006386957

- Stanley G. Payne, Franco and Hitler: Spain, Germany, and World War II, 2009, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300151220

- Karlheinz Deschner, Mit Gott und den Faschisten. Der Vatikan im Bunde mit Mussolini, Franco, Hitler und Pavelić, 2012, Günther, Stuttgart, 1965, Neuauflage: Ahriman, Freiburg im Breisgau 2012, ISBN 978-3-89484-610-7

- Karlheinz Deschner, Ein Jahrhundert Heilsgeschichte. Die Politik der Päpste im Zeitalter der Weltkriege, 2 Bände, Kiepenheuer und Witsch, Köln 1982/83; erw. Neuaufl. in 1 Band u.d.T. Die Politik der Päpste im 20. Jahrhundert, Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1991, ISBN 3-498-01282-7

- David I. Kertzer, The Pope at War: The Secret History of Pius XII, Mussolini, and Hitler, 2023, Random House, ISBN: 978-0812989960

- John Cornwell, Hitler’s Pope: The Secret History of Pius XII, 2000, Penguin, ISBN: 978-0140266818

- Michael Phayer, The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965, 2001, Indiana University Press, ISBN: 978-0253214713

- Susan Zuccotti, Under His Very Windows: The Vatican and the Holocaust in Italy, 2002, Yale University Press, ISBN: 978-0300093100

- Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, A Moral Reckoning: The Role of the Catholic Church in the Holocaust and Its Unfulfilled Duty of Repair, 2002, Alfred a Knopf Inc, ISBN: 978-0375414343

- Robert P. Ericksen, Complicity in the Holocaust: Churches and Universities in Nazi Germany, 2012, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-1139059602

- Richard Steigmann-Gall, The Holy Reich: Nazi Conceptions of Christianity, 1919–1945, 2009, Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 978-0521603522

comments