Forgotten victims of the Nazi regime: Disabled individuals

“Forgotten victims” are those who were ostracized and persecuted during the Nazi era, but whose suffering continued beyond 1945. Even after the Nazi defeat, these individuals remained shunned and discriminated against, denied moral recognition as victims, official rehabilitation, and financial compensation. A special exhibition in the El-De Haus pays tribute to these victim groups and their suffering. Disabled individuals were among the groups that were persecuted. In this post, I summarize their plight as conveyed through my recent visit to the El-De Haus.

Court building on Reichenspergerplatz: seat of the Hereditary Health Court and the Higher Hereditary Health Court

Court building on Reichenspergerplatz: seat of the Hereditary Health Court and the Higher Hereditary Health Court

Introduction

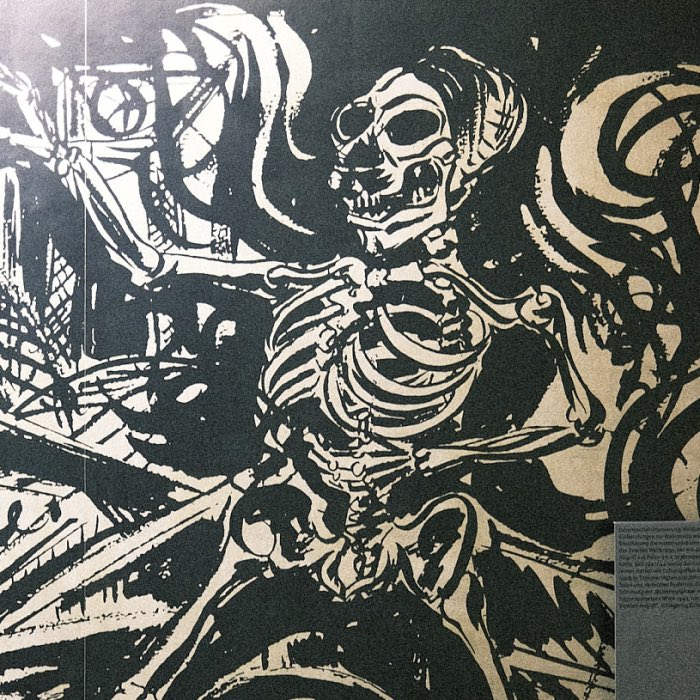

Among the groups targeted by the Nazi regime’s eugenics policies, individuals with disabilities faced particularly brutal persecution. Branded as “life unworthy of life” (“lebensunwertes Leben”) by Nazi ideology, people with physical and mental disabilities were seen as a burden to society and subjected to the regime’s systematic violence. Under the guise of public health and “racial hygiene”, the Nazis implemented programs that sought to “cleanse” the population of individuals they deemed genetically “defective.” These policies culminated in the T4 Euthanasia Program, a horrific campaign that led to the murder of tens of thousands of disabled individuals and laid the groundwork for the broader atrocities of the Holocaust.

The roots of Nazi eugenics and the targeting of disabilities

The Nazis’ views on disability were grounded in their broader eugenics agenda, which aimed to create a “pure” and “productive” German race. People with disabilities were viewed as threats to this ideal, as the regime believed they represented genetic “flaws” that could weaken future generations. In pursuit of this ideological goal, the Nazi government enacted the “Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring” on July 14, 1933, which provided legal grounds for forced sterilization in nine specific cases, including schizophrenia, epilepsy, blindness, deafness, and severe physical deformities.

‘Erblehre und Rassenkunde in bildlicher Darstellung’ (Genetics and Racial Science in Pictorial Representation), by Alfred Vogel, 1938. The ‘Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses’ (Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily) provided for the possibility of forced sterilization in nine cases.

‘Erblehre und Rassenkunde in bildlicher Darstellung’ (Genetics and Racial Science in Pictorial Representation), by Alfred Vogel, 1938. The ‘Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses’ (Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily) provided for the possibility of forced sterilization in nine cases.

Under this law, doctors and officials at health institutions were required to identify and report individuals they deemed unfit, often relying on prejudiced assessments or limited family histories. Requests for sterilization were processed by specialized courts, including the Hereditary Health Court and, in appeals, the Higher Hereditary Health Court, which reviewed cases and decided on sterilization applications. Doctors from the Advisory Office for Hereditary and Racial Care of the Health Department contributed expert opinions to these proceedings, lending a facade of scientific legitimacy to an ethically abhorrent policy.

The sterilizations were carried out in hospitals, including institutions such as Lindenburg University Hospital and the Weyertal Protestant Hospital, both of which were sites for the forced sterilization of over 2,000 individuals in Cologne alone. Nationwide, the policy resulted in an estimated 400,000 forced sterilizations, often without the victims’ consent or understanding of the procedure. This state-sponsored sterilization, presented as a public health measure, was a foundational step in the regime’s escalating oppression of disabled individuals and other groups deemed “undesirable.”

The T4 euthanasia program: Mass murder of disabled individuals

The Nazis escalated their policies against people with disabilities through the “Aktion T4”, or T4 Euthanasia Program, which began in 1939. Named after the address of its Berlin headquarters, Tiergartenstraße 4, the T4 program was a secret initiative aimed at the mass murder of disabled individuals whom the Nazis deemed “incurable” or “burdensome.” The program initially targeted disabled children and then expanded to adults, particularly those living in institutional care facilities.

The “euthanasia” victims were transported from the intermediate institutions such as Galkhausen to the killing centers in buses operated by a specially founded ‘Gemeinnützige Kranken-Transport-GmbH’ (charitable hospital transport company)

The “euthanasia” victims were transported from the intermediate institutions such as Galkhausen to the killing centers in buses operated by a specially founded ‘Gemeinnützige Kranken-Transport-GmbH’ (charitable hospital transport company)

Under T4, disabled individuals were transported from hospitals and care facilities to designated killing centers where they were murdered, often using gas chambers — a method later scaled up during the Holocaust. In addition to gassing, patients were killed by lethal injection, starvation, or neglect. Many of the initial T4 killings were carried out in facilities like Hadamar and Hartheim, where doctors and nurses who had pledged to care for the vulnerable became agents of death.

The Cologne “euthanasia” victims were transported via the Galkhausen institution (now Langenfeld) to the Hadamar killing center in the Westerwald.

The Cologne “euthanasia” victims were transported via the Galkhausen institution (now Langenfeld) to the Hadamar killing center in the Westerwald.

An estimated 70,000 disabled people were murdered through T4 by 1941, when public protests led to a nominal suspension of the program. However, the killings continued in secret throughout the war, often under the guise of medical “treatments” or through informal extensions of the T4 policies. By 1945, over 100,000 adults and 20,000 children had been murdered, marking one of the most tragic aspects of Nazi eugenics.

Smoking chimney of the crematorium of the Hadamar killing center, 1941. The killing of people in gas chambers was used for the first time on the ‘euthanasia’ victims.

Smoking chimney of the crematorium of the Hadamar killing center, 1941. The killing of people in gas chambers was used for the first time on the ‘euthanasia’ victims.

Public resistance and limited opposition

While the Nazi regime tightly controlled information about the T4 program, knowledge of the killings did reach the public, and resistance emerged from various segments of society. Religious leaders, including prominent figures like Bishop Clemens August von Galen of Münster, condemned the program in sermons and public statements, calling the murders of disabled individuals an affront to Christian values. His vocal opposition helped fuel public discontent, and the growing awareness of the program’s brutality led some citizens to question the morality of the regime.

As a result of this backlash, the Nazi leadership officially suspended the T4 program in 1941. However, the killings continued in secret, often at a smaller scale, and local authorities were encouraged to act independently in eliminating “unworthy” lives from their jurisdictions. This hidden continuation of T4 policies demonstrates the regime’s unyielding commitment to its eugenics goals, regardless of opposition or public opinion.

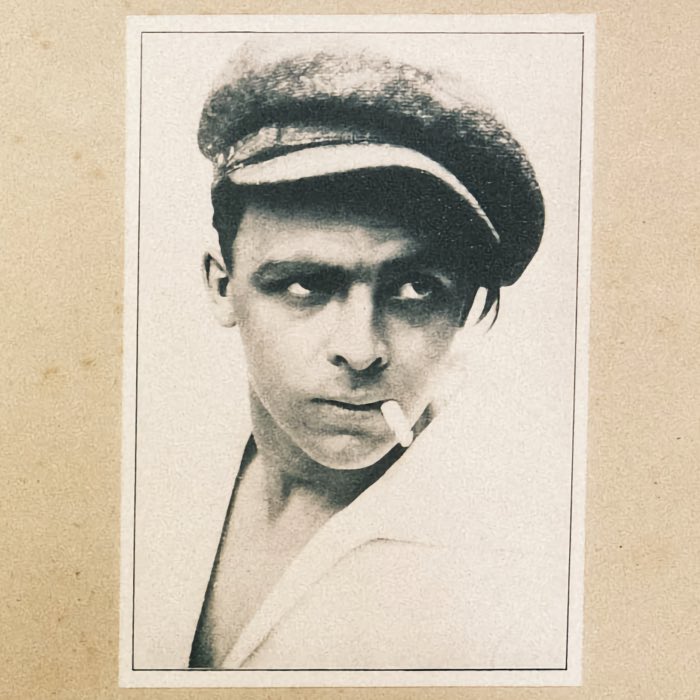

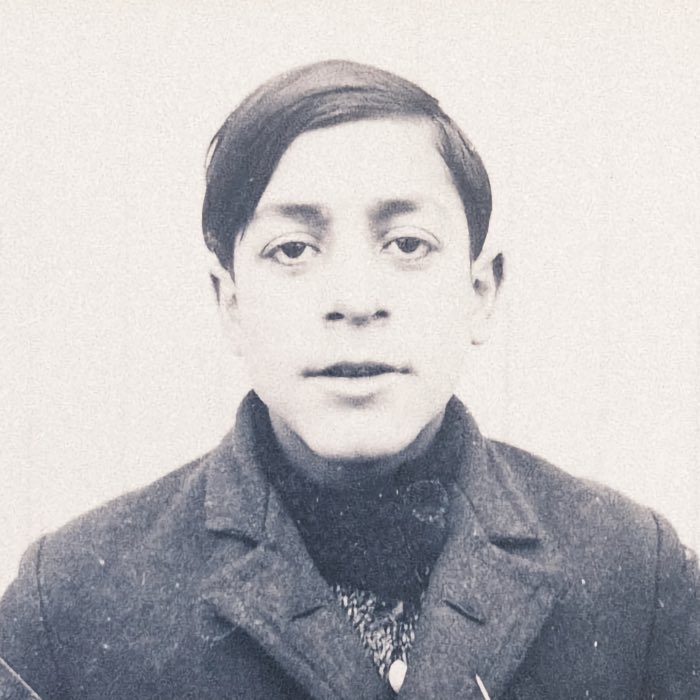

Hitler’s letter that became the basis of the “euthanasia” murders (left) and Friedrich Tillmann (right). Friedrich Tillmann, the director of the Cologne orphanages, worked as an office manager at the “euthanasia” headquarters in Berlin from the summer of 1940 to the fall of 1941 in addition to his work in Cologne. In a letter dated September 1, 1939, Hitler appointed the head of the “Chancellery of the Führer” Bouhler and his accompanying physician Dr. Brandt as “euthanasia” commissioners. Not a law, but this letter alone formed the basis for the “euthanasia” murders.

Hitler’s letter that became the basis of the “euthanasia” murders (left) and Friedrich Tillmann (right). Friedrich Tillmann, the director of the Cologne orphanages, worked as an office manager at the “euthanasia” headquarters in Berlin from the summer of 1940 to the fall of 1941 in addition to his work in Cologne. In a letter dated September 1, 1939, Hitler appointed the head of the “Chancellery of the Führer” Bouhler and his accompanying physician Dr. Brandt as “euthanasia” commissioners. Not a law, but this letter alone formed the basis for the “euthanasia” murders.

The legacy of Nazi persecution of disabled individuals

In the post-war period, the plight of disabled victims of Nazi persecution was often overshadowed by other narratives of the Holocaust. Like other groups labeled as “unworthy” by Nazi ideology, people with disabilities faced societal stigma, and their suffering was not widely recognized. It was not until decades later that a broader acknowledgment of their experiences emerged, with memorials, public discourse, and historical studies helping to bring their stories to light.

Today, the legacy of Nazi policies toward disabled individuals remains a powerful reminder of the dangers inherent in eugenics ideologies and unchecked state power over vulnerable populations. Recognizing the experiences of these forgotten victims is essential to fully understanding the scope of Nazi crimes and to honoring those whose lives were deemed expendable in the pursuit of a distorted ideal.

Conclusion

The Nazi regime’s treatment of disabled individuals, from forced sterilization to systematic murder, reflects the regime’s ruthless pursuit of a “pure” and “healthy” society. By targeting those they deemed “unfit”, the Nazis revealed the extreme consequences of a worldview that valued human life solely based on perceived utility. The legacy of the T4 Euthanasia Program and other atrocities against disabled people underscores the importance of protecting the rights and dignity of all individuals, especially the vulnerable.

Institutions like the El-De Haus play an essential role in preserving the memories of these victims, ensuring that their suffering is neither ignored nor forgotten. By educating future generations on the persecution of disabled individuals under Nazi rule, we reinforce the imperative to stand against ideologies that marginalize and dehumanize. Remembering these victims challenges us to reaffirm the universal right to life, dignity, and respect for all people.

References and further reading

- Website of the NS Documentation Center El-De Hausꜛ

- NS-Dokumentationszentrum der Stadt Köln, Köln im Nationalsozialismus: Ein Kurzführer durch das ELDE Haus (NS-Dokumentation), 2010, Emons Verlag, ISBN: 978-3897052093

- Werner Jung, Bilder einer Stadt im Nationalsozialismus: Köln 1933-1945, 2016, Emons Verlag, ISBN: 9783740800147

- Horst Matzerath, Geschichte der Stadt Köln, Bd. 12: Köln in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus 1933-1945, 2009, Greven, ISBN: 978-3774304291

- Hans Peter Richter, Damals war es Friedrich: Roman, 1979, dtv Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG, ISBN: 978-3423078009.

comments