Christian ivory carvings and their comparison with Japanese netsuke: A cross-cultural analysis

Recently, I had the opportunity to visit an exhibition on netsuke, small, intricate Japanese carvings, traditionally attached to items like medicine boxes (inrō). The exhibition was amazing and you can read a brief report about it here. While strolling through the exhibition, I also noticed a similarity with European Christian ivory carvings. Japanese netsuke and Christian ivory carvings both have their roots in the meticulous art of ivory carving. However, they differ considerably in purpose, symbolism and stylistic expression. Unfortunately, there was no exhibition about the latter that I could have visited at the same time or before. So I searched through my photo archives and put together some examples of European ivory carvings here.

Dancing Death, Germany, c. 1700, ivory. The dancing movement in particular has a long tradition: it is rooted in the popular belief in the Middle Ages that the dead rise from their graves at midnight and perform a dance in the cemetery. From the end of the 14th century, the dance of death was also the motif for the “Black Death”, the plague. The most unusual and shocking aspect of the Dance of Death motif for contemporaries was the combination of the theme of death with dance - one of the most vital expressions of the joy and affirmation of life. This macabre combination of opposites will not have failed to have a moral effect.

Dancing Death, Germany, c. 1700, ivory. The dancing movement in particular has a long tradition: it is rooted in the popular belief in the Middle Ages that the dead rise from their graves at midnight and perform a dance in the cemetery. From the end of the 14th century, the dance of death was also the motif for the “Black Death”, the plague. The most unusual and shocking aspect of the Dance of Death motif for contemporaries was the combination of the theme of death with dance - one of the most vital expressions of the joy and affirmation of life. This macabre combination of opposites will not have failed to have a moral effect.

Christian ivory carvings

Ivory carving flourished as a Christian art form particularly from the 9th to the 11th centuries. It was a rare and expensive material, often imported from Africa and Asia, making it a highly prized commodity. The carvings were deeply rooted in the spiritual and social fabric of medieval Europe. They were not mere decorations but served as symbols of devotion, teaching tools, and embodiments of religious narratives. The themes often depicted scenes from the Bible, the life of Christ, and the saints, and it was commonly used for the following purposes:

- Diptychs and triptychs: Hinged panels that can be opened and closed like a book. They were often used as portable altars or for private devotion. The panels typically featured scenes from the life of Christ or the Virgin Mary.

- Reliquaries: Containers used to house and protect relics of saints. Ivory was chosen for some reliquaries due to its perceived purity and the connection between the white material and spiritual ideals.

- Book covers: Many high-value manuscripts, including Bibles and psalters, had covers adorned with intricate ivory carvings depicting religious scenes or figures.

- Caskets and boxes: Used for storing valuables, these items were often decorated with scenes from courtly love, as well as religious imagery, reflecting the fusion of secular and sacred themes.

The process of carving ivory is exceptionally challenging due to the material’s hardness and the risk of cracking. Medieval craftsmen displayed remarkable skill, creating detailed and delicate works despite these difficulties. They employed a range of techniques, including relief carving, where the figures stand out from the background, and in-the-round carving, where the figure is fully sculpted in three dimensions.

Christian ivory carvings were not only significant in religious and artistic terms but also played a role in the cultural and political landscape of the Middle Ages. They were often exchanged as diplomatic gifts, serving as symbols of wealth and power. Additionally, the spread of these objects across Europe illustrates the interconnectedness of the Christian world during this period.

Examples of Christian ivory carvings

Here are some examples of Christian ivory carvings from my archive that I found during my recent museum visits::

Diptych with the Virgin Mary and the Crucifixion, France or Rhineland, 2nd half of the 14th cent., Ivory. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Diptych with the Virgin Mary and the Crucifixion, France or Rhineland, 2nd half of the 14th cent., Ivory. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Ottonian Reliquary Casket, 1st half of the 11th cent., Ivory (lid), bone (long sides). Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Ottonian Reliquary Casket, 1st half of the 11th cent., Ivory (lid), bone (long sides). Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Christ at the scourging column, Flemish (?), 2nd quarter 17th century, ivory. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Christ at the scourging column, Flemish (?), 2nd quarter 17th century, ivory. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Double-sided bead of a rosary, Southern Netherlands, c. 1520, Ivory with traces of polychromy. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Double-sided bead of a rosary, Southern Netherlands, c. 1520, Ivory with traces of polychromy. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Diptych with the nativity of Jesus, the adoration of the Magi, the Crucifixion and the Last Judgment Cologne (?), c. 1350-1370, Ivory, silver hinges. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Diptych with the nativity of Jesus, the adoration of the Magi, the Crucifixion and the Last Judgment Cologne (?), c. 1350-1370, Ivory, silver hinges. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Book Cover with the Coronation of St. Gereon and St. Victor from St. Gereon in Cologne. Front: Christ as the Ruler of the World with the martyrs St. Gereon and St. Victor and further Saints of the Theban Legion, Cologne, c. 1000. Reverse: Christ between the apostles Peter and Paul (?), Byzantium, 5th-6th cent., book cover: 7th-12th cent. (?), Ivory, book cover: oak, copper, originally gilded, filigree, original decoration with polished stones and presumably enamel plaques. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Book Cover with the Coronation of St. Gereon and St. Victor from St. Gereon in Cologne. Front: Christ as the Ruler of the World with the martyrs St. Gereon and St. Victor and further Saints of the Theban Legion, Cologne, c. 1000. Reverse: Christ between the apostles Peter and Paul (?), Byzantium, 5th-6th cent., book cover: 7th-12th cent. (?), Ivory, book cover: oak, copper, originally gilded, filigree, original decoration with polished stones and presumably enamel plaques. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Rosary with so-called Wendehäupter, South Netherlands and France (?), end of the 15th-middle of the 17th cent., ivory, gilded silver, knobbed pearls soldered with filigree. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Rosary with so-called Wendehäupter, South Netherlands and France (?), end of the 15th-middle of the 17th cent., ivory, gilded silver, knobbed pearls soldered with filigree. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Rosary with so-called Wendehäupter, South Netherlands and France (?), end of the 15th-middle of the 17th cent., ivory, gilded silver, knobbed pearls soldered with filigree. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Rosary with so-called Wendehäupter, South Netherlands and France (?), end of the 15th-middle of the 17th cent., ivory, gilded silver, knobbed pearls soldered with filigree. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Memento Mori, two-sided ivory sculpture. Bode Museum, Berlin. Bode Museum, Berlin. See more from this exhibition here.

Memento Mori, two-sided ivory sculpture. Bode Museum, Berlin. Bode Museum, Berlin. See more from this exhibition here.

Southern Italy (Amalfi), queen (chess piece), ca. 1100, ivory. Bode Museum, Berlin. Bode Museum, Berlin. See more from this exhibition here.

Southern Italy (Amalfi), queen (chess piece), ca. 1100, ivory. Bode Museum, Berlin. Bode Museum, Berlin. See more from this exhibition here.

Southern Italy (Amalfi). Crucifixion, below the Ecclesia is received and the synagogue is rejected, ca. 1075-1100, ivory. Bode Museum, Berlin. Bode Museum, Berlin. See more from this exhibition here.

Southern Italy (Amalfi). Crucifixion, below the Ecclesia is received and the synagogue is rejected, ca. 1075-1100, ivory. Bode Museum, Berlin. Bode Museum, Berlin. See more from this exhibition here.

Pyxis with Christ between the apostles and Abraham’s sacrifice, place of manufacture unknown, around 400, ivory. Bode Museum, Berlin. See more from this exhibition here.

Pyxis with Christ between the apostles and Abraham’s sacrifice, place of manufacture unknown, around 400, ivory. Bode Museum, Berlin. See more from this exhibition here.

Capsule with relief plague, Athos, 16th cent., ivory. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Capsule with relief plague, Athos, 16th cent., ivory. Museum Schnütgen, Cologne.

Anonymous, Resurrection of Christ, South Germany, 1st quarter of the 17th century. Ivory, triple frame, bronze fire-gilded. Bode Museum, Berlin. See more from this exhibition here.

Anonymous, Resurrection of Christ, South Germany, 1st quarter of the 17th century. Ivory, triple frame, bronze fire-gilded. Bode Museum, Berlin. See more from this exhibition here.

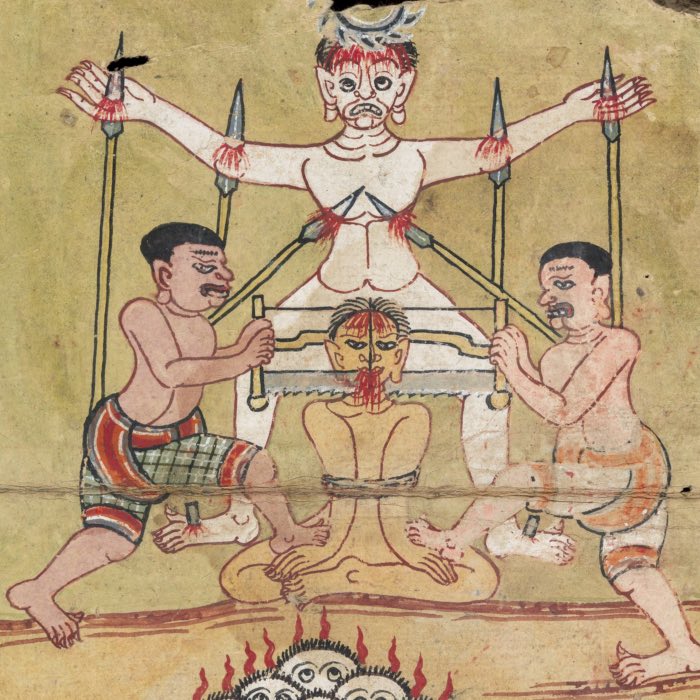

Naples, 1st half 18th c. Fall of the apostate angels and The Last Judgment, ivory, wood, gilded copper sheet, part of an altar decoration. Bode Museum, Berlin. See more from this exhibition here.

Naples, 1st half 18th c. Fall of the apostate angels and The Last Judgment, ivory, wood, gilded copper sheet, part of an altar decoration. Bode Museum, Berlin. See more from this exhibition here.

Left: Furienmeister, active in the 17th century, dragon fighting group, c. 1620, ivory, bone, wood. Right: Furienmeister, active in the 17th century, Mars, Venus and Cupid (?), around 1620, ivory, bone, wood. Bode Museum, Berlin. See more from this exhibition here.

Left: Furienmeister, active in the 17th century, dragon fighting group, c. 1620, ivory, bone, wood. Right: Furienmeister, active in the 17th century, Mars, Venus and Cupid (?), around 1620, ivory, bone, wood. Bode Museum, Berlin. See more from this exhibition here.

Examples of Japanese netsuke

And here are again some examples of Japanese netsuke from the exhibition that I visited recently:

Sumō-wrestler. Ivory and black horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Sumō-wrestler. Ivory and black horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Kinko Sennin riding a carp. Ivory and black horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Kinko Sennin riding a carp. Ivory and black horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Pair of monkeys. Ivory, 18th century (Edo period), Japan. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Pair of monkeys. Ivory, 18th century (Edo period), Japan. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Rat clutching a chilli pepper. Ivory and black horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Rat clutching a chilli pepper. Ivory and black horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Ivory and black horn, 18th century (Edo period). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Ivory and black horn, 18th century (Edo period). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Ivory, light, and dark horn (left) and reddish horn (right), 18h century (Edo period). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Ivory, light, and dark horn (left) and reddish horn (right), 18h century (Edo period). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Ivory, light, and dark horn, 19th century (Edo period). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Ivory, light, and dark horn, 19th century (Edo period). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Ivory and dark horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Ivory and dark horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan. Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Howling deer, ivory and dark horn, 18th/19th century (Edo period). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Howling deer, ivory and dark horn, 18th/19th century (Edo period). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Contortionist, ivory, 18th century (Edo period). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Contortionist, ivory, 18th century (Edo period). Museum for East Asian Art, Cologne. See more about this exhibition here.

Comparison

While both European Christian ivory carvings and Japanese netsuke are rooted in the meticulous art of ivory sculpting, they diverge significantly in purpose, symbolism, and stylistic expression:

Function and use

One of the most striking differences lies in their functional use. Medieval Christian ivory pieces were primarily religious in nature, intended for worship, moral instruction, or as part of religious rituals. In contrast, netsuke had a more utilitarian purpose in Edo-period Japan (17th-19th century), serving as toggles to secure small personal items like pouches or cases to a kimono sash, as the traditional Japanese garment lacked pockets.

Symbolism and themes

The themes and symbolism of the two art forms also reflect their distinct cultural contexts. Christian ivories are imbued with religious iconography, depicting scenes from the Bible and the lives of saints, intended to inspire piety and devotion. Netsuke, however, often portrays everyday life, folklore, mythology, and even humorous or erotic subjects, reflecting the secular and societal aspects of Japanese culture.

Artistic style and techniques

In terms of artistic style, European ivory carvings of the Middle Ages often display a preference for high relief and intricate detailing, aligned with the Gothic and Romanesque artistic sensibilities of the time. Netsuke, on the other hand, is characterized by its compact, three-dimensional form, designed to be tactile as well as visually appealing. The craftsmanship of netsuke is also notable for its variety and the playful creativity it often exhibits.

Cultural significance

Both art forms hold significant cultural value in their respective societies. Christian ivory carvings were not only religious artifacts but also symbols of wealth and power in medieval Europe. Netsuke, while utilitarian, became highly prized as art objects, reflecting the wearer’s personal taste and social status in feudal Japanese society of the time.

Preservation and legacy

Today, both Christian ivory carvings and netsuke are celebrated for their historical and artistic value. They continue to be subjects of fascination, offering insights into the religious, social, and cultural fabric of their respective periods and regions.

Conclusion

The comparison between Christian ivory carvings of the Middle Ages and Japanese netsuke reveals more than just the technical prowess involved in ivory carving. It opens a window into understanding how different cultures can imbue a similar medium with vastly different meanings and purposes. These art forms, each deeply rooted in their respective cultural and historical contexts, offer a rich tapestry of human expression and creativity. As we appreciate their beauty and intricacy, we also gain a deeper appreciation for the diverse ways in which art narrates the human experience.

References and further reading

- Rosemary Bandini, Kyotos Netsuke: Meister & Mythen, 2023, ISBN: 9783981266689

- Uta Werlich, & Susanne Germann, Inrō: Japanese Belt Ornaments: the Trumpf Collection, 2016, Arnold’sche, ISBN: 9783897904446

- Noriko Tsuchiya, Netsuke: 100 Miniature Masterpieces from Japan, 2014, ISBN: 9780714124810

- Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss, Schrecklich schön. Elefant - Mensch - Elfenbein, 2021, ISBN: 9783777433622

- Eike D. Schmidt, Das Elfenbein der Medici: Bildhauerarbeiten für den Florentiner Hof von Giovanni Antonio Gualterio, dem Furienmeister, Leonhard Kern, Johann Balthasar Stockamer, Melchior Barthel, Lorenz Rues, Francis van Bossuit, Balthasar Griessmann und Balthasar Permoser, 2012, Hirmer Verlag GmbH, ISBN: 9783777456416

comments