Netsuke – The elegance of Japanese craftsmanship

I recently strolled through the Museum of East Asian Art again. This time, the museum is celebrating the 60-year partnership between Cologne and Kyōto with the exhibition “Kyōto’s Netsuke - Masters & Mythsꜛ”. The exhibition showcases an extraordinary selection of netsuke from the Kyōto school, each piece, a small but significant carving, embodying the exceptional Japanese craftsmanship and echoing a long-standing friendship between the two cities.

Netsuke are small and intricately carved figures, traditionally made of materials like ivory, wood, or bone. This netsuke shows a tigress licking her cub, made of ivory, from 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Netsuke are small and intricately carved figures, traditionally made of materials like ivory, wood, or bone. This netsuke shows a tigress licking her cub, made of ivory, from 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

“Kyōto’s Netsuke - Masters & Mythsꜛ”, currently running at the Museum of East Asian Art in Cologne from November 30, 2023, to April 1, 2024.

“Kyōto’s Netsuke - Masters & Mythsꜛ”, currently running at the Museum of East Asian Art in Cologne from November 30, 2023, to April 1, 2024.

Kyoto’s netsuke

Netsuke, small and intricately carved figures, traditionally made of materials like ivory, wood, or bone, trace their origins back to Japan’s Edo period (1603-1868). Initially designed to attach small containers like inrō (lit. “seal container”, mostly used as a medicine box) and sagemono (lit. “hanging things”) to a person’s obi (see image below), these pieces not only served functional purposes, but also became a form of aesthetic expression, blending art and utility in a unique fashion.

Sketch showing the use of netsuke to attach sagemono (lit. “hanging things”) to a person’s obi. Sagemono can be small containers like inrō (lit. “seal container”), tabakoire (tobacco container), tonkotsu (container for leftovers), or dōran (case).

Sketch showing the use of netsuke to attach sagemono (lit. “hanging things”) to a person’s obi. Sagemono can be small containers like inrō (lit. “seal container”), tabakoire (tobacco container), tonkotsu (container for leftovers), or dōran (case).

Examples of three different inrō.

Examples of three different inrō.

Kyōto, even after Edo (present-day Tōkyō) became Japan’s political capital in 1603, continued to flourish as a cultural and artistic hub. The city’s artisans, influenced by painting schools like those of Maruyama Okyoꜛ and Ogata Kōrinꜛ, frequently depicted animals and mythical creatures. This artistic inclination can be attributed to the schools’ revolutionary approaches to realism and material treatment.

Painting by Kameoka Kirei (1770-1835). From: Paintings by 27 Pupils of Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795). Handscroll, ink and light color on paper between 1789 and 1801. The handscroll comprises 48 sketches of figures, land-scapes, plants and animals rendered by pupils and successors of Maruyama Okyo. The Maruyama-Shijo school, a significant force in Japanese art during the Edo and Meiji periods, was renowned for its distinctive style. This school skillfully blended traditional Japanese artistic techniques with Western elements of naturalism and realism, creating a unique and influential aesthetic.

Painting by Kameoka Kirei (1770-1835). From: Paintings by 27 Pupils of Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795). Handscroll, ink and light color on paper between 1789 and 1801. The handscroll comprises 48 sketches of figures, land-scapes, plants and animals rendered by pupils and successors of Maruyama Okyo. The Maruyama-Shijo school, a significant force in Japanese art during the Edo and Meiji periods, was renowned for its distinctive style. This school skillfully blended traditional Japanese artistic techniques with Western elements of naturalism and realism, creating a unique and influential aesthetic.

The geographical position of Kyōto, linking it to southern Japan’s economic powerhouses like Osaka and Nagasaki, played a pivotal role in its cultural development. During Japan’s isolationist Edo period, Nagasaki became a crucial point for trade, particularly for the importation of precious elephant ivory by the Dutch East India Company. This scarce resource was diligently utilized by Kyōto craftsmen, who transformed it into exquisite artworks in specialized workshops.

Seascape, showing a Dutch ship and a steamship. Woodblock (ukiyo-e) print, Nagasaki-e, unknown artist, 19th century, Nagasaki, Japan. Source: The British Museum (license: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Seascape, showing a Dutch ship and a steamship. Woodblock (ukiyo-e) print, Nagasaki-e, unknown artist, 19th century, Nagasaki, Japan. Source: The British Museum (license: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The distinct characteristics of Kyōto’s netsuke stem from the conscientious use of the material. Craftsmen skillfully adapted their designs to the available material, often incorporating the natural grain and texture of the ivory or wood to enhance realism. Even damaged or cracked material was used creatively.

Rat clutching a chilli pepper. Ivory and black horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Rat clutching a chilli pepper. Ivory and black horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Dragon emerging from an alms bowl. Ivory, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Dragon emerging from an alms bowl. Ivory, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Dog with a kemari ball (left), Dog with a collar (middle), and Mountain dog with a crab (right). Ivory, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Dog with a kemari ball (left), Dog with a collar (middle), and Mountain dog with a crab (right). Ivory, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Rolling horse. Ivory and black horn, 19th century (Edo period), Japan.

Rolling horse. Ivory and black horn, 19th century (Edo period), Japan.

Pair of monkeys. Ivory, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Pair of monkeys. Ivory, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Roaring shishi with a loose ball in its mouth (left), shishi and cub (middle), and roaring shishi with a loose ball in its mouth (right). Ivory and black horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Roaring shishi with a loose ball in its mouth (left), shishi and cub (middle), and roaring shishi with a loose ball in its mouth (right). Ivory and black horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Sumō-wrestler. Ivory and black horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Sumō-wrestler. Ivory and black horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Portrait of two sumō-wrestlers, with poems on the left. Woodblock Print (ukiyo-e), 1830ies, Japan.

Portrait of two sumō-wrestlers, with poems on the left. Woodblock Print (ukiyo-e), 1830ies, Japan.

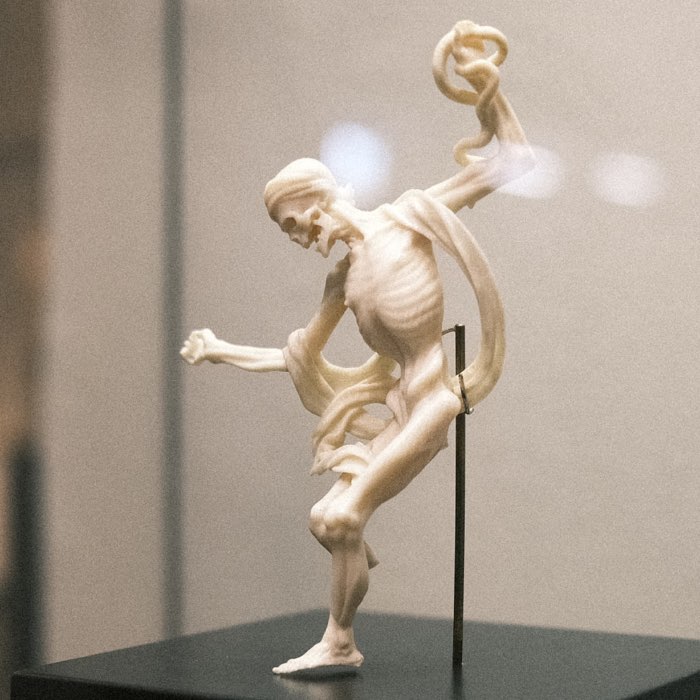

The Big Three of Kyōto Netsuke: Tomotada (top: Reclining ox, Ivory and horn, 18th century), Masanao (center: Sleeping rat, Ivory, 18th century), and Yoshinaga (bottom: Contortionist, Ivory, 18th century) are considered Kyōto’s most important netsuke carvers.

The Big Three of Kyōto Netsuke: Tomotada (top: Reclining ox, Ivory and horn, 18th century), Masanao (center: Sleeping rat, Ivory, 18th century), and Yoshinaga (bottom: Contortionist, Ivory, 18th century) are considered Kyōto’s most important netsuke carvers.

Kinko Sennin riding a carp. Ivory and black horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Kinko Sennin riding a carp. Ivory and black horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Left: Hibiscus by Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795). Hanging scroll (kakemono), color on silk, dated 1772, Japan. Right: Carp by Itō Jakuchu (1716-1800, right). Hanging scroll (kakemono), ink on paper, late 18th century, Japan. According to a Chinese legend, a carp turned into a dragon after it had overcome a waterfall.

Left: Hibiscus by Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795). Hanging scroll (kakemono), color on silk, dated 1772, Japan. Right: Carp by Itō Jakuchu (1716-1800, right). Hanging scroll (kakemono), ink on paper, late 18th century, Japan. According to a Chinese legend, a carp turned into a dragon after it had overcome a waterfall.

Puppy with an abalone (awabi). Ivory and dark horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Puppy with an abalone (awabi). Ivory and dark horn, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Parallels to European art

During my visit, I noticed an interesting parallel between the Japanese ivory carvings and Christian ivory pendants and brooches from the medieval and Renaissance periods. Despite their differing origins, both art forms display a deep respect for intricate craftsmanship. The netsuke’s detailed animal and mythical motifs parallel the religious and heraldic symbols in European ivory art, reflecting a universal admiration for artistic skill. In my opinion, this unexpected connection across continents and cultures again highlights the universal human appreciation for beauty and skill, and how the same materials can inspire such diverse and profound artistic expressions.

Howling kirin (a mythical creature; it is also known as the “Chinese unicorn”. Alongside the dragon, the phoenix, and the tortoise, the kirin is one of the “four wonder animals”, which are also known as magical creatures.). Ivory, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

Howling kirin (a mythical creature; it is also known as the “Chinese unicorn”. Alongside the dragon, the phoenix, and the tortoise, the kirin is one of the “four wonder animals”, which are also known as magical creatures.). Ivory, 18th century (Edo period), Japan.

One side of a double-sided bead of a rosary, Southern Netherlands, c. 1520, ivory with traces of polychromy. I took this image at the Museum Schnütgen in August this year.

One side of a double-sided bead of a rosary, Southern Netherlands, c. 1520, ivory with traces of polychromy. I took this image at the Museum Schnütgen in August this year.

Ivory – A moral dilemma

Walking through the exhibition, I felt a deep respect for the artistic skill these pieces represent. However, the use of ivory couldn’t escape my notice. In today’s world, where we are increasingly aware of the importance of wildlife conservation, the use of ivory for sure poses a moral dilemma. It’s a relief to know that our today’s sensibilities prioritize animal welfare over artistic medium, even if the shadows of the past still linger. Regrettably, despite this shift in ethics, the illegal trade of ivory for netsuke still seems to persistꜛ, as a quick search after my visit revealed. My hope is that growing awareness will extend to both creators and collectors, leading to a decisive end to the global demand for ivory, thus honoring both art and the sanctity of wildlife.

Conclusion

As I reflect on my experience at the “Kyōto’s Netsuke - Masters & Myths” exhibition, I am left with a profound sense of admiration for the artistry and history embodied in each netsuke. These tiny sculptures are not merely artifacts; they are storytellers of a rich cultural heritage, bridging the past and present. The parallels drawn between these netsuke and European ivory carvings reinforce the universal language of art, transcending cultural and temporal boundaries.

However, this admiration is also tempered by a contemporary understanding of ethical responsibility, especially regarding the use of ivory. The lingering beauty of these pieces reminds us of the delicate balance between preserving artistic heritage and promoting responsible, sustainable practices. In my opinion, this exhibition, therefore, serves not just as a celebration of craftsmanship and the 60-year partnership between Cologne and Kyōto, but also as a catalyst for important conversations about the future of art and conservation. As we move forward, embracing both our cultural legacies and our commitment to ethical stewardship, exhibitions like this play a vital role in shaping our understanding of art’s role in society and the environment.

Of course, these reflections are purely my personal impressions. I highly encourage you to visit the exhibition and form your own experiences. It will be open until April 1, 2024ꜛ. Independently of this particular exhibition, the Museum of East Asian Art is a destination in its own right, boasting an excellent permanent exhibition that’s well worth a visit anyways.

The stone garden at the Museum.

The stone garden at the Museum.

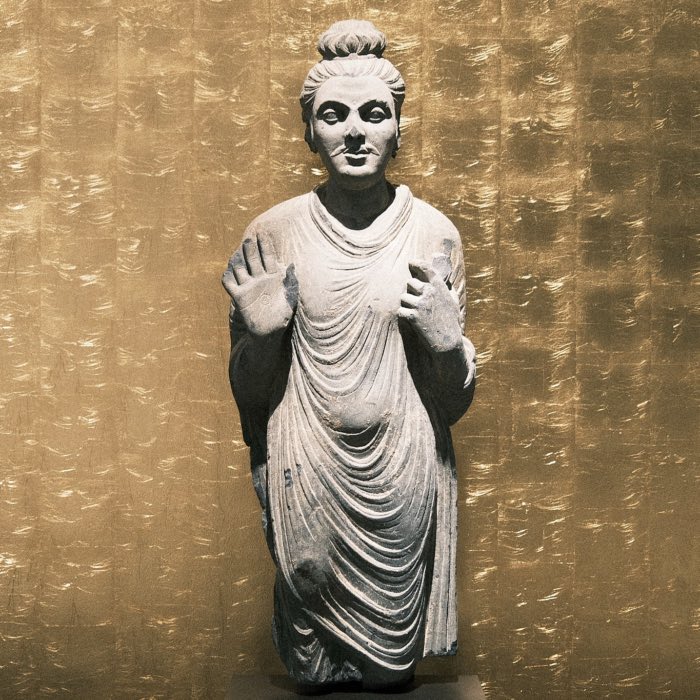

The favorite disciples of the Buddha: Young Ananda and old Kashyapa count among the closest followers of the historical Buddha. They represent the monastic virtues. Bronze, cast, gilt, China, Ming dynasty, Chongzhen period (1628-44).

The favorite disciples of the Buddha: Young Ananda and old Kashyapa count among the closest followers of the historical Buddha. They represent the monastic virtues. Bronze, cast, gilt, China, Ming dynasty, Chongzhen period (1628-44).

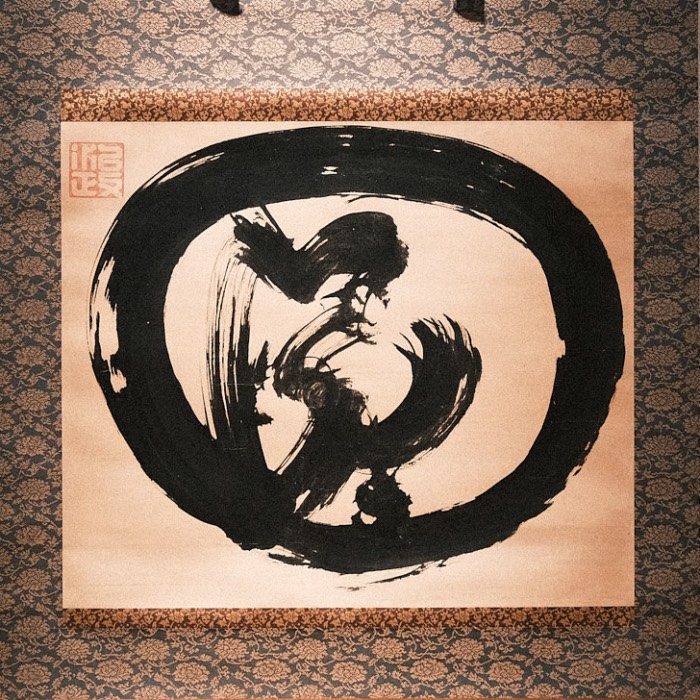

From left to right: kō, the Confucian virtue of filial piety, tenjō, what is above heaven (relates to the sphere of religion), and myō, mystery or secret. Calligraphy by Inoue Yūichi (1916-1985). Ink on paper, Japan, beginning of 1960s.

From left to right: kō, the Confucian virtue of filial piety, tenjō, what is above heaven (relates to the sphere of religion), and myō, mystery or secret. Calligraphy by Inoue Yūichi (1916-1985). Ink on paper, Japan, beginning of 1960s.

Plum blossom by Inoue Yūichi (1916-1985). Ink on paper, Japan, 1966. Along with bamboo and pine tree, the plum blossom is regarded as one of the ‘friends of winter’ and stands for purity, virtue and life energy. The blossoms, flurrying through the air (as Yūichi’s calligraphy reflects exactly this motion), are a metaphor for transience and death, characterizing disintegration and decay.

Plum blossom by Inoue Yūichi (1916-1985). Ink on paper, Japan, 1966. Along with bamboo and pine tree, the plum blossom is regarded as one of the ‘friends of winter’ and stands for purity, virtue and life energy. The blossoms, flurrying through the air (as Yūichi’s calligraphy reflects exactly this motion), are a metaphor for transience and death, characterizing disintegration and decay.

Top, from left to right: Aizen myōō (hanging scroll (kakemono), ink, colours, gold on silk, Japan, late Kamakura period, 13th- early 14th century), Fudō myōō (hanging scroll (kakemono), ink, colours, gold on silk, registered ‘Important Cultural Property’ (jūyō bunkazai), Japan, Nanbokucho period, late 14th century), and Amida-Buddha (mineral paint and gold on silk, Japan, late Muromachi period, early 16th century). Bottom: Close-up of Aizen myōō. Close-ups of the other pictures can be seen here.

Top, from left to right: Aizen myōō (hanging scroll (kakemono), ink, colours, gold on silk, Japan, late Kamakura period, 13th- early 14th century), Fudō myōō (hanging scroll (kakemono), ink, colours, gold on silk, registered ‘Important Cultural Property’ (jūyō bunkazai), Japan, Nanbokucho period, late 14th century), and Amida-Buddha (mineral paint and gold on silk, Japan, late Muromachi period, early 16th century). Bottom: Close-up of Aizen myōō. Close-ups of the other pictures can be seen here.

References and further reading

- Rosemary Bandini, Kyotos Netsuke: Meister & Mythen, 2023, ISBN: 9783981266689 (this is the exhibition catalog)

- Uta Werlich, & Susanne Germann, Inrō: Japanese Belt Ornaments: the Trumpf Collection, 2016, Arnold’sche, ISBN: 9783897904446

- Noriko Tsuchiya, Netsuke: 100 Miniature Masterpieces from Japan, 2014, ISBN: 9780714124810

- Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss, Schrecklich schön. Elefant - Mensch - Elfenbein, 2021, ISBN: 9783777433622

- Eike D. Schmidt, Das Elfenbein der Medici: Bildhauerarbeiten für den Florentiner Hof von Giovanni Antonio Gualterio, dem Furienmeister, Leonhard Kern, Johann Balthasar Stockamer, Melchior Barthel, Lorenz Rues, Francis van Bossuit, Balthasar Griessmann und Balthasar Permoser, 2012, Hirmer Verlag GmbH, ISBN: 9783777456416

“Kyōto’s Netsuke” exhibition catalogue: Rosemary Bandini, Kyotos Netsuke: Meister & Mythen, 2023, Book, ISBN: 9783981266689.

“Kyōto’s Netsuke” exhibition catalogue: Rosemary Bandini, Kyotos Netsuke: Meister & Mythen, 2023, Book, ISBN: 9783981266689.

comments