Acts of resistance in Cologne against the Nazi regime

The Nazi regime sought to establish absolute control over Germany, enforcing its ideology through propaganda, legislation, and violence. Despite the immense risks, individuals and groups across the country resisted, determined to oppose oppression and fight for a more just society. Cologne, a historic city with a strong sense of community, became a focal point for numerous resistance efforts. This article explores some of the diverse acts of defiance in Cologne, where individuals from various backgrounds and beliefs stood against the Third Reich, often at great personal cost. Much of this information is based on sources provided by the NS Documentation Center, El-De Haus in Cologne, which I visited recently.

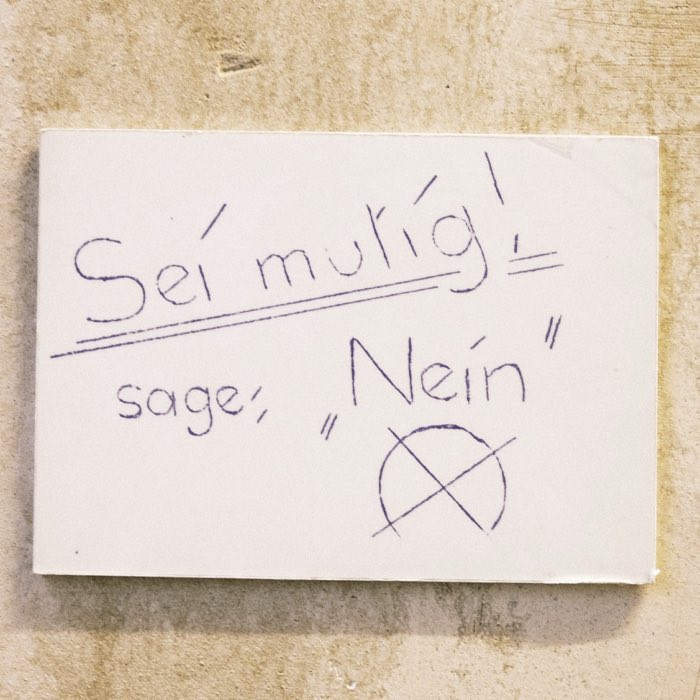

Protest graffiti by a Catholic youth group, 1942.

Protest graffiti by a Catholic youth group, 1942.

Civilian resistance and small acts of defiance

Resistance in Cologne took many forms, from organized movements to smaller, personal acts of defiance. Many citizens found ways to express their opposition to the Nazi regime, even if these acts were less visible than larger uprisings or armed resistance. Simple yet meaningful gestures included refusing to give the “Heil Hitler” salute, offering shelter to persecuted individuals, and spreading anti-Nazi sentiments through conversation or graffiti.

The resistance groups used the spoken and written word almost exclusively as a form of political struggle. In addition to writing situation reports, which found their way into publications abroad, and distributing leaflets and anonymous flyers, camouflage pamphlets smuggled in from abroad were mainly used to inform people about the true nature of the regime.

The resistance groups used the spoken and written word almost exclusively as a form of political struggle. In addition to writing situation reports, which found their way into publications abroad, and distributing leaflets and anonymous flyers, camouflage pamphlets smuggled in from abroad were mainly used to inform people about the true nature of the regime.

One of the most significant civilian forms of resistance was hiding or aiding Jewish neighbors, friends, and other persecuted groups. Many individuals in Cologne provided food, shelter, and false identification documents, risking their own lives to protect those targeted by the Nazis. While these acts might seem small in scale, they exemplify the courage and compassion that many ordinary Germans displayed, quietly resisting the regime’s dehumanizing policies.

Karl Küpper: The carnival jester who defied the Nazis

The book printer Karl Küpper (1905-1970) was a local celebrity in Cologne’s carnival and known as ‘Dr Verdötschte’. Carnival in Cologne began to come to terms with the Nazi regime after 1933, but Karl made no secret of his distanced stance towards the Nazi regime. He displayed this subtly but clearly in his performances. He soon stopped participating in radio broadcasts with the explanation: “Die dunn do immer su komisch ‘Hallo’ roofe” (“They always shout hello so strangely”), an allusion to the Hitler salute. He also satirized it on stage. When he entered, he often raised his right arm and said to the surprise of the audience: “Su huh litt bei uns dr Dreck em Keller!” (“That’s how high the dirt is in our cellar!””). Initially, his popularity secured him further appearances, until he was banned from speaking in February 1939 and ordered to report regularly to the Gestapo. He escaped further sanctions by enlisting in the Wehrmacht. After 1945, Karl Küpper renounced a major career.

National Committee for a Free Germany

As the defeat of the German troops became apparent in 1943, individuals and a few small, scattered groups came together to engage in resistance activities. In the Cologne group of the National Committee for a Free Germany, the largest resistance group during the war, social democrats, Christians and commoners worked together with communists against the Nazi regime. The communists Engelbert Brinker, Otto Richter and Wilhelm Tollmann were among the founding members of the National Committee Free Germany in Cologne. They were arrested by the Gestapo during their attack on the Klettenberg group of the National Committee in November 1944 and were tortured during interrogation in the El-De House and in Brauweiler to such an extent that they died there. The photo below shows the stairwell at Sülzgürtel 8. The Humbach family’s apartment at Sülzgürtel 8 served as the National Committee’s contact point. The entire management was arrested here by the Gestapo in November 1944.

Staircase Sülzgürtel 8, Cologne.

Staircase Sülzgürtel 8, Cologne.

Franz Vonessen

Franz Vonessen (1892-1970) was the head city doctor at Cologne’s health department from 1929. As a member of the Center Party, he suffered professional disadvantages from 1933 onwards. After refusing to cooperate in the implementation of the ‘Law for the Prevention of Hereditary Diseases’ out of religious conviction, he was retired in 1936. Despite his stance against the Nazi racial laws, he was able to set up as a doctor and run a private practice until the end of 1944. Despite the ban, he also treated Jews and other persecuted people, hiding some of them and providing them with food stamps and false papers. On May 1, 1945, the American military government appointed Franz Vonessen head of the Cologne health department.

Bishop Clemens August von Galen

The Catholic Church, while generally cautious under Nazi rule, became a voice of resistance in certain areas, especially regarding the regime’s Aktion T4 euthanasia program. The T4 program targeted disabled individuals, whom the Nazis deemed “life unworthy of life”, leading to the systematic killing of tens of thousands. In 1941, Bishop Clemens August von Galen of Münster delivered powerful sermons condemning the murders of disabled people, calling these acts an affront to Christian values and human dignity.

While von Galen’s protests initially focused on Münster, his influence resonated across the Rhineland, inspiring members of the Cologne Catholic community to oppose Nazi policies. Some clergy members in Cologne spread von Galen’s sermons clandestinely, and a network of sympathetic priests and laypeople emerged to help protect vulnerable individuals, share anti-Nazi messages, and encourage moral resistance.

Catholic workers’ associations

In Cologne, from the mid-1930s onwards, clergy and lay functionaries of the Catholic workers’ movement, the Kolping family and Rhenish centrist politicians held conspiratorial meetings in the Kettelerhaus, later also in the Kolpinghaus in Breite Straße. The members of the discussion group in the Kettelerhaus were part of the extended resistance circle from among which Count Stauffenberg carried out an assassination attempt on Hitler on July 20, 1944. Most of the members of this circle were arrested by the Gestapo in August 1944 as part of the so-called Operation Thunderstorm and initially imprisoned in the Deutzer Messe or in the El-De Haus.

Association headquarters of the Catholic workers’ associations of West Germany, Kettelerhaus, Odenkirchener Straße 26 (today Bernhard-Letterhaus-Straße), ca. 1929.

Association headquarters of the Catholic workers’ associations of West Germany, Kettelerhaus, Odenkirchener Straße 26 (today Bernhard-Letterhaus-Straße), ca. 1929.

Georg Fritze

Georg Fritze had been a Protestant pastor in Cologne since 1916. He was one of the founding members of the group of religious socialists in 1920 and joined the Confessing Church (an opposition movement within the Protestant Church) after 1933. In 1938, he refused to swear allegiance to Hitler and was subsequently (forcibly) suspended. He died a short time later.

Georg Fritze (1874-1939), 1938.

Georg Fritze (1874-1939), 1938.

Youth resistance movements: The Edelweiss Pirates

Cologne was also home to youth resistance groups who rejected the strict conformity and militarization imposed by the Hitler Youth. One of the most famous of these groups was the Edelweiss Pirates, a loosely organized network of young people who embraced independence, defied Nazi norms, and openly resisted the regime. The Pirates, many of whom were working-class youth, developed their own subculture, characterized by distinctive clothing, gatherings, and music that contrasted sharply with the rigid discipline of the Hitler Youth.

The Edelweiss Pirates’ resistance evolved from subtle nonconformity to active defiance. They would disrupt Hitler Youth activities, distribute anti-Nazi leaflets, and assist Allied forces by providing intelligence or sheltering escaped prisoners and Jews. In 1944, the Ehrenfeld Group, a particularly radical faction of the Edelweiss Pirates led by Hans Steinbrück, engaged in direct attacks against Nazi officials and collaborators. In response, the Gestapo launched a brutal crackdown on the Pirates, resulting in public executions of several members, including Barthel Schink, a teenage leader. The Edelweiss Pirates’ courage and defiance symbolize the spirit of youth resistance in Nazi Germany.

Edelweiss Pirates in Beethoven Park, 1943. Their gatherings, music, and nonconformist behavior represented a form of cultural resistance.

Edelweiss Pirates in Beethoven Park, 1943. Their gatherings, music, and nonconformist behavior represented a form of cultural resistance.

Resistance from the Left: The Communist and Socialist underground

In Cologne, left-wing resistance movements also mobilized against the Nazis, often led by members of the Communist Party (KPD) and the Social Democratic Party (SPD), both of which were outlawed after Hitler’s rise to power. These activists worked clandestinely, organizing underground networks that spread anti-Nazi literature, encouraged worker strikes, and coordinated sabotage efforts. Despite the severe risks, Cologne’s Communist and Socialist activists remained committed to their ideals and their opposition to fascism.

Election posters against Hitler, before 1933.

Election posters against Hitler, before 1933.

The Communist resistance, particularly active in working-class neighborhoods, established networks that gathered information, spread anti-Nazi propaganda, and assisted forced laborers. The Socialist and Communist resistance groups faced constant surveillance from the Gestapo, which frequently infiltrated and dismantled their networks, leading to arrests, imprisonment, and executions. Despite these challenges, their courage and dedication were critical components of Cologne’s resistance landscape.

Communists and Social Democrats hid their protest messages in disguised writings.

Communists and Social Democrats hid their protest messages in disguised writings.

Student resistance: The Kreisau Circle and the White Rose

Though based primarily in Munich, the White Rose resistance group, led by students Hans and Sophie Scholl, inspired student opposition across Germany, including in Cologne. The White Rose’s leaflets, denouncing the brutality and hypocrisy of the Nazi regime, were smuggled to cities throughout Germany, including Cologne, where they were read by students, intellectuals, and ordinary citizens.

In addition, the Kreisau Circle, an intellectual resistance group that included former Prussian aristocrats, lawyers, and theologians, sought to outline plans for a post-Nazi Germany rooted in democratic and Christian values. The Kreisau Circle’s ideas and publications reached supporters in Cologne, where members of the educated middle class shared a commitment to envisioning an alternative future. Though these groups were not based in Cologne, their ideas resonated with many within the city, providing hope and fostering moral resistance among students and professionals.

Clerical and lay assistance to Jews

The Catholic and Protestant communities in Cologne also played a significant role in aiding Jews. In addition to sheltering individuals, they sometimes organized escape routes, provided forged documents, and distributed food rations to Jewish families hiding from Nazi authorities. Many priests and laypeople risked arrest, and several were detained or executed for their involvement in these activities.

In response to the National Socialist attacks, the German Bishops’ Conference set up the “Defense Office against Anti-Christian Propaganda” in Cologne in 1934, which was headed by the cathedral vicar Josef Teusch. In the following years, this office distributed around 20 brochures in the German Reich with a total circulation of around 17 million copies. Confessional pamphlets were also published within the Protestant church to ward off National Socialist attacks.

In response to the National Socialist attacks, the German Bishops’ Conference set up the “Defense Office against Anti-Christian Propaganda” in Cologne in 1934, which was headed by the cathedral vicar Josef Teusch. In the following years, this office distributed around 20 brochures in the German Reich with a total circulation of around 17 million copies. Confessional pamphlets were also published within the Protestant church to ward off National Socialist attacks.

Gertrud Koch, a young Catholic woman affiliated with the Edelweiss Pirates, was especially active in these efforts. After her father was killed in the concentration camps, Koch dedicated herself to assisting Jews and other persecuted individuals, coordinating with fellow Edelweiss members to offer shelter and supplies.

Artworks

Gerd Arntz, born in Remscheid in 1900, belonged to the Cologne Progressive artists’ group in the 1920s. He worked in Vienna from 1928. In 1934 he emigrated to The Hague. In 1936, an enlargement of this graphic was shown in Amsterdam at the exhibition “De Olympiade Onder Dictatuur”. It had to be removed at the insistence of the German removed at the insistence of the German embassy.

“Das Dritte Reich” by Gerd Arntz. Screen print from 1978 after the woodcut from 1934.

“Das Dritte Reich” by Gerd Arntz. Screen print from 1978 after the woodcut from 1934.

In February 1938, while residing in Antwerp, Karl Schwesig created a satirical ink drawing. This artwork, part of a collection of eight similar pieces, depicted a skeletal figure with Adolf Hitler’s face entering Cologne’s ablaze railway station. These drawings were meant for the Kölner Rosenmontags-Zeitung (Cologne Rose Monday Newspaper), an underground publication. Printed in Cologne, this newspaper was distributed during the city’s Carnival celebrations on Rose Monday, shortly before Lent in early 1938. The original drawings, however, never left Germany due to the risks involved in smuggling them out. They remained stored in the printer’s shop, where they suffered damage from a wartime fire. Schwesig’s life took a tumultuous turn after Hitler’s rise to power in January 1933. Being a Communist, he was arrested and spent 16 months in prison. Released in 1935, he found refuge in Antwerp, Belgium. However, with the German invasion of Belgium on May 10, 1940, Schwesig’s safety was again compromised. He was arrested and taken to Vichy France, enduring confinement in various internment camps. In 1943, Schwesig was transferred to the Ulmer Hoeh prison in Dusseldorf, only to be freed by American forces in April 1945.

“Daß wir hier in Flammen aufgehen verdanken wir dem Führer!” by Karl Schwesig, 1938.

“Daß wir hier in Flammen aufgehen verdanken wir dem Führer!” by Karl Schwesig, 1938.

The legacy of Cologne’s resistance

The diverse acts of resistance in Cologne illustrate the courage of individuals who, despite facing severe consequences, chose to stand against tyranny. From the outspoken condemnation by the Catholic Church of the Nazi euthanasia program to the Edelweiss Pirates’ rebellious spirit and the underground activism of Communists and Socialists, Cologne’s resistance spanned social classes, political beliefs, and age groups.

After the war, recognition of these resistance efforts was slow, and many survivors continued to face prejudice, particularly members of the Edelweiss Pirates, who were often seen as juvenile delinquents rather than as resistors. Over time, however, the bravery of Cologne’s resisters has been acknowledged and honored, with memorials and ceremonies ensuring that their stories are not forgotten.

Conclusion

The acts of resistance in Cologne demonstrate that opposition to Nazi rule was not confined to any one ideology or demographic. Whether through civil disobedience, intellectual resistance, or direct confrontation, the people of Cologne displayed remarkable resilience and courage. Their legacy is a testament to the power of solidarity and moral conviction, reminding us of the importance of resisting oppression, even in the face of overwhelming danger.

Today, institutions like the El-De Haus, which was once a Gestapo headquarters, serve as memorials, preserving the memory of those who dared to oppose one of history’s most oppressive regimes. By commemorating these acts of resistance, we honor those who risked everything to defend freedom and human dignity, and we inspire future generations to remain vigilant against the forces of oppression and injustice.

References and further reading

- Website of the NS Documentation Center El-De Hausꜛ

- NS-Dokumentationszentrum der Stadt Köln, Köln im Nationalsozialismus: Ein Kurzführer durch das ELDE Haus (NS-Dokumentation), 2010, Emons Verlag, ISBN: 978-3897052093

- Werner Jung, Bilder einer Stadt im Nationalsozialismus: Köln 1933-1945, 2016, Emons Verlag, ISBN: 9783740800147

- Horst Matzerath, Geschichte der Stadt Köln, Bd. 12: Köln in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus 1933-1945, 2009, Greven, ISBN: 978-3774304291

comments