Forgotten Victims of the Nazi regime: ‘Social Outcasts’

“Forgotten victims” are those who were ostracized and persecuted during the Nazi era, but whose suffering continued beyond 1945. Even after the Nazi defeat, these individuals remained shunned and discriminated against, denied moral recognition as victims, official rehabilitation, and financial compensation. A special exhibition in the El-De Haus pays tribute to these victim groups and their suffering. Among these groups were the so-called “asocials” – people whom the Nazi regime saw as unfit for the “national community”. In this post, I summarize their plight as conveyed through my recent visit to the El-De Haus.

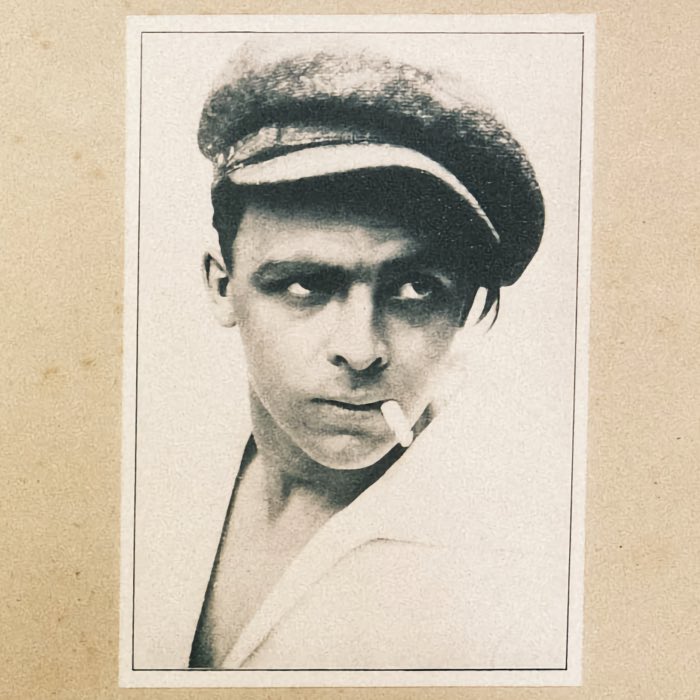

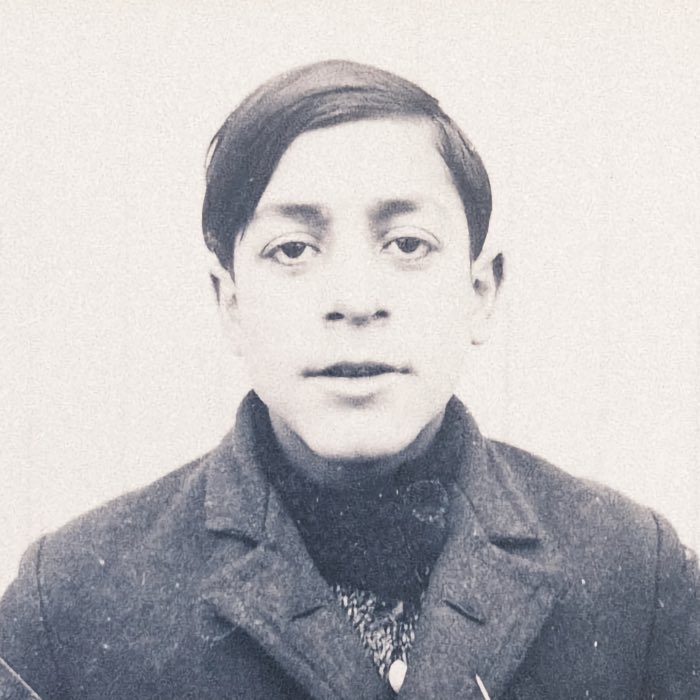

Prostitution in Holzgasse, 1907 (?). Under the Nazi rule, people accused of prostitution were often classified as “asocial” and subjected to persecution.

Prostitution in Holzgasse, 1907 (?). Under the Nazi rule, people accused of prostitution were often classified as “asocial” and subjected to persecution.

Introduction

Under the Nazi regime, a broad category of people, deemed “social outcasts” by the state, became targets of systematic persecution. The Nazis labeled these individuals “Volksschädlinge”, or “parasites on the nation”, as part of their mission to enforce a racial and social hierarchy. This category encompassed groups such as alcoholics, the homeless, the unemployed, sex workers, and others whose lifestyles or social status were seen as incompatible with Nazi ideals of “purity” and “productivity”. By targeting these individuals, the regime sought to eliminate what it considered “unworthy” elements from society, using methods that ranged from forced sterilization to incarceration, and, in extreme cases, execution.

Nazi ideology and the classification of “asocials”

The Nazi concept of “asociality” was broad and vaguely defined, allowing the regime to apply it to individuals whose existence or behavior did not conform to the values of the “Volksgemeinschaft”, or “national community”. The term covered a diverse group of people, including those who struggled with addiction, poverty, or homelessness, as well as individuals who rejected or simply failed to fit into the regime’s vision of a disciplined, obedient society. According to Nazi ideology, these individuals posed a threat to the health and strength of the German people by deviating from the supposed “norms” of behavior and productivity.

NS propaganda poster ‘Gesunde Eltern - gesunde Kinder!’ (Healthy parents - healthy children!) showing what the Nazis saw as the ideal German family.

NS propaganda poster ‘Gesunde Eltern - gesunde Kinder!’ (Healthy parents - healthy children!) showing what the Nazis saw as the ideal German family.

To enforce its agenda, the Nazi state used legislation and propaganda to cast “asocials” as a drain on society. Propaganda portrayed them as dangerous, morally corrupt individuals who needed to be controlled, reformed, or removed for the “good” of the community. This characterization justified the regime’s brutal measures and contributed to public indifference or acceptance of their persecution.

Newspaper article in the Westdeutscher Beobachter from September 20, 1933, entitled “Das Bettelwesen muss bekämpft werden” (Begging must be combated). Campaigns like this one targeted “asocials” and other marginalized groups and were aimed to incite public support for repressive measures.

Newspaper article in the Westdeutscher Beobachter from September 20, 1933, entitled “Das Bettelwesen muss bekämpft werden” (Begging must be combated). Campaigns like this one targeted “asocials” and other marginalized groups and were aimed to incite public support for repressive measures.

Forced sterilization and incarceration

The regime’s policies toward “social outcasts” were exceptionally severe. Under the “Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring”, enacted in 1933, individuals deemed “asocial” could be subject to arrest, institutionalization, or forced sterilization. Large-scale raids, such as the “beggar raid” (“Bettlerrazzia”) of September 1933 and the “Aktion Arbeitsscheu Reich” in April 1938, were carried out across the Reich to capture and detain people classified as “asocial.”

Document on the preventive police detention of a woman, 1942. Reason for arrest: classification as “asocial” and accusation of prostitution.

Document on the preventive police detention of a woman, 1942. Reason for arrest: classification as “asocial” and accusation of prostitution.

Forced sterilization was just one aspect of the Nazis’ broader eugenics program, which sought to “purify” the German population by eliminating undesirable traits. Doctors and health officials identified individuals as “unfit” based on vague, often prejudiced criteria, with little or no scientific basis. In many cases, those subjected to sterilization were given no consent or even knowledge of the procedure, which took place in state-run hospitals.

‘Erblehre und Rassenkunde in bildlicher Darstellung’ (Genetics and Racial Science in Pictorial Representation), by Alfred Vogel, 1938. The ‘Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses’ (Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily) provided for the possibility of forced sterilization in nine cases.

‘Erblehre und Rassenkunde in bildlicher Darstellung’ (Genetics and Racial Science in Pictorial Representation), by Alfred Vogel, 1938. The ‘Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses’ (Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily) provided for the possibility of forced sterilization in nine cases.

In addition to forced sterilization, thousands of people classified as “asocial” were incarcerated in workhouses, prisons, or concentration camps. Inside these facilities, detainees endured deplorable living conditions, forced labor, and abuse. For instance, women accused of prostitution or minor crimes were often sent to concentration camps under “preventive police detention”, where they faced forced labor and frequent mistreatment. These individuals, already marginalized by society, became invisible victims of the regime’s relentless drive to eliminate perceived “undesirables”.

The stigma of “asocial” status and legacy of discrimination

After the Nazi regime’s fall, individuals classified as “asocial” continued to face social stigma and discrimination. Unlike some other victim groups, they were not widely recognized or honored as victims in post-war society. Due to the lingering negative stereotypes associated with terms like “asocial”, survivors from this category often encountered rejection or marginalization even in the post-war years. For many, their experiences remained unacknowledged, and they received little or no reparations for the suffering endured under Nazi persecution.

This lingering discrimination highlights how the Nazi state’s categorization of “social outcasts” deeply embedded negative perceptions that persisted in German society. By targeting individuals who were already vulnerable, the Nazis not only deprived them of their rights but also stigmatized them in ways that endured long after the regime’s collapse.

Conclusion

The Nazi regime’s persecution of “social outcasts” reveals the extremes of its social engineering policies and the brutal lengths it pursued to create a “pure” and “productive” society. Targeting individuals who were already marginalized, the Nazis further isolated them, stripping them of their humanity and subjecting them to inhumane treatment. These forgotten victims remind us of the scope of Nazi persecution, extending beyond those traditionally included in Holocaust narratives, and underscore the devastating impact of the regime’s exclusionary ideology.

Institutions like the El-De Haus play a crucial role in bringing these overlooked stories to light. By educating the public about the fate of “social outcasts”, they ensure that the full scope of Nazi atrocities is recognized. Remembering these forgotten victims challenges us to reflect on the impacts of exclusionary ideologies and reinforces the importance of tolerance, inclusion, and human dignity in society.

References and further reading

- Website of the NS Documentation Center El-De Hausꜛ

- NS-Dokumentationszentrum der Stadt Köln, Köln im Nationalsozialismus: Ein Kurzführer durch das ELDE Haus (NS-Dokumentation), 2010, Emons Verlag, ISBN: 978-3897052093

- Werner Jung, Bilder einer Stadt im Nationalsozialismus: Köln 1933-1945, 2016, Emons Verlag, ISBN: 9783740800147

- Horst Matzerath, Geschichte der Stadt Köln, Bd. 12: Köln in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus 1933-1945, 2009, Greven, ISBN: 978-3774304291

- Hans Peter Richter, Damals war es Friedrich: Roman, 1979, dtv Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG, ISBN: 978-3423078009.

comments