Paragraph 175

For over a century, Paragraph 175 of the German Criminal Code represented the legal persecution of homosexual men in Germany. Originally introduced in 1871, it was not merely a statute but a symbol of systemic discrimination that endured through various political regimes, including the devastating intensification under the Nazis. Its impact continued long after World War II, with postwar Germany carrying forward its oppressive legacy until its final repeal in 1994. This article examines the history of Paragraph 175, its chilling effects on LGBTQ+ lives, and the long road to justice for its victims.

“Down with §175” poster. Since 1973 the gay movement had openly been demanding the deletion of Paragraph 175. This 1973 poster uses the new left icon of a raised fist and calls on the reader to fight against discrimination in the family, in the workplace, and in individuals’ search for housing. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: BY-SA 4.0)

Origins of Paragraph 175

Paragraph 175 was adopted in 1871, shortly after the unification of Germany under Prussian leadership. It criminalized “unnatural fornication” between men and, initially, bestiality. Inspired by earlier legal codes such as Prussia’s 1794 Allgemeines Landrecht and the medieval Constitutio Criminalis Carolina, the provision reflected deeply rooted societal and religious prejudices against homosexuality. These prejudices were strongly influenced by the teachings of the Catholic Church, which viewed homosexuality as a grave sin.

The Catholic Church’s influence

The Catholic Church played a pivotal role in shaping societal and legal perceptions of homosexuality in medieval and early modern Europe. Drawing on biblical passages such as the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah (Genesis 19:1–29) and condemnations of “unnatural” acts in the writings of Saint Paul (Romans 1:26–27), the Church defined homosexuality as a violation of divine and natural law. Canon law explicitly prohibited sodomy, categorizing it alongside other “unnatural sins” as offenses against God.

Burning of the accused sodomites, Richard Puller von Hohenburg and Anton Mätzler, outside the walls of Zürich, 1482. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: BY-SA 4.0)

The Church’s teachings were not merely spiritual edicts; they influenced secular laws and judicial practices. In the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina of 1532, for example, sodomy was punishable by death, reflecting the Church’s position that such acts were both morally reprehensible and deserving of the severest penalties. This alignment of religious doctrine with civil law led to the persecution of individuals accused of sodomy, often through public executions by burning, as vividly illustrated in the 1482 case of Richard Puller von Hohenburg and Anton Mätzler in Zürich.

Homosexuality as a threat to social order

The Catholic Church’s condemnation of homosexuality extended beyond theological arguments. Homosexual acts were portrayed as threats to social order, family structures, and procreation — values central to the Church’s vision of a moral society. By stigmatizing and criminalizing homosexuality, Church leaders sought to maintain control over sexual behavior and enforce conformity to traditional gender roles.

This legacy persisted into the modern era, influencing the framing of Paragraph 175 in 1871. While the unification of Germany marked a shift toward centralized legal systems, Christian moral principles, deeply entrenched in German culture, continued to shape penal codes. The inclusion of homosexuality under the rubric of “unnatural fornication” was not only a reflection of contemporary societal norms but also a continuation of centuries of religiously motivated legal frameworks.

Progressive Developments Elsewhere

In contrast to Germany’s codification of religiously inspired morality, neighboring France had decriminalized homosexuality during the French Revolution. The secular principles of the Napoleonic Code, introduced in 1791, removed sodomy laws and treated private, consensual sexual acts as matters outside the state’s concern. This progressive stance highlighted a stark divergence between France’s embrace of Enlightenment ideals and Germany’s adherence to traditional, Christian-influenced legal codes.

Early challenges and the Weimar Republic’s promise

Resistance to Paragraph 175 emerged in the late 19th century with the formation of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (WhK) in 1897, led by the pioneering sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld. The committee campaigned for the decriminalization of homosexuality, arguing that it was an innate characteristic rather than a moral failing. Although petitions and advocacy efforts gathered thousands of signatures and some political support, they failed to repeal the law.

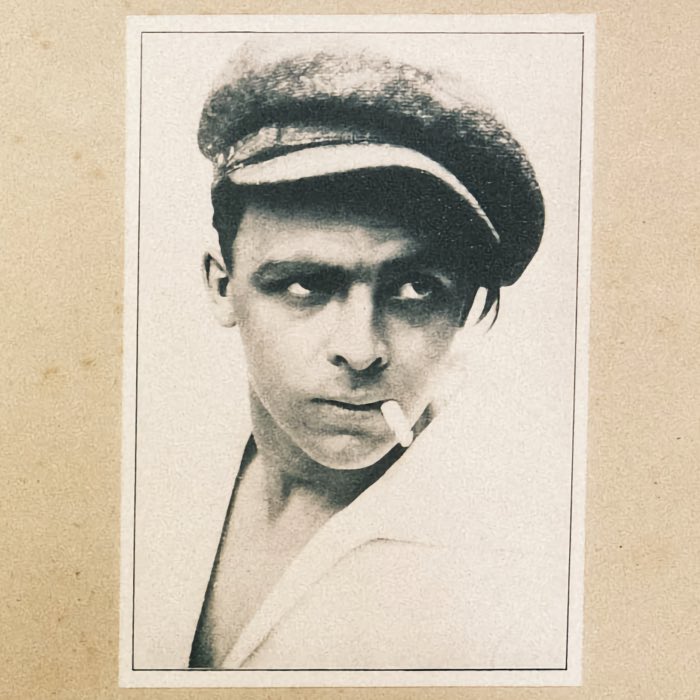

The left-wing publicist Kurt Hiller published a collection of essays against § 175 in 1922. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Weimar Republic (1918–1933) brought new hope to LGBTQ+ activists. Berlin flourished as a hub of queer culture, with bars, clubs, and publications that celebrated sexual diversity. In 1929, a Reichstag committee narrowly voted to repeal Paragraph 175, supported by Social Democrats, Communists, and progressive liberals. However, the onset of the Great Depression and the rise of the Nazi Party derailed this progress.

Intensification under the Nazis

The Nazi regime weaponized Paragraph 175 to target homosexual men as part of their broader agenda of enforcing racial and social conformity. In 1935, the law was broadened to criminalize any “lewd act” between men, even non-physical gestures. Convictions under Paragraph 175 soared from approximately 1,000 per year during the Weimar era to over 8,000 annually by the late 1930s.

The Gestapo used Paragraph 175 to justify arbitrary arrests, often sending those convicted to concentration camps, where they were forced to wear the pink triangle. Of the estimated 10,000 homosexual men sent to the camps, most perished under brutal conditions, subjected to forced labor, medical experiments, and systemic violence.

Continuity after World War II

The defeat of the Nazis in 1945 did not bring immediate relief for homosexuals persecuted under Paragraph 175. In a chilling continuation of Nazi policies, West Germany retained the 1935 version of the law. Men who had survived concentration camps were often re-arrested to complete their sentences. The Federal Constitutional Court upheld the validity of Paragraph 175 in 1957, ruling that it was not a product of Nazi ideology.

Graph of convictions under Paragraph 175. Spike occurs during Nazi era. After the fall of the Nazi regime, however, convictions continued. Note that the numbers of convictions during the early years of the Federal Republic of Germany (BRD) are lower than those during the Nazi era, but still magnitudes higher than in the Weimar Republic. The graph shows a significant spike in convictions in the early 1950s. A significant drop in convictions occurred after 1968 after a partial repeal of the law. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: BY-SA 2.5)

Between 1945 and 1969, approximately 100,000 men were charged under Paragraph 175 in West Germany, with around 50,000 convictions. The stigma attached to homosexuality remained deeply entrenched, causing countless men to live in fear and secrecy. Many committed suicide under the weight of criminal charges or social ostracism.

In East Germany, the Nazi-era amendments were repealed in 1950, reverting to the pre-1935 version. By the late 1950s, prosecution of consensual homosexual acts between adults had effectively ceased, and Paragraph 175 was removed entirely from East German law in 1988.

Reform and repeal in West germany

The social upheavals of the 1960s brought gradual liberalization to West Germany. In 1969, under the Social Democratic Party (SPD), Paragraph 175 was reformed, decriminalizing consensual homosexual acts between men over 21 years old. However, “qualified cases”, such as those involving men under 21 or exploitation of dependency, remained punishable. The age of consent for heterosexual relationships was significantly lower, reflecting ongoing discrimination.

Further reforms in 1973 lowered the age of consent for homosexual acts to 18, but full equality remained elusive. It was only after the reunification of Germany in 1990 that the Bundestag decided to reconcile the legal codes of East and West. On March 10, 1994, Paragraph 175 was repealed entirely, establishing a uniform age of consent for all sexual relationships.

Justice and remembrance

The long shadow of Paragraph 175 extended into the 21st century. In 2002, Germany annulled Nazi-era convictions of homosexuals, recognizing the injustice of their persecution. However, postwar convictions remained unaddressed until 2017, when the Bundestag passed a law pardoning men convicted under Paragraph 175 after 1945. Victims were awarded compensation: €3,000 per conviction and €1,500 for each year of imprisonment.

The pink triangle, once a symbol of shame, was reclaimed by the LGBTQ+ rights movement as a symbol of resistance and remembrance. Memorials and educational initiatives have since honored the lives lost and shattered by Paragraph 175.

Lessons from history

The history of Paragraph 175 reveals the devastating consequences of systemic discrimination enshrined in law. It underscores the importance of vigilance in protecting human rights and the fragility of progress in the face of authoritarianism and prejudice.

By remembering the struggles and resilience of those who suffered under Paragraph 175, we honor their legacy and reaffirm our commitment to a world where love and identity are celebrated rather than condemned.

comments