The Ratlines: Post-war escape networks for Nazis and fascists – with the complicity of the Catholic Church

The Ratlines were clandestine escape routes established after World War II to facilitate the flight of high-ranking Nazi officials, collaborators, and other war criminals from Europe. These networks allowed some of history’s most notorious figures, responsible for orchestrating the Holocaust and other atrocities, to evade justice. Operating in the shadowy aftermath of the war, the Ratlines exposed a complex interplay of geopolitical interests, ideological sympathies, and institutional complicity. In this post, we briefly explore the origins, key figures, and ethical implications of the Ratlines, focusing on the controversial role of the Catholic Church in enabling these escapes.

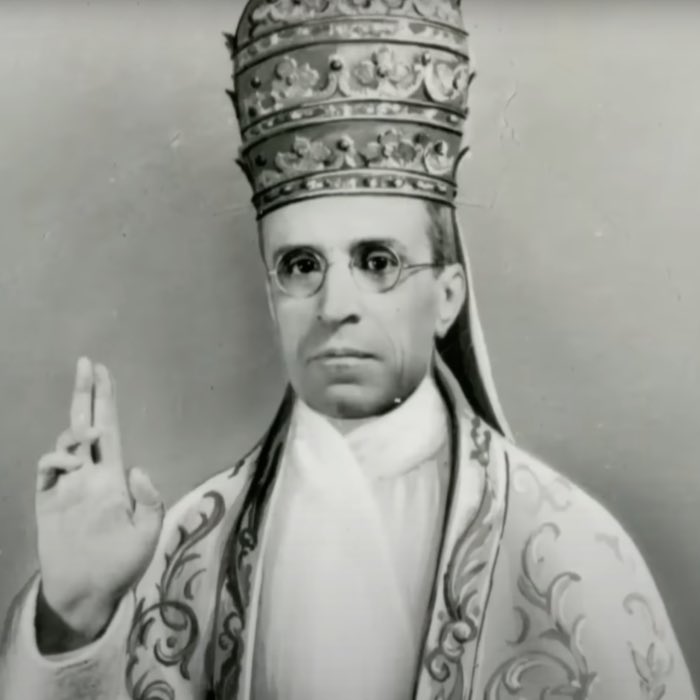

Pope Pius XII in 1951. What did the Vatican, and specifically Pope Pius XII, know about the Ratlines? This and other questions remain subjects of historical debate. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Origins of the Ratlines

The Ratlines emerged in a Europe devastated by war, where chaos and political upheaval created opportunities for covert operations. Allied forces had begun prosecuting Nazi war criminals at the Nuremberg Trials, but many sought to escape retribution. The immediate post-war years also saw the onset of the Cold War, which shifted Western priorities from denazification to countering Soviet influence.

Several factors contributed to the establishment of the Ratlines:

- Fear of communism: The West’s growing concern over Soviet expansion created an environment where former Nazis were viewed as potential allies in the fight against communism.

- Sympathy for fascist ideologies: Ideological alignment with fascism among certain European factions and sympathizers abroad facilitated assistance to escapees.

- Institutional complicity: The Catholic Church, humanitarian organizations, and even intelligence agencies played roles — sometimes unwittingly, often deliberately — in these networks.

- Post-war chaos: The disarray in occupied Europe made it easier for fugitives to forge new identities and exploit unregulated borders.

Key Ratline routes

The Ratlines operated primarily through Europe, funneling escapees to safe havens in South America, the Middle East, and even neutral European nations. The two main routes were:

Vatican route

Italy, and particularly Rome, served as the central hub for Ratline activity. High-ranking clergy, including Bishop Alois Hudal, were instrumental in providing escapees with forged documents and travel papers. These documents, often issued through the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), enabled fugitives to obtain visas and passage to countries like Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay.

Vatican City’s extraterritorial status provided a secure base for operations. Although the extent of the Holy See’s official involvement remains debated, numerous clergy members used Church resources to assist Nazi war criminals.

Spanish connection

Spain, under the fascist regime of Francisco Franco, became a key waypoint for escaping Nazis. Franco’s government, ideologically aligned with fascism, provided logistical support and temporary refuge. From Spain, escapees often secured maritime passage to South America.

South America: The final destination

South America, particularly Argentina, became the primary sanctuary for Nazi fugitives. Argentine President Juan Perón welcomed them, seeing an opportunity to strengthen his country’s technological and military capabilities. Other nations, such as Brazil, Paraguay, and Chile, also became havens.

Notable figures and cases

Among others, the Ratlines facilitated the escape of several infamous war criminals, allowing them to evade justice and live out their lives in exile. Here are a few notable cases.

High-ranking fascists and Nazis who escaped from Europe via the ratlines after World War II: Klaus Barbie (Gestapo chief), Josef Mengele (the “Angel of Death”), and Adolf Eichmann (architect of the holocaust). Sources: Wikimedia Commons 1ꜛ, 2ꜛ, and 3ꜛ (licenses: public domain)

Adolf Eichmann – Eichmann, a key architect of the Holocaust, escaped to Argentina in 1950 using a Ratline facilitated by Catholic clergy. Living under the alias Ricardo Klement, Eichmann worked in Buenos Aires until his capture by Israeli Mossad agents in 1960. He was tried and executed in Israel in 1962.

Josef Mengele – Known as the “Angel of Death” for his inhumane experiments at Auschwitz, Mengele fled to South America. Despite international efforts to apprehend him, Mengele evaded capture and died in Brazil in 1979.

Klaus Barbie – The “Butcher of Lyon”, responsible for torture and executions in Nazi-occupied France, escaped to Bolivia via the Ratlines. Barbie became a military advisor in Bolivia and was later extradited to France in 1983, where he was convicted of crimes against humanity.

The Role of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church’s involvement in the Ratlines represents one of the most contentious and morally ambiguous aspects of post-war history. While some Church officials framed their actions as humanitarian efforts to aid displaced individuals, others appeared motivated by ideological alignment with anti-communist goals or, in some cases, by a sense of loyalty to fascist collaborators. These activities were facilitated by a network of clerics and Church institutions operating with varying degrees of support from the Vatican.

Bishop Alois Hudal: Architect of escape

Alois Hudal, an Austrian bishop and rector of the Pontifical Teutonic College in Rome, played a pivotal role in orchestrating the Ratlines. A staunch anti-communist, Hudal used his ecclesiastical influence to assist fleeing Nazis, providing them with forged travel documents, financial aid, and access to safe houses. Hudal rationalized his actions in his memoirs, writing that his aim was to save individuals he considered victims of political retribution, particularly those persecuted by what he perceived as the growing Soviet menace.

Hudal’s operations extended beyond isolated acts of assistance. He was empowered by Pope Pius XII and Giovanni Montini (later Pope Paul VI) with broad authority to provide aid to displaced persons, ostensibly to address the humanitarian crisis following the war. However, Hudal exploited these powers to create a systematic escape network for high-ranking Nazis and fascists, including war criminals. Studies by historians such as Uki Goñi have revealed how the Vatican’s Secretariat of State, under the guise of diplomatic efforts, interceded on behalf of Croatian war criminals in Allied custody, seeking to prevent their extradition to Yugoslavia. This tacit support from the highest levels of the Church enabled Hudal to act with relative impunity.

The Vatican’s diplomatic maneuvering

The Vatican’s role in the Ratlines reflects a complex and often contradictory position. Officially, the Holy See condemned Nazi atrocities during the war. Yet in the post-war period, the Vatican prioritized the containment of communism over the pursuit of justice for war crimes. The Vatican’s Secretariat of State engaged in direct diplomatic efforts to protect collaborators of the fascist Ustaša regime in Croatia. British diplomatic correspondence reveals frustration with the Vatican’s harboring of such individuals in extraterritorial properties. Despite protests, the Church continued to offer sanctuary to fugitive fascists.

One prominent figure in these operations was Krunoslav Draganović, a Croatian Franciscan based at the Croatian National Church in Rome. Draganović used his position to facilitate the escape of numerous Ustaša officials, including military leaders and former ministers. Reports from American intelligence operatives noted that the premises of the Croatian National Church were a hub for fugitive fascists and that Vatican diplomatic vehicles were used to transport these individuals. The presence of high-ranking clergy, such as Giovanni Montini, at these locations raises questions about the level of Vatican awareness and complicity in these operations.

Allegations of Papal approval

The role of Pope Pius XII in the Ratlines, has been a subject of extensive debate among historians. While direct evidence of his explicit authorization remains elusive, several factors suggest at least tacit approval or awareness of these activities within the Vatican hierarchy.

Historical records indicate that the Vatican’s Secretariat of State, under Pope Pius XII, made diplomatic efforts to prevent the extradition of certain individuals associated with fascist regimes. For instance, in July 1943, German Ambassador Ernst von Weizsäcker reported to Berlin that the Vatican had intervened on behalf of Mussolini’s relatives and other fascists, seeking to protect them from retribution. Such actions demonstrate the Church’s willingness to engage politically to safeguard individuals linked to authoritarian regimes, even at the potential cost of its moral standing.

Key figures within the Church, such as Bishop Alois Hudal and Croatian priest Krunoslav Draganović, were instrumental in facilitating the escape of Nazi and fascist fugitives. Hudal, an Austrian bishop and rector of the Pontifical Teutonic College in Rome, openly assisted war criminals by providing them with forged documents and shelter. Draganović, operating from the Croatian National Church in Rome, organized escape routes for members of the Ustaša regime. The activities of these clerics, conducted within Vatican-affiliated institutions, suggest a level of institutional support or, at the very least, a lack of intervention from higher authorities.

Photographs from the era depict Giovanni Montini, who later became Pope Paul VI, visiting the Croatian National Church during a period when it was known to harbor fascist fugitives. While these images do not provide conclusive proof of direct involvement, they raise questions about the extent of awareness and oversight exercised by the Vatican’s leadership regarding the activities conducted within its premises.

Authors Mark Aarons and John Loftus have cited testimonies from clergy and intelligence reports suggesting that Pope Pius XII may have directly authorized aspects of the Ratline network. These accounts, while not definitive, contribute to the narrative that the Vatican, under Pius XII, played a more active role in these operations than previously acknowledged.

Conclusion: While definitive evidence of Pope Pius XII’s explicit approval of the Ratlines is lacking, the cumulative weight of diplomatic interventions, the involvement of high-ranking clergy, photographic documentation, and intelligence reports points to at least a tacit endorsement or a deliberate choice to remain uninformed.

Humanitarian concerns or ideological alignment?

While some Church officials justified their actions as humanitarian aid to displaced persons, the selective nature of this assistance raises significant ethical questions. The emphasis on aiding individuals aligned with Nazi or fascist ideologies, coupled with a disregard for their victims, suggests that these efforts were motivated less by humanitarianism and more by a desire to counter the perceived threat of communism. This ideological alignment overshadowed the Church’s moral responsibility to condemn and distance itself from individuals responsible for some of the 20th century’s most heinous crimes.

Legacy of the Church’s involvement

The Catholic Church’s involvement in the Ratlines has had a lasting impact on its moral and historical legacy. The actions of figures like Hudal and Draganović, coupled with the Vatican’s diplomatic interventions, reflect an institution willing to compromise its ethical principles for political expediency. While the Vatican has never fully acknowledged its role, the evidence points to a deliberate strategy that prioritized ideological objectives over justice and accountability.

This complicity, whether tacit or explicit, undermines the Church’s claims of neutrality during one of history’s darkest periods and continues to be a source of controversy and debate among historians and the faithful alike.

Cold war politics and allied complicity

The geopolitical dynamics of the Cold War played a significant role in the exploitation and perpetuation of Ratline networks. Western powers, particularly the United States and the United Kingdom, increasingly prioritized anti-communist objectives over the pursuit of justice for Nazi war crimes. As the Soviet Union emerged as the primary adversary in the post-war world, former Nazis and fascist collaborators became valuable assets in the West’s intelligence and scientific campaigns against the Eastern Bloc.

Recruitment of Nazi intelligence officers

One of the most notable examples of Allied complicity was the recruitment of Reinhard Gehlen, a high-ranking Nazi intelligence officer who had led the Wehrmacht’s military intelligence operations on the Eastern Front. Gehlen surrendered to U.S. forces in 1945 and offered his expertise on Soviet intelligence in exchange for protection and resources. His network, known as the “Gehlen Organization,” became a cornerstone of early Western intelligence efforts against the Soviet Union. Operating with substantial CIA funding, the organization employed numerous former Nazis, many of whom had been implicated in war crimes.

Gehlen’s integration into Western intelligence exemplifies the pragmatic approach of the Allies, who viewed the knowledge and experience of former Nazis as critical tools in the emerging Cold War. This strategy not only allowed war criminals to escape accountability but also lent a degree of legitimacy to Ratline operations, as fugitive Nazis could anticipate potential recruitment rather than prosecution.

Allied knowledge and utilization of Ratlines

Declassified documents and historical research reveal that Allied intelligence agencies were aware of the Ratlines and occasionally utilized them to their advantage. For example, American intelligence operatives collaborated with figures like Krunoslav Draganović, the Croatian cleric deeply involved in aiding Ustaša war criminals. Draganović’s network, initially established to assist Croatian refugees, became a pipeline for smuggling fascist collaborators to South America. While ostensibly independent, the network’s operations aligned with Western interests in shielding individuals who could provide strategic value against the Soviet Union.

The British MI6 similarly exploited Ratline networks, often turning a blind eye to the war crimes of those they sought to employ. Reports indicate that British agents facilitated the relocation of individuals who had worked with Nazi intelligence during the war, particularly those with connections to Eastern European anti-communist resistance movements.

Operation Paperclip and strategic recruitment

A parallel but distinct initiative, Operation Paperclip, further highlights the pragmatic decisions made by Western powers in the post-war era. Spearheaded by the United States, this program recruited German scientists and engineers, including those with direct ties to the Nazi regime, to advance American military and technological capabilities. While not directly connected to the Ratlines, Operation Paperclip demonstrated a similar willingness to prioritize Cold War objectives over moral considerations.

Key figures in the program included Wernher von Braun, a pioneering rocket scientist who had been a member of the Nazi Party and an SS officer. Despite his involvement in the V-2 rocket program, which relied on forced labor from concentration camp inmates, von Braun and others were granted U.S. citizenship and prominent roles in American scientific endeavors, including NASA’s space program.

Consequences of allied complicity

The exploitation of Ratline networks and the integration of former Nazis into Western institutions had far-reaching consequences. It undermined international efforts to achieve justice for war crimes and created a precedent for prioritizing strategic interests over accountability. Moreover, it fueled Soviet propaganda, which portrayed the West as hypocritical in its condemnation of Nazi atrocities while simultaneously collaborating with former Nazis.

The decision to shield and employ war criminals also contributed to the persistence of fascist ideologies in post-war societies. By enabling these individuals to escape prosecution and, in some cases, achieve positions of influence, the Allies inadvertently allowed elements of Nazi ideology to resurface in various forms, including in South American regimes that harbored fugitives.

Ethical and political implications

The existence and operation of the Ratlines present a deeply troubling intersection of ethics, justice, and political pragmatism. These escape networks highlight the difficult compromises made by institutions and nations in the face of competing moral and strategic priorities. Their legacy continues to provoke debates over the nature of justice, institutional accountability, and the ethical costs of geopolitical decision-making.

Justice deferred and denied

The Ratlines enabled thousands of Nazi and fascist war criminals, including high-ranking officials directly responsible for atrocities during the Holocaust and World War II, to evade prosecution. These individuals, many of whom orchestrated genocide, lived out their lives in relative comfort in South America, the Middle East, and elsewhere. The escape of such figures not only delayed justice but denied it entirely to the victims and survivors of Nazi brutality. The inability to hold these war criminals accountable cast a shadow over the post-war period, undermining efforts to provide closure and recognition for those who suffered.

The Nuremberg Trials and subsequent war crimes tribunals were hailed as a new standard for international justice, yet the Ratlines starkly contrasted this principle. By allowing perpetrators to escape legal consequences, these networks symbolized a failure to uphold the very ideals that the trials sought to enshrine.

Institutional complicity and moral failure

The role of the Catholic Church, humanitarian organizations, and even Allied intelligence agencies in facilitatingor tacitly endorsing the Ratlines raises serious questions about institutional complicity.

- The Catholic Church: While some clergy justified their actions on humanitarian grounds — claiming to help displaced individuals or protect those fleeing Soviet persecution — others, such as Bishop Alois Hudal, openly aligned with Nazi and fascist ideologies. Hudal’s use of Church resources, including Vatican facilities, to aid war criminals exemplifies the tension between moral responsibility and institutional survival. The Church’s broader silence on Ratline activities suggests a troubling prioritization of anti-communist objectives over accountability for war crimes.

- Humanitarian organizations: Groups such as the International Red Cross, which issued travel documents that facilitated escape, often operated with limited verification mechanisms. Although motivated by the chaotic post-war refugee crisis, their actions inadvertently abetted the evasion of justice for some of history’s most egregious criminals.

- Allied governments: The complicity of Western intelligence agencies, such as the CIA and MI6, in recruiting former Nazis for Cold War purposes reflects a pragmatic but ethically dubious approach. These agencies were not only aware of Ratline operations but actively exploited them to secure assets in the fight against communism, further undermining efforts to deliver justice.

Cold war pragmatism and its ethical costs

The geopolitical dynamics of the Cold War placed anti-communist priorities above the pursuit of justice. Former Nazis were viewed as valuable assets in intelligence and military operations, particularly in Eastern Europe. The recruitment of figures like Reinhard Gehlen, who integrated former Nazi operatives into Western intelligence networks, exemplifies the extent to which ideological battles overshadowed ethical considerations.

While the West’s realpolitik approach yielded short-term strategic advantages, it came at a significant moral cost. It undermined the post-war commitment to accountability, tarnished the moral authority of Western powers, and provided ammunition for Soviet propaganda, which highlighted the West’s willingness to collaborate with individuals implicated in Nazi atrocities.

Legacy and lessons

The Ratlines left a profound and troubling legacy. The complicity of religious, humanitarian, and governmental institutions in aiding war criminals damaged their moral standing. The Catholic Church, in particular, has faced ongoing criticism for its role, with calls for greater transparency and accountability.

For Holocaust survivors and victims of Nazi crimes, the escape of key perpetrators through Ratlines deepened the sense of injustice and betrayal. Efforts to prosecute war criminals decades later have been hindered by the passage of time and the secrecy surrounding Ratline activities.

The failure to prosecute many war criminals weakened the foundation of international law established by the Nuremberg Trials. It sent a message that political expediency could override the principles of accountability and justice.

A call for accountability

The Ratlines underscore the enduring tension between morality and pragmatism in international politics. While the Cold War context explains, though does not justify, the compromises made, the actions of the institutions and nations involved serve as a cautionary tale. Upholding justice and accountability, even in the face of competing priorities, remains essential to preserving the integrity of global institutions and honoring the memory of those who suffered under totalitarian regimes. The lessons of the Ratlines continue to resonate in contemporary debates over justice, reconciliation, and institutional responsibility.

Update (Nov 16, 2024): Based on a new documentary by ARTEꜛ, I wrote a follow-up article on Reassessing Pius XII: New insights into the Catholic Church’s role during the Holocaust and the Ratlines.

References and further reading

- Wikipedia article on the Ratlinesꜛ

- “What did the Vatican know about the Nazi escape routes?” (dw article)ꜛ

- “Die „Rattenlinie” nach Argentinien” (DLF article)ꜛ

- Karlheinz Deschner, Ein Jahrhundert Heilsgeschichte. Die Politik der Päpste im Zeitalter der Weltkriege, 2 Bände, Kiepenheuer und Witsch, Köln 1982/83; erw. Neuaufl. in 1 Band u.d.T. Die Politik der Päpste im 20. Jahrhundert, Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1991, ISBN 3-498-01282-7

- Karlheinz Deschner, Mit Gott und den Faschisten. Der Vatikan im Bunde mit Mussolini, Franco, Hitler und Pavelić, 2012, Günther, Stuttgart, 1965, Neuauflage: Ahriman, Freiburg im Breisgau 2012, ISBN 978-3-89484-610-7

- Ann-Christin Graé, Die katholische Kirche und die so genannte Rattenlinie: Der Vatikan als Fluchthelfer für Naziverbrecher, 2011, GRIN Verlag, Norderstedt, ISBN: 978-3-640-79364-8

- Ernst Klee, Persilscheine und falsche Pässe. Wie die Kirchen den Nazis halfen, 1991, Fischer, Frankfurt, ISBN: 3-596-10956-6

- Rena und Thomas Giefer, Die Rattenlinie. Fluchtwege der Nazis, 1992, Beltz, Weinheim, ISBN: 3-89547-855-5

- Johannes Sachslehner, Hitlers Mann im Vatikan: Bischof Alois Hudal. Ein dunkles Kapitel in der Geschichte der Kirche, 2019, Molden, Wien-Graz, ISBN: 978-3-222-15040-1

- Philippe Sands, Die Rattenlinie. Ein Nazi auf der Flucht. Lügen, Liebe und die Suche nach der Wahrheit, 2020, S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, ISBN: 978-3-10-397443-0

- Gerald Steinacher, Nazis auf der Flucht. Wie Kriegsverbrecher über Italien nach Übersee entkamen, 2008, StudienVerlag, Innsbruck-Wien-Bozen ISBN: 978-3-7065-4026-1

- Eckhard Schimpf, Heilig. Die Flucht des Braunschweiger Naziführers auf der Vatikan-Route nach Südamerika, 2005, Appelhans, Braunschweig, ISBN: 978-3-937664-31-6

- Daniel Stahl, Nazi-Jagd: Südamerikas Diktaturen und die Ahndung von NS-Verbrechen, 2013, Wallstein, Göttingen, ISBN: 978-3-8353-1112-1

comments