Persecution of homosexuals under the Nazi regime

“Forgotten victims” are those who were ostracized and persecuted during the Nazi era, but whose suffering continued beyond 1945. Even after the Nazi defeat, these individuals remained shunned and discriminated against, denied moral recognition as victims, official rehabilitation, and financial compensation. A special exhibition in the El-De Haus pays tribute to these victim groups and their suffering. Homosexuals were one of the groups that were persecuted. In this post, I summarize their plight as conveyed through my recent visit to the El-De Haus.

Evidence of homosexual life and culture in Cologne before 1933. The magazine Der Eigene, published before the Nazi era, was the world’s first homosexual magazine and a hub for progressive thought on sexuality. Its existence reflects the early 20th century’s initial advances in homosexual rights, which were quickly reversed by the Nazis.

Evidence of homosexual life and culture in Cologne before 1933. The magazine Der Eigene, published before the Nazi era, was the world’s first homosexual magazine and a hub for progressive thought on sexuality. Its existence reflects the early 20th century’s initial advances in homosexual rights, which were quickly reversed by the Nazis.

Introduction

Homosexuals were among the many groups targeted by the Nazi regime in its quest for a “pure” and “disciplined” society. Under the guise of restoring “moral order”, the Nazis enacted a campaign of systemic persecution, focusing primarily on gay men. This campaign was marked by arrests, forced labor, imprisonment, torture, and murder. The persecution of homosexuals, particularly men, reflects the regime’s determination to control private life and enforce a strict, heteronormative social order. Remembering this aspect of Nazi history reminds us of the dangers of state-sanctioned homophobia and the far-reaching impact of policies that criminalize sexual orientation.

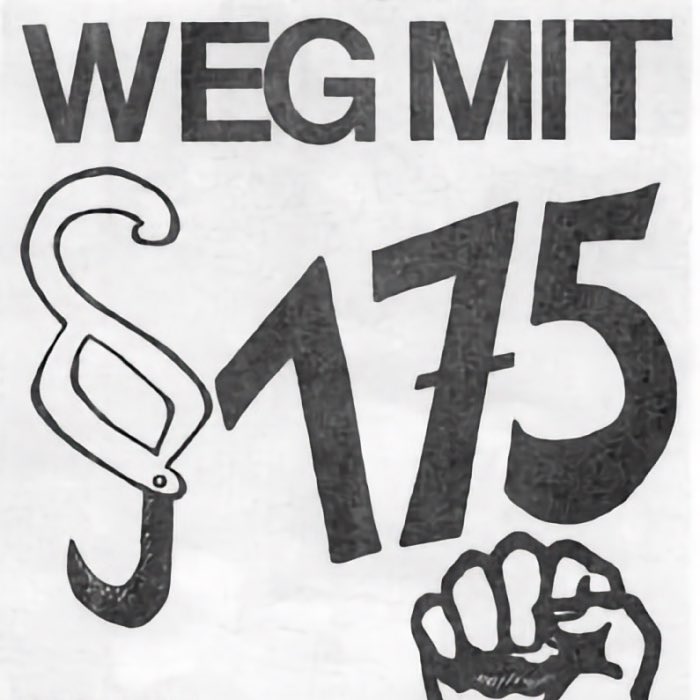

Criminalization and intensification of Paragraph 175

Homosexuality was already criminalized in Germany before the Nazi era under Paragraph 175 of the German Penal Code, which made “unnatural fornication” between men punishable by law. However, the Nazi regime significantly intensified this legislation in 1935, broadening the definition of punishable acts to include any perceived homosexual behavior, even if it involved non-physical gestures or private associations. According to National Socialist racial ideology, homosexuality was regarded as a “plague” that led to a “weakening of the people’s strength”, as homosexuals were seen as deviating from the “natural reproductive process.” This view fueled the tightening of Paragraph 175, with local criminal police conducting investigations and bringing hundreds of cases to trial, especially in cities like Cologne.

Most court cases ended with prison sentences, though the worst consequences included forced castration and deportation to concentration camps. In Cologne, hundreds of gay men faced prison and penitentiary sentences, with some dying in camps or being executed in Klingelpütz prison. The regime’s drive to control and eliminate homosexuality illustrates its broader attempt to regulate private life, sexual behavior, and reproduction, enforcing a strict conformity that was framed as essential for national unity.

Imprisonment and concentration camps

Men convicted under Paragraph 175 often faced prison sentences, but thousands were sent to concentration camps, where they endured some of the harshest conditions. Marked with a pink triangle, homosexual prisoners were not only forced into hard labor but were also subjected to brutal treatment and medical experiments aimed at “curing” or “correcting” their sexual orientation. Many did not survive, succumbing to overwork, starvation, abuse, or direct execution.

Document of the police preventive detention of a homosexual in 1943. Marked for “attempted seduction of males under the age of 21”, many men faced detention under Paragraph 175 without evidence beyond hearsay.

Document of the police preventive detention of a homosexual in 1943. Marked for “attempted seduction of males under the age of 21”, many men faced detention under Paragraph 175 without evidence beyond hearsay.

In concentration camps, gay men were frequently ostracized by other prisoners and were often chosen for particularly severe medical experiments, including forced castration. This dehumanizing treatment underscored the regime’s view of homosexuality as a threat to the racial and moral fabric of German society, which, in their ideology, justified any extreme measure to “eliminate” this perceived threat.

The so-called “Rosa Winkel” (pink triangle) was used to mark concentration camp prisoners persecuted for their homosexuality. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: public domain).

The broader impact of Nazi homophobia

The Nazi regime’s assault on homosexuals extended beyond direct victims to German society as a whole, instilling a climate of fear and repression that discouraged any expression of non-conformity. LGBTQ+ culture, which had been gaining visibility in pre-Nazi Germany, was forced underground, and many people concealed or denied their sexual orientation to avoid detection.

The persecution also had long-term legal and social repercussions. After the war, Paragraph 175 remained in effect in West Germany, continuing the criminalization of male homosexuality. Many survivors of Nazi persecution remained silent due to societal stigma, and unlike other groups targeted by the Nazis, gay men were denied reparations or official recognition as victims. The continuity of Paragraph 175 until 1969, and its full repeal only in 1994, reflects the enduring influence of Nazi-era homophobia on post-war German society.

Women and the “asocial” category

The Nazi persecution of homosexuality focused on men, but some lesbian women were also targeted, though not under Paragraph 175. Because lesbianism did not affect the Nazi focus on male productivity and reproduction in the same direct way, women were typically not prosecuted as criminals. However, lesbian women were frequently categorized as “asocial” and were sent to concentration camps under the broad classification of social deviants. In these camps, they wore the black triangle, which denoted individuals deemed nonconformists, including homeless individuals, sex workers, and “work-shy” people.

Advertisements of Cologne homosexual venues before 1933. Before the Nazi era, Germany saw a flourishing LGBTQ+ culture with venues, publications, and social networks that provided visibility and support for the community. This progress was swiftly undone by Nazi persecution.

Advertisements of Cologne homosexual venues before 1933. Before the Nazi era, Germany saw a flourishing LGBTQ+ culture with venues, publications, and social networks that provided visibility and support for the community. This progress was swiftly undone by Nazi persecution.

In Cologne and elsewhere, women labeled as asocials were often subjected to forced labor and harsh treatment, even though their cases were not prosecuted through Paragraph 175. This form of persecution reflects the regime’s rigid enforcement of gender roles, where women who did not conform to the ideals of motherhood and domesticity faced punishment and persecution.

Recognition and memory of LGBTQ+ victims

For decades after the Nazi regime’s fall, the persecution of homosexuals remained a hidden chapter of Holocaust history. Survivors of Paragraph 175 often faced continued legal repercussions and societal prejudice, leading many to remain silent about their experiences. It was not until the 1980s that broader awareness of the Nazi persecution of homosexuals began to emerge, thanks to LGBTQ+ activists and historians who brought attention to their plight.

In 2002, the German government issued an official apology to homosexuals persecuted under Nazi rule and posthumously pardoned those convicted under Paragraph 175. Memorials, including the pink triangle symbol, now serve as reminders of the Nazi regime’s assault on LGBTQ+ individuals and as calls for vigilance against homophobia.

Conclusion

The Nazi persecution of homosexuals reveals the regime’s ruthless enforcement of a narrow, heteronormative vision for society and the catastrophic effects of state-sanctioned homophobia. Gay men and, to a lesser extent, lesbian women, were stripped of their rights, brutalized, and, in many cases, murdered because their identities did not conform to Nazi ideals. This chapter of history underscores the devastating impact of discrimination based on sexual orientation, reminding us of the importance of protecting human rights and dignity for all.

Angular memorial plaques made of red granite with the inscription “Totgeschlagen, totgeschwiegen” (Beaten to death, kept silent) were placed at various memorial sites, here at Nollendorfplatz subway station in Berlin. Source: Wikimedia Commonsꜛ (license: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Institutions like the El-De Haus honor the memory of LGBTQ+ individuals who suffered under Nazi rule, ensuring that their stories are not forgotten. By acknowledging the full scope of Nazi persecution, we gain a deeper understanding of the dangers of intolerance and the necessity of safeguarding inclusivity and acceptance.

References and further reading

- Website of the NS Documentation Center El-De Hausꜛ

- NS-Dokumentationszentrum der Stadt Köln, Köln im Nationalsozialismus: Ein Kurzführer durch das ELDE Haus (NS-Dokumentation), 2010, Emons Verlag, ISBN: 978-3897052093

- Werner Jung, Bilder einer Stadt im Nationalsozialismus: Köln 1933-1945, 2016, Emons Verlag, ISBN: 9783740800147

- Horst Matzerath, Geschichte der Stadt Köln, Bd. 12: Köln in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus 1933-1945, 2009, Greven, ISBN: 978-3774304291

- Wikipedia article on Homosexuality durign the Nazi regimeꜛ

- Wikipedia article on the Rosa Winkelꜛ

comments