Forgotten victims of the Nazi regime: Roma and Sinti

“Forgotten victims” are those who were ostracized and persecuted during the Nazi era, but whose suffering continued beyond 1945. Even after the Nazi defeat, these individuals remained shunned and discriminated against, denied moral recognition as victims, official rehabilitation, and financial compensation. A special exhibition in the El-De Haus pays tribute to these victim groups and their suffering. The group of Roma and Sinti was one of these forgotten victims. In this post, I summarize their plight as conveyed through my recent visit to the El-De Haus.

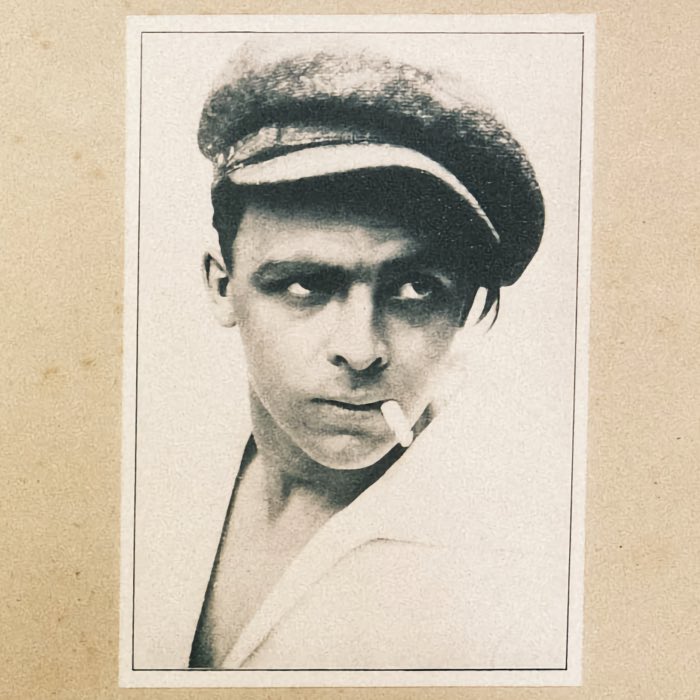

The family Reinhardt. The Reinhardts were among the countless Roma and Sinti families targeted by the Nazis in their campaign of persecution and extermination. Nazi propaganda often dehumanized these communities, reducing their lives to numbers and statistics to rationalize discrimination and, eventually, mass murder. However, the stories of families like the Reinhardts remind us that behind each “number” were individual lives, dreams, and loved ones. Recognizing this human dimension challenges us to confront the full tragedy of Nazi crimes, ensuring that the suffering of Roma and Sinti families is remembered with the dignity and respect they were denied in life.

The family Reinhardt. The Reinhardts were among the countless Roma and Sinti families targeted by the Nazis in their campaign of persecution and extermination. Nazi propaganda often dehumanized these communities, reducing their lives to numbers and statistics to rationalize discrimination and, eventually, mass murder. However, the stories of families like the Reinhardts remind us that behind each “number” were individual lives, dreams, and loved ones. Recognizing this human dimension challenges us to confront the full tragedy of Nazi crimes, ensuring that the suffering of Roma and Sinti families is remembered with the dignity and respect they were denied in life.

Introduction

Among the many groups persecuted by the Nazi regime, the Roma and Sinti communities endured severe discrimination, brutality, and mass extermination. Targeted for their ethnic background, they were labeled as “racially inferior” and subjected to policies of exclusion, internment, forced sterilization, and genocide. The persecution of Roma and Sinti, often referred to as the “Porajmos”, or “the Devouring”, represents a critical yet often underrepresented chapter in the broader narrative of Nazi atrocities. Through this examination, we honor the memory of Roma and Sinti victims and recognize the extensive suffering they endured.

The Nazi racial ideology and the marginalization of Roma and Sinti

From the earliest days of Nazi rule, Roma and Sinti were marked for persecution under the regime’s racial ideology, which viewed them as “undesirable” and “genetically inferior.” Nazi officials categorized Roma and Sinti as “alien” groups whose presence was considered a threat to the “purity” and “strength” of the Aryan race. Rooted in eugenic theories that viewed the Roma lifestyle and cultural heritage as incompatible with the Nazis’ vision of an ordered society, this racial prejudice laid the groundwork for systematic discrimination and eventual genocide.

The initial wave of anti-Roma policies mirrored those enacted against Jews, including exclusion from public life, restriction of movement, and social ostracization. In 1936, on the eve of the Olympics, the Nazi regime forcibly relocated Roma and Sinti from Berlin and other cities to isolated camps, a move intended to “cleanse” urban areas of populations they deemed undesirable. These measures soon expanded to the forced registration, medical examination, and surveillance of all Roma and Sinti in Germany, culminating in nationwide policies designed to isolate, control, and ultimately eliminate these communities.

File card of Anton Reinhardt, a Roma individual documented by Nazi officials. Systematic record-keeping enabled the regime to track and target members of the Roma and Sinti communities for persecution.

File card of Anton Reinhardt, a Roma individual documented by Nazi officials. Systematic record-keeping enabled the regime to track and target members of the Roma and Sinti communities for persecution.

Forced sterilization and internment

As with other groups deemed “unfit” by Nazi ideology, forced sterilization was used as a means of eradicating future generations of Roma and Sinti. Many Roma and Sinti were brought before the Hereditary Health Courts, where their sterilization was mandated under the “Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring.” In some cases, sterilization was carried out without any legal process or consent, often under the pretense of minor medical procedures. Thousands of Roma and Sinti were sterilized under these policies, stripping them of their reproductive rights and violating their bodily autonomy.

Simultaneously, Roma and Sinti were confined to internment camps. In many regions, local authorities established “Gypsy camps” where families were forced to live under appalling conditions. In Cologne, for instance, the Schwarz-Weiß-Platz camp served as a holding facility for Roma and Sinti families who were deprived of basic human needs and subjected to constant surveillance. These internment sites isolated Roma and Sinti from the general population, facilitating later mass deportations to extermination camps.

Due to its proximity to the sports field of the Schwarz-Weiß Köln club in Cologne-Bickendorf, Venloer Straße 888, the camp was given the name ‘Schwarz-Weiß-Platz’. The local criminal investigation department, which had set up its own ‘Department for Gypsy Affairs’, was responsible for monitoring and persecuting the Sinti and Roma.

Due to its proximity to the sports field of the Schwarz-Weiß Köln club in Cologne-Bickendorf, Venloer Straße 888, the camp was given the name ‘Schwarz-Weiß-Platz’. The local criminal investigation department, which had set up its own ‘Department for Gypsy Affairs’, was responsible for monitoring and persecuting the Sinti and Roma.

The Porajmos: Genocide of Roma and Sinti

The Nazi regime’s policies escalated into systematic genocide with the mass deportation of Roma and Sinti to concentration and extermination camps across occupied Europe. Between 1939 and 1945, thousands of Roma and Sinti were deported from Germany and territories under Nazi control to camps such as Auschwitz-Birkenau, where they were held in a designated “Gypsy camp.” Here, entire families — including men, women, and children — faced starvation, forced labor, brutal medical experiments, and eventual murder.

On August 2, 1944, one of the most infamous episodes in the genocide of the Roma and Sinti took place. That night, the SS liquidated the “Gypsy camp” at Auschwitz-Birkenau, murdering approximately 4,300 men, women, and children in the gas chambers. Known as Zigeunernacht (“Gypsy Night”), this event has come to symbolize the broader suffering and devastation endured by Roma and Sinti communities under Nazi rule. Historians estimate that between 220,000 and 500,000 Roma and Sinti were murdered during the Porajmos, though the exact number remains unknown due to limited records and the marginalization of this history for decades after the war.

Deportation of children during the ‘Great Lockdown’ in September 1942. Roma and Sinti families, including young children, were systematically deported from their homes to concentration camps, where most faced death.

Deportation of children during the ‘Great Lockdown’ in September 1942. Roma and Sinti families, including young children, were systematically deported from their homes to concentration camps, where most faced death.

Legacy and recognition of the Roma and Sinti genocide

In the decades following the war, the genocide of Roma and Sinti was largely overlooked by both German authorities and the international community. Unlike other victim groups, Roma and Sinti survivors received little recognition or compensation, and public awareness of their persecution remained limited. This neglect compounded the trauma experienced by survivors and reinforced the stigma and discrimination Roma and Sinti communities already faced.

Only in recent decades has the Porajmos gained wider acknowledgment. In 1982, the West German government officially recognized the genocide of Roma and Sinti, and since then, memorials and commemorations have been established to honor the memory of the victims. In Berlin, the Memorial to the Sinti and Roma Victims of National Socialism, opened in 2012, stands as a testament to their suffering and serves as a reminder of the human cost of racial prejudice and genocide.

Conclusion

The suffering of Roma and Sinti under Nazi rule is a poignant reminder of the dangers posed by racial and ethnic discrimination. Targeted for their heritage and way of life, they were subjected to a brutal campaign of persecution and extermination that remains one of the darkest chapters in Nazi history. Acknowledging the Porajmos is essential to fully understanding the scope of Nazi atrocities and honoring the memory of those who endured unimaginable suffering.

Institutions like the El-De Haus and initiatives that promote awareness of the Roma and Sinti genocide play a critical role in preserving this history. By educating future generations about the consequences of hatred and intolerance, we affirm our commitment to justice and human rights for all, ensuring that the memory of these forgotten victims endures.

References and further reading

- Website of the NS Documentation Center El-De Hausꜛ

- NS-Dokumentationszentrum der Stadt Köln, Köln im Nationalsozialismus: Ein Kurzführer durch das ELDE Haus (NS-Dokumentation), 2010, Emons Verlag, ISBN: 978-3897052093

- Werner Jung, Bilder einer Stadt im Nationalsozialismus: Köln 1933-1945, 2016, Emons Verlag, ISBN: 9783740800147

- Horst Matzerath, Geschichte der Stadt Köln, Bd. 12: Köln in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus 1933-1945, 2009, Greven, ISBN: 978-3774304291

- Hans Peter Richter, Damals war es Friedrich: Roman, 1979, dtv Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG, ISBN: 978-3423078009.

comments