Magnus Hirschfeld and Germany’s pioneering role in LGBTQ+ rights

Long before the Stonewall Riots ignited the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement, Germany was a global pioneer in advancing understanding, acceptance, and advocacy for sexual minorities. At the heart of this movement was the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Institute for Sexual Science), founded by the visionary Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld in 1919. In this posts, we explore Germany’s early contributions to LGBTQ+ rights, the devastating impact of the Nazi regime on this progress, and the lasting consequences of the persecution faced by homosexuals during the Third Reich.

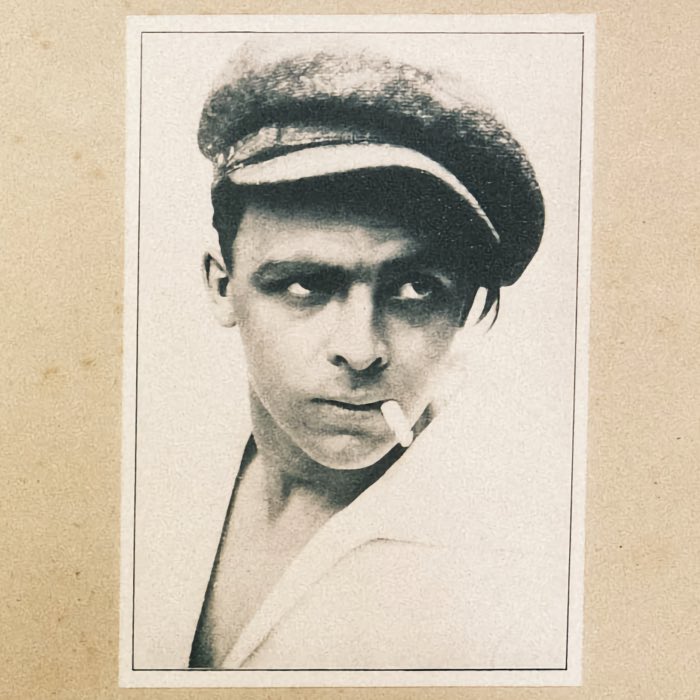

Magnus Hirschfeld, 1929, is the founder of the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Institute for Sexual Science) in Berlin. Hirschfeld was a pioneering advocate for LGBTQ+ rights and a leading figure in the early 20th-century movement for sexual liberation. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: BY-SA 4.0)

Magnus Hirschfeld and the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft

Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld (1868–1935), a Jewish physician and sexologist, was a trailblazing advocate for LGBTQ+ rights. His life’s work focused on dismantling misconceptions about sexuality and gender, challenging the stigma surrounding homosexuality, and advocating for the decriminalization of same-sex relationships. Hirschfeld believed that understanding human sexuality required a scientific approach, and his institute became the epicenter of research, education, and activism in this field.

The Institut für Sexualwissenschaft, founded in Berlin in 1919, was a groundbreaking institution that housed an extensive library, provided medical care and counseling, and hosted public lectures. The institute was also a safe haven for LGBTQ+ individuals, offering legal support and advocating for the repeal of Paragraph 175 of the German Penal Code, which criminalized male homosexuality.

Hirschfeld’s institute conducted pioneering research, documenting the diversity of human sexuality and gender expression. It introduced concepts that were far ahead of their time, including the idea that gender identity and sexual orientation exist on a spectrum. His advocacy for transgender individuals led to some of the world’s first gender-affirming surgeries being performed under the institute’s care.

Hirschfeld with the Chinese doctor Li Shiu Tong, who was his longtime companion and lover. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: BY-SA 4.0)

In the following, the main activities of the institute are described in more detail, highlighting its impact on LGBTQ+ rights and sexual health.

Public Education and Advocacy

One of the institute’s core missions was to educate both specialists and the general public about sexuality and gender. Its doors were open to visitors from around the world, including renowned figures like André Gide, Margaret Sanger, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Harry Benjamin. The institute hosted lectures, question-and-answer sessions, and public tours, addressing topics such as contraception, sexual orientation, and gender identity.

A highlight of the institute was its Museum of Sexual Subjects, which showcased ethnographic exhibits on diverse sexual norms across cultures, collections of phallic artifacts, and presentations on sexual diversity. These displays were both educational and thought-provoking, aiming to normalize and celebrate the wide spectrum of human sexuality. Visitors like Dora Russell described the museum as a space where “the results of researches into various sex problems and perversions could be seen in records and photographs.”

The institute also conducted international exchanges, including visits to and from Soviet officials interested in progressive approaches to sexual and reproductive health. Such cross-cultural dialogues underscored the institute’s reputation as a global leader in sexual science.

Sexual and reproductive health services

The institute provided vital medical and counseling services to people of all social classes. Through its Eugenics Department for Mother and Child and the Center of Sexual Counseling for Married Couples, it offered contraception access, marital counseling, and treatments for venereal diseases and impotence. It distributed hundreds of thousands of pamphlets on birth control, despite restrictive advertising laws, and prioritized serving the working class and poor.

Poster for Hirschfeld’s movie “Laws of Love: From the Portfolio of a Sexologist” (Gesetze der Liebe: Aus der Mappe eines Sexualforschers) 1927. Like its predecessor film from 1919, Anders als die Andern (“Different from the Others”) – believed to be the first film in the world which positively depicted gay men – it campaigned against Paragraph 175, the provision of the German Penal Code which prohibited sex between men. The film dealt with sexual intercourse in the animal kingdom, discussing gestation, birth, and the nurturing of newborns, before dealing with “sexual intermediates” in chapter four, a term used by Hirschfeld to refer to certain gender and sexual minorities: hermaphrodites (intersex people), transvestites (cross-dressing and transgender people) and homosexuals. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The institute’s innovative approach extended to sex counseling. Rather than stigmatizing or pathologizing individuals, it sought to empower them to navigate their sexual lives in a homophobic society. Hirschfeld and his colleagues promoted acceptance and self-awareness, developing practices that would influence modern sexual health counseling.

Transgender and intersex advocacy

The institute was a pioneering advocate for transgender and intersex individuals. Hirschfeld introduced the term transsexual in 1923 and supported some of the earliest gender-affirming surgeries in history, including a groundbreaking case in 1931. Services offered included hormone therapy, early facial feminization surgery, and sex reassignment surgeries. The institute also issued transvestite passes to protect transgender individuals from police harassment for cross-dressing.

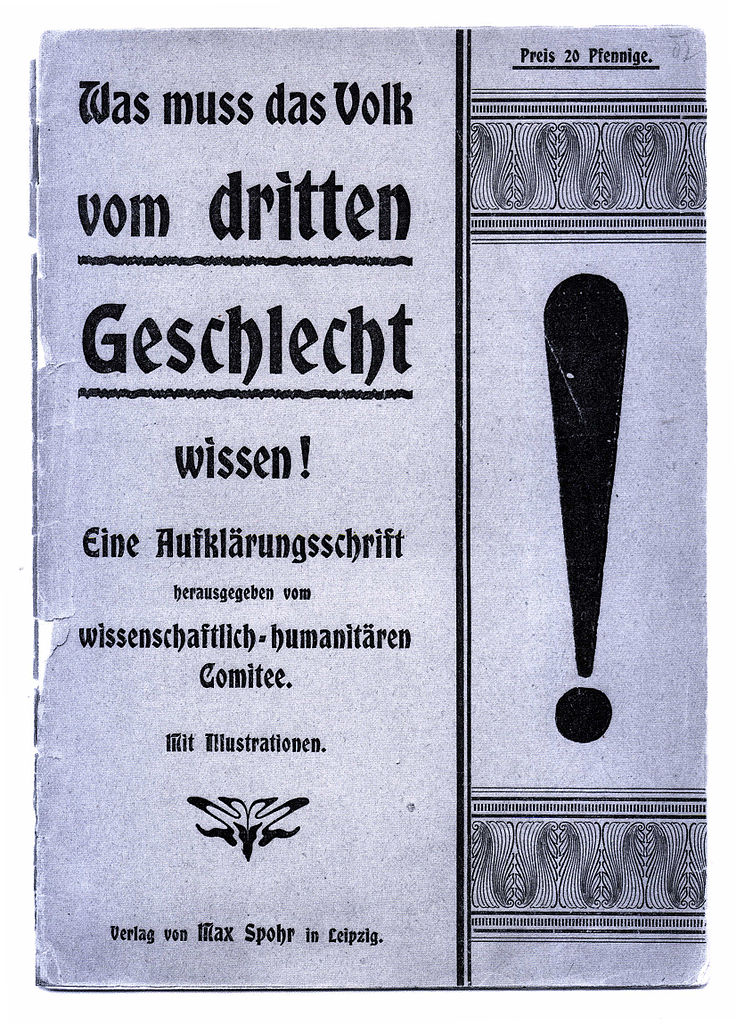

Educational pamphlet Was muss das Volk vom dritten Geschlecht Wissen! (“What must the people know about the third sex!”), published by Magnus Hirschfeld in 1901.

Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

Intersex advocacy was another cornerstone of Hirschfeld’s work. He believed intersex individuals should have the right to choose their gender upon reaching adulthood and provided medical services that aligned with this philosophy. Photographs and case studies at the institute were used to educate the public about the natural diversity of human biology.

Homosexuality: Research, support, and advocacy

Hirschfeld, himself a gay man, viewed homosexuality as a natural variation of human sexuality. The institute housed the first comprehensive archive on homosexuality and promoted adaptation therapy to help patients cope with societal stigma. It worked to build a sense of community for LGBTQ+ individuals, connecting them with supportive networks and venues while providing psychological and medical assistance.

Anders als die Andern (“Different from the Others”), movie poster from 1919. Magnus Hirschfeld co-wrote the script for this film, which was one of the first to portray homosexuality in a positive light. The film was a plea for tolerance and understanding, advocating for the repeal of Paragraph 175 of the German Penal Code, which criminalized homosexuality. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The institute’s efforts also included public advocacy, such as the screening of Different from the Others (1919), a groundbreaking film that called for tolerance toward homosexuals. The institute’s researchers sought to establish a biological basis for homosexuality, not as a “cure” but to counter arguments that it was unnatural or immoral.

This expanded section paints a vivid picture of the institute’s multifaceted work and its enduring significance in the history of LGBTQ+ rights. Would you like to include more details or specific anecdotes from the institute’s activities?

Germany’s LGBTQ+ movement: A beacon of hope

During the Weimar Republic (1918–1933), Germany became a center of LGBTQ+ culture and activism. Berlin, in particular, was renowned for its vibrant queer nightlife and progressive attitudes. Publications such as Der Eigene, the world’s first homosexual magazine, and organizations like the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, founded by Hirschfeld, provided platforms for discussion, advocacy, and community building.

Evidence of homosexual life and culture in Cologne before 1933. The magazine Der Eigene, published before the Nazi era, was the world’s first homosexual magazine and a hub for progressive thought on sexuality. Its existence reflects the early 20th century’s initial advances in homosexual rights, which were quickly reversed by the Nazis.

Evidence of homosexual life and culture in Cologne before 1933. The magazine Der Eigene, published before the Nazi era, was the world’s first homosexual magazine and a hub for progressive thought on sexuality. Its existence reflects the early 20th century’s initial advances in homosexual rights, which were quickly reversed by the Nazis.

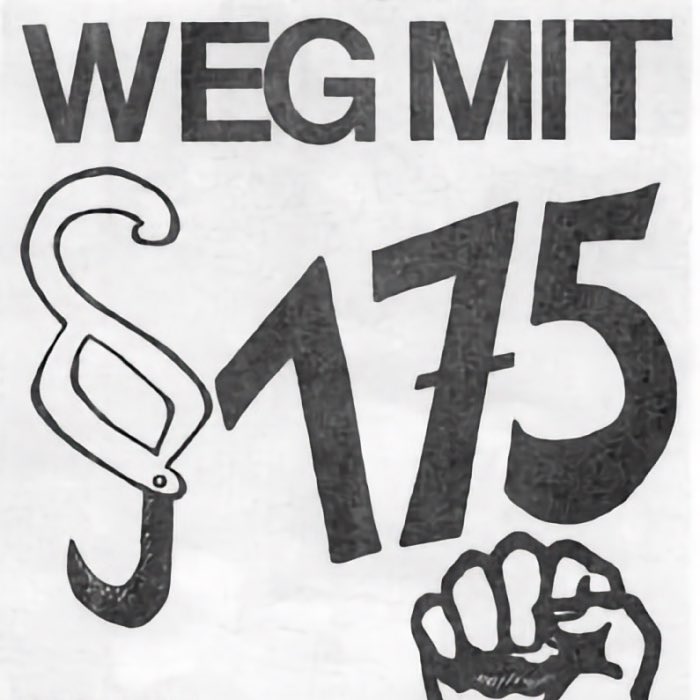

The LGBTQ+ movement in Germany during this era was remarkable for its ambition and inclusivity. Activists lobbied for the abolition of Paragraph 175, arguing that love and sexuality between consenting adults should not be a matter of criminal law. They also worked to educate the public about homosexuality, challenging the prejudices of the time with scientific evidence and personal testimonies.

The rise of the Nazis: An end to progress

The ascent of the Nazi Party in 1933 brought an abrupt and catastrophic end to Germany’s LGBTQ+ movement. The Nazis, with their emphasis on a narrowly defined “racial purity” and traditional gender roles, saw homosexuality as a threat to their vision of an idealized Aryan society.

Students of the German University of Physical Education in front of the institute before the looting on May 6, 1933. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

On May 6, 1933, the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft was raided by Nazi youth and its extensive archives were destroyed in one of the infamous book burnings. The event symbolized the regime’s rejection of diversity, science, and progressive thought. Hirschfeld, already in exile due to anti-Semitic and anti-LGBTQ+ threats, witnessed the destruction of his life’s work from afar.

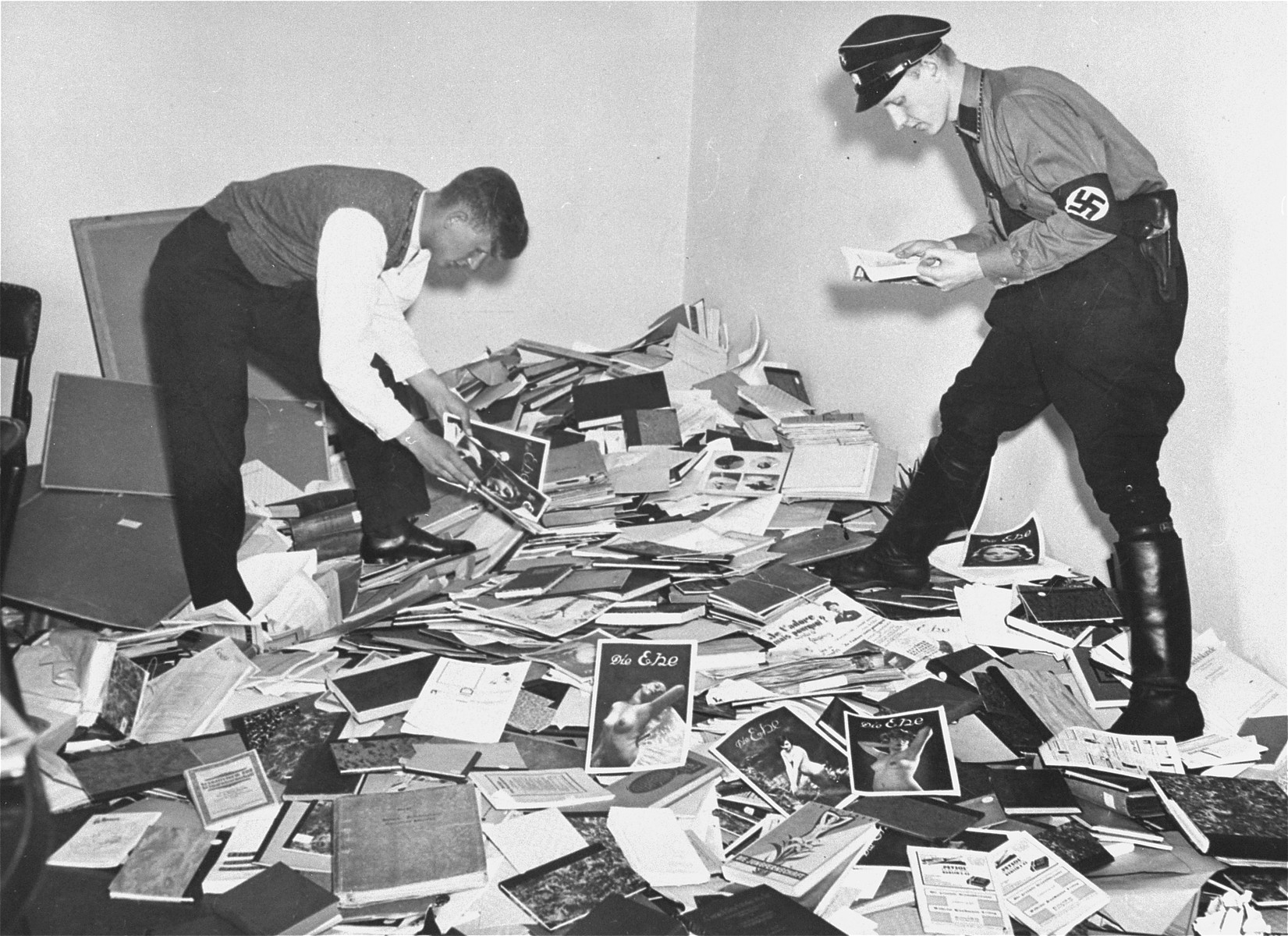

German students and Nazi SA members plunder the library of Magnus Hirschfeld, director of the institute, 1933. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain)

The Nazis intensified Paragraph 175 in 1935, broadening its scope to criminalize even non-physical expressions of homosexuality. Convictions under Paragraph 175 skyrocketed, with over 50,000 men sentenced during the Third Reich. Homosexual men were sent to prisons and concentration camps, where they were forced to wear the pink triangle – now a symbol of LGBTQ+ resistance and remembrance. In these camps, they faced brutal conditions, ostracization, medical experiments, and often death.

Lesbian women, while not directly targeted by Paragraph 175, were persecuted under the Nazis’ broader classification of “asocials.” Many were subjected to forced labor, sterilization, and incarceration in concentration camps.

The consequences of Nazi persecution

The destruction of the LGBTQ+ movement in Germany had profound and lasting effects. After the war, survivors of Nazi persecution faced continued discrimination. Paragraph 175 remained in force in West Germany until 1969, and many LGBTQ+ individuals were re-imprisoned or denied recognition as victims of the Nazi regime. Reparations were scarce, and the stigma associated with homosexuality persisted, silencing many survivors.

The memory of Hirschfeld’s institute and Germany’s pioneering role in LGBTQ+ rights was nearly erased. It was only in the late 20th century, thanks to the efforts of activists and historians, that this chapter of history was rediscovered and celebrated. The pink triangle, once a mark of shame, became a powerful symbol of LGBTQ+ resilience and a reminder of the dangers of intolerance.

Legacy and lessons

Germany’s early LGBTQ+ movement and the work of Magnus Hirschfeld remain a testament to the power of science, education, and advocacy in challenging prejudice and promoting human rights. The devastation wrought by the Nazi regime underscores the fragility of progress and the importance of safeguarding freedoms against the forces of hate and authoritarianism.

Today, Hirschfeld’s legacy endures in the global LGBTQ+ rights movement, inspiring efforts to create a more inclusive and equitable world. His institute’s destruction serves as a stark reminder of what can be lost when diversity and knowledge are attacked.

By remembering this history, we honor the courage of those who fought for LGBTQ+ rights in the face of unimaginable adversity and reaffirm our commitment to a future where love, identity, and freedom are celebrated, not punished.

References and further reading

- Wikipedia article on the Institut für Sexualwissenschaftꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Homosexuality durign the Nazi regimeꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Rosa Winkelꜛ

- Holocaust Encyclopedia on Magnus Hirschfeldꜛ

- Website of the Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft e.V.ꜛ

- Website of the Bundesstiftung Magnus Hirschfeldꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Gestez der Liebe movieꜛ

- Wikipedia article on Anders als die Andern movieꜛ

comments