Youth resistance groups in Cologne against the Nazi regime

“Resistance” under the Nazi regime often evokes images of organized military operations or clandestine political movements. However, throughout Germany, and especially in cities like Cologne, resistance also took root in less expected places: among the youth. Defying the rigid conformity demanded by the Nazis, many young people in Cologne organized into resistance groups, using whatever means they had to express their opposition to a regime that demanded obedience and submission.

These youth resistance groups, often informal and decentralized, expressed their defiance in ways ranging from subtle acts of nonconformity to bold public protests. In this post, I highlight some of the most prominent youth groups in Cologne that opposed the Nazis, as presented in the El-De Haus exhibition. Their stories offer insight into the courage and resilience of the young people who resisted the oppressive Nazi regime.

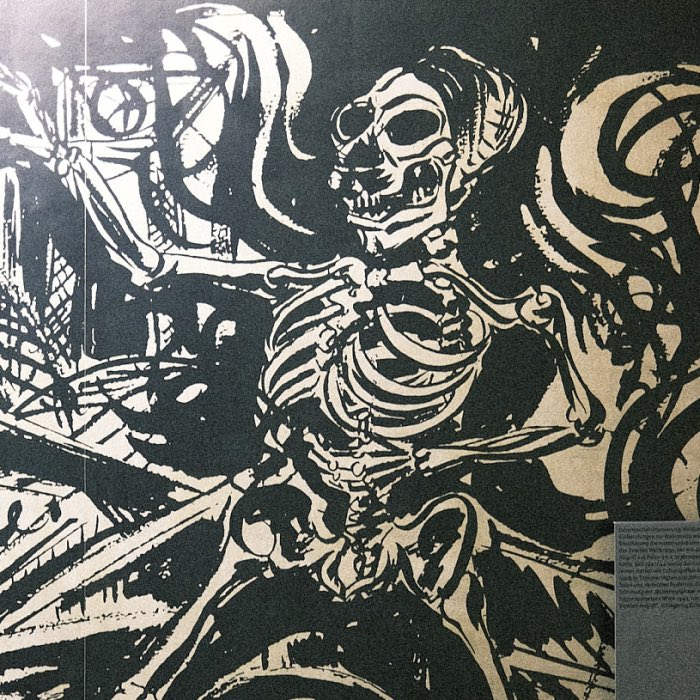

Protest action against voting for the Nazis, exemplifying the grassroots efforts led by Cologne’s youth in defiance of Nazi control.

Protest action against voting for the Nazis, exemplifying the grassroots efforts led by Cologne’s youth in defiance of Nazi control.

Introduction

Youth resistance to the Nazi regime in Cologne reflected a unique form of defiance. Unlike structured resistance movements, which were often politically organized and driven by adult leaders, youth resistance arose more spontaneously, frequently motivated by a desire for freedom and self-expression rather than specific political goals. Many young people resented the strict ideological education and militaristic discipline imposed by the Hitler Youth, the Nazi organization established to indoctrinate Germany’s youth. Instead, these young people formed their own groups, often inspired by values and ideals starkly opposed to Nazi principles.

For many, this resistance took the form of reclaiming cultural spaces, practicing forbidden hobbies, and connecting with like-minded peers in a society that increasingly valued conformity over individuality.

Edelweiss Pirates

One of the most notable youth resistance groups in Cologne was the Edelweiss Pirates (Edelweiss Piraten). The Edelweiss Pirates were informal groups of German youth in the late 1930s and early 1940s, known for their opposition to Nazi ideology and their refusal to conform to the strict, militarized expectations imposed on young people. Formed as a reaction against the Hitler Youth’s compulsory membership and control over social activities, the Edelweiss Pirates represented a grassroots rebellion rooted in nonconformity. These youth groups, active primarily between 1939 and 1945, continued their activities in some occupation zones until around 1947. The Gestapo initially coined the name Edelweiss Pirates as a derogatory term in 1939, referencing the Edelweiss flower, a popular symbol among youth groups like the Bündische Jugend, which had been banned in 1936.

As Nazi surveillance intensified, several factions of the Edelweiss Pirates, including the Cologne Edelweiss group led by Gertrud Koch, and the Ehrenfeld Group led by concentration camp escapee Hans Steinbrück, became particularly prominent for their resistance activities. The Ehrenfeld Group’s story, largely unknown until it was publicized by survivor Jean Jülich in the 1980s, highlights the courage of these youth in the face of brutal repression. Similarly, the Dortmund Edelweiss Pirates from Brüggemann Park gained recognition for their resistance efforts, later documented in a book by author Kurt Piehl.

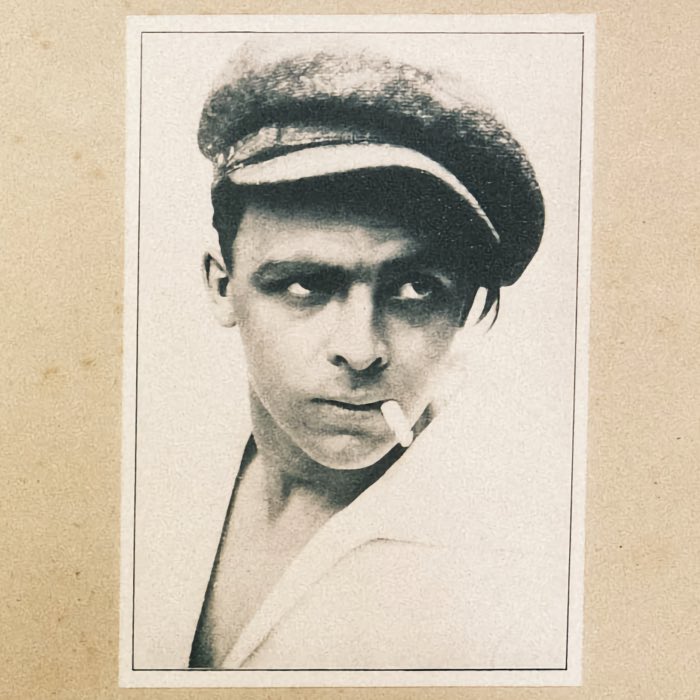

Edelweiss Pirates in Beethoven Park, 1943. Their gatherings, music, and nonconformist behavior represented a form of cultural resistance.

Edelweiss Pirates in Beethoven Park, 1943. Their gatherings, music, and nonconformist behavior represented a form of cultural resistance.

Origins

The roots of the Edelweiss Pirates lay in earlier German youth movements like the Wandervogel and Bündische Jugend, which emphasized independence, camaraderie, and a return to nature. During the Weimar Republic, these groups organized hikes, campfires, and outdoor excursions, fostering a sense of freedom and self-expression that contrasted with the Nazi emphasis on rigid conformity. Although these youth movements were banned in 1936, their spirit continued to influence the Edelweiss Pirates, who adopted their songs, outdoor activities, and even attire as acts of defiance.

In contrast to the Hitler Youth, whose members wore military-style uniforms, the Edelweiss Pirates developed their own distinct style, characterized by ski shirts, hiking boots, neckerchiefs, and short leather trousers. Some wore an Edelweiss emblem under their lapel, while others donned fantasy garb, death’s head rings, studded belts, or jackets typical of the former Bündische Jugend. These fashion choices, along with their love for folk songs and reimagined Hitler Youth songs that conveyed subversive, anti-Nazi messages, symbolized their refusal to conform.

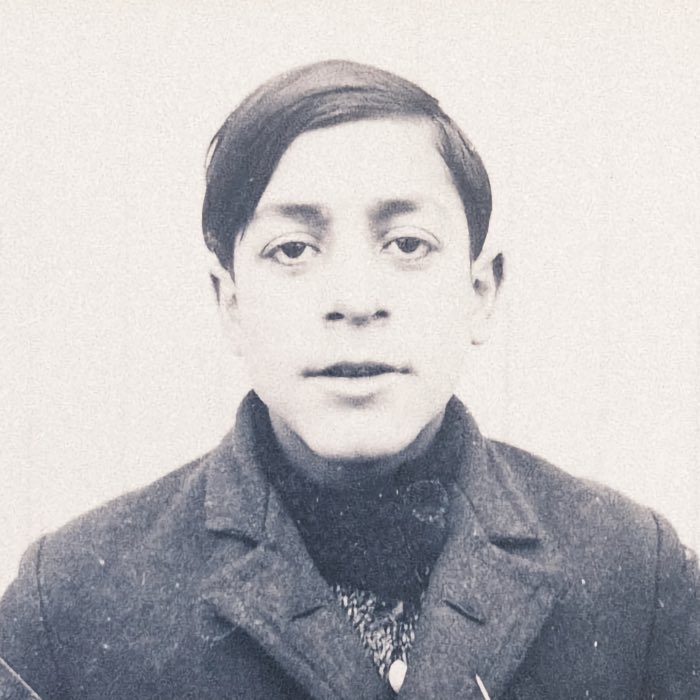

Cologne Edelweiss pirates on the Rhine, around 1940.

Cologne Edelweiss pirates on the Rhine, around 1940.

Resistance and escalation to active defiance

As the war intensified, so did the Nazi crackdown on Edelweiss Pirate activities. By 1942, Cologne became a hub for the Edelweiss groups, with over 3,000 names documented in Gestapo records. In other cities like Duisburg, Düsseldorf, Essen, and Wuppertal, police raids uncovered hundreds more suspected Pirates. For the Nazi regime, the Edelweiss Pirates’ growing visibility posed a threat, as these youths not only rejected Nazi values but actively mocked and resisted them.

The Pirates’ defiance ranged from graffiti and sharing banned songs to more direct actions, such as harboring escaped prisoners, aiding Jews, and conducting sabotage. The Ehrenfeld Group under Hans Steinbrück carried out daring anti-regime actions, including distributing anti-Nazi leaflets. Their slogans, like “So brown like shit, so brown is Cologne. Wake up!”, and crude but impactful leaflets, were designed to provoke and disrupt the carefully controlled Nazi propaganda.

The Pirates also engaged in physical confrontations with Hitler Youth patrols, clashing in street fights that asserted their autonomy. These encounters sometimes escalated to territorial skirmishes, as the Pirates resisted efforts by the Hitler Youth and Nazi police to dominate public spaces.

Brutal Nazi repression and aftermath

The Nazi response to the Edelweiss Pirates was swift and brutal. As reports of “bündische activities” (a term criminalizing youth opposition) spread, the Gestapo launched crackdowns on suspected Pirates. Many Pirates faced torture, imprisonment, and execution without trial, especially in 1942, when the Gestapo in Cologne and surrounding areas intensified arrests in response to summer leafleting campaigns by some Edelweiss groups.

One infamous incident occurred in November 1944 when thirteen youth members of the Ehrenfeld Group, including Edelweiss Pirates, were publicly executed in Cologne. Among those hanged was Barthel Schink, a teenage Pirate leader. This act of repression underscored the Nazis’ determination to root out even the smallest challenges to their authority, sending a chilling message to those who dared resist.

Even after the war, the Pirates’ struggle continued. Many survivors, particularly from working-class backgrounds, faced ongoing social stigma and were treated as criminals by post-war authorities, who dismissed their actions as delinquency rather than recognizing them as political resistance. The Edelweiss Pirates, therefore, remained marginalized in historical narratives for decades. Only in the 1980s did public recognition of their resistance begin to grow, thanks to the work of individuals like Jean Jülich and efforts to document their stories.

Belated recognition and legacy

Recognition for the Edelweiss Pirates’ resistance came late. In 1984, Jean Jülich, Michael Jovy, and Barthel Schink (posthumously) were honored as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem for their courage in helping Jews during the Nazi regime. In 2003, a memorial plaque was finally installed in Cologne’s Ehrenfeld district to commemorate those hanged in 1944. Despite initial resistance from local authorities, Cologne’s government rehabilitated the Edelweiss Pirates in 2005, officially acknowledging their role as resisters.

Memorial for the Cologne victims on Schönsteinstraße, next to the Köln-Ehrenfeld station. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Memorial for the Cologne victims on Schönsteinstraße, next to the Köln-Ehrenfeld station. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Since then, the Edelweiss Pirates have become symbols of youthful defiance against oppression. In 2005, the story of the Pirates was immortalized in the film Edelweißpiraten, and the annual Edelweiss Pirates Festival in Cologne’s Peace Park celebrates their legacy of courage. Their lives serve as reminders of the impact that nonconformity and grassroots opposition can have, even under a totalitarian regime.

The Navajos

Another prominent youth group in Cologne was the Navajos, a group named after the American Navajo people, whom they saw as symbols of freedom and resistance. The Navajos were inspired by American culture, particularly the music, style, and independence associated with the United States. They rejected the strict, authoritarian lifestyle imposed by the Nazis, instead embracing American influences in their clothing, music, and language.

The Navajos’ resistance was often cultural, expressed through forbidden dances, jazz music, and an informal dress code that contrasted with the uniformed rigidity of the Hitler Youth. Yet, like the Edelweiss Pirates, the Navajos took more direct action over time, often engaging in small acts of rebellion and providing support to those escaping Nazi persecution. Many Navajos were eventually targeted by the Gestapo, facing brutal interrogations and imprisonment. Their struggle highlights the importance of cultural resistance and the power of solidarity among youth.

Some of the non-conformist youths were willing and able to carry out politically motivated actions. In mid-September 1942, for example, slogans such as ‘Heil Navajo’ were painted on the walls of public buildings in the city center overnight.

Some of the non-conformist youths were willing and able to carry out politically motivated actions. In mid-September 1942, for example, slogans such as ‘Heil Navajo’ were painted on the walls of public buildings in the city center overnight.

Subtle and everyday acts of resistance

Beyond these well-known groups, countless other young people in Cologne engaged in subtler forms of resistance. Many refused to attend Hitler Youth meetings, listened to banned music, and celebrated cultural holidays that conflicted with Nazi ideals. They shared underground literature, spread information critical of the regime, and maintained social networks that helped marginalized individuals escape Nazi persecution. Even small gestures, such as giving food to forced laborers or avoiding Nazi events, were significant acts of defiance in a climate of repression.

For these young people, resistance often stemmed from a desire for authenticity and community rather than an overt political stance. They were united by a rejection of the oppressive, joyless world the Nazis sought to impose, driven by a desire to reclaim their personal freedom.

Legacy of youth resistance in Cologne

The youth resistance in Cologne reminds us that defiance against oppressive systems can take many forms, often outside formal or traditional frameworks. Unlike organized political movements, these youth groups operated through a mix of cultural, social, and ideological opposition, drawing strength from shared values and friendships. Their legacy is an inspiring example of the resilience of youth and their capacity to challenge authoritarianism through small, everyday acts of courage.

While many of these young resistors faced brutal consequences, their actions challenged the Nazi narrative and provided hope to others who were equally disillusioned with the regime. Their stories, preserved in institutions like the El-De Haus, serve as powerful reminders of the courage and impact that young people can have, even under the most challenging conditions.

Conclusion

Youth resistance in Cologne against the Nazi regime demonstrates the courage, creativity, and defiance of young people who rejected Nazi conformity. Whether through organized groups like the Edelweiss Pirates and the Navajos or quieter acts of personal rebellion, these youth defied an oppressive system that sought to control every aspect of their lives. Their legacy is a testament to the power of nonconformity and the importance of cultural and social freedom.

The stories of these youth resistance groups remind us of the enduring value of individual agency and collective strength. Institutions like the El-De Haus honor their memory, helping us understand the full scope of resistance against Nazi tyranny and the critical role that even the youngest citizens played in challenging injustice.

References and further reading

- Website of the NS Documentation Center El-De Hausꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Edelweiss Piratesꜛ

- NS-Dokumentationszentrum der Stadt Köln, Köln im Nationalsozialismus: Ein Kurzführer durch das ELDE Haus (NS-Dokumentation), 2010, Emons Verlag, ISBN: 978-3897052093

- Werner Jung, Bilder einer Stadt im Nationalsozialismus: Köln 1933-1945, 2016, Emons Verlag, ISBN: 9783740800147

- Horst Matzerath, Geschichte der Stadt Köln, Bd. 12: Köln in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus 1933-1945, 2009, Greven, ISBN: 978-3774304291

comments