The three perfections: Chinese artistic tradition

In the rich Chinese cultural history, three art forms stand out as pillars of classical education and self-expression: poetry, calligraphy, and painting. Collectively, they are known as “The Three Perfections”, representing the culmination of Chinese artistic tradition.

Calligraphy, the art of handwriting, holds a special place in this trinity. While the Chinese script traces its origins back thousands of years, it’s in calligraphy that the script takes on a life of its own. More than just writing, calligraphy is seen as an intimate reflection of a person’s soul, revealing both their personality and virtue. In China, it is elevated to the status of the supreme visual art, a testament to its deep cultural and aesthetic significance.

Despite the ancient and standardized nature of the Chinese writing system, calligraphy is anything but rigid. It offers an expansive canvas for artistic variation and abstraction, allowing the writer’s spirit to flow freely through ink and brush. This fluidity and freedom form the bedrock for paintings by scholar-artists. These paintings, often inscribed with calligraphy, embrace an amateurish quality, underscoring the idea that the act of creation and expression takes precedence over formal representation.

The “Three Perfections” are not limited to scholars and artists. Emperors throughout Chinese history have also dabbled in these arts. However, their motivations were twofold. On one hand, mastering these forms served as a means of legitimizing their power, demonstrating both cultural refinement and divine mandate. On the other, it provided them a path to self-cultivation, allowing introspection, reflection, and growth.

I think, “The Three Perfections” of poetry, calligraphy, and painting offer a profound glimpse into the Chinese psyche. They embody the nation’s deep-rooted reverence for tradition, expression, and personal growth.

“Landscapes” by Hongren

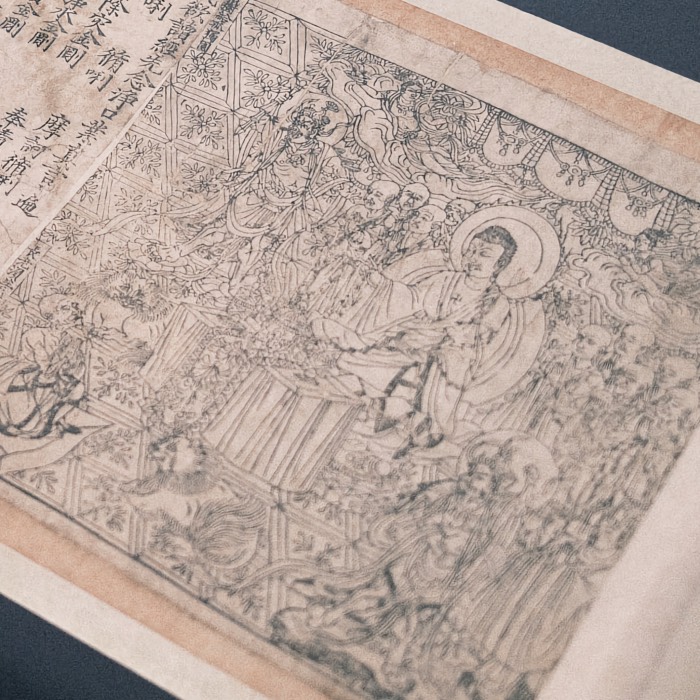

As an example of the “Three Perfections”, I’d like to share a painting series by Hongren, seen at the Humboldt Museum in Berlin. Hongren (chin.: 明 弘仁山水圖册; 1610 - 1663) was a 17th-century Buddhist monk and artist. The painting series “Landscapes” (album with 12 leaves, ink and colors on paper, completed 1656) is based on twelve “fishermen’s poems” depicting the classical literary motif of the fisherman-settler. They were written by Hongren’s close friend Xu Chu (1605-1676) and written directly on the paintings. Opposite are colophons written by Huizhou locals. Their praises for Hongren’s art and character attest to the regionalism of Huizhou literary culture.

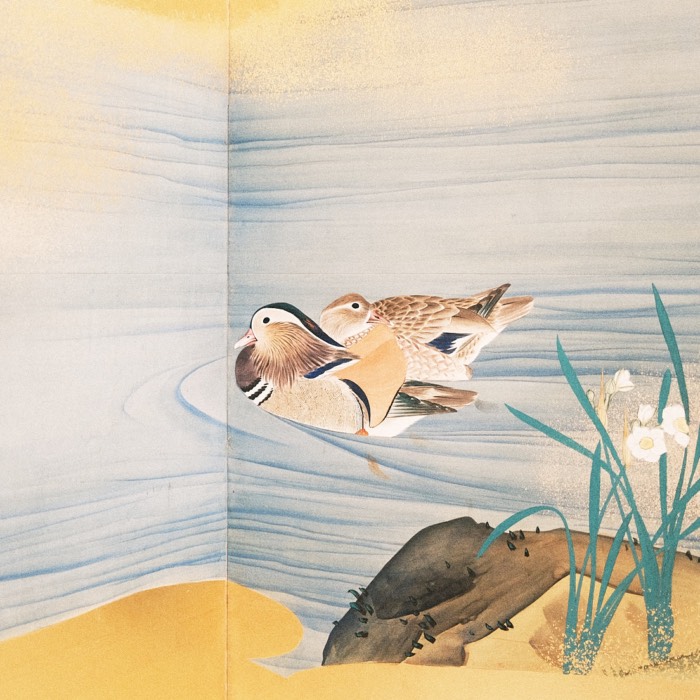

Examples from Japan

Here are some examples of Japanese Zen paintings.

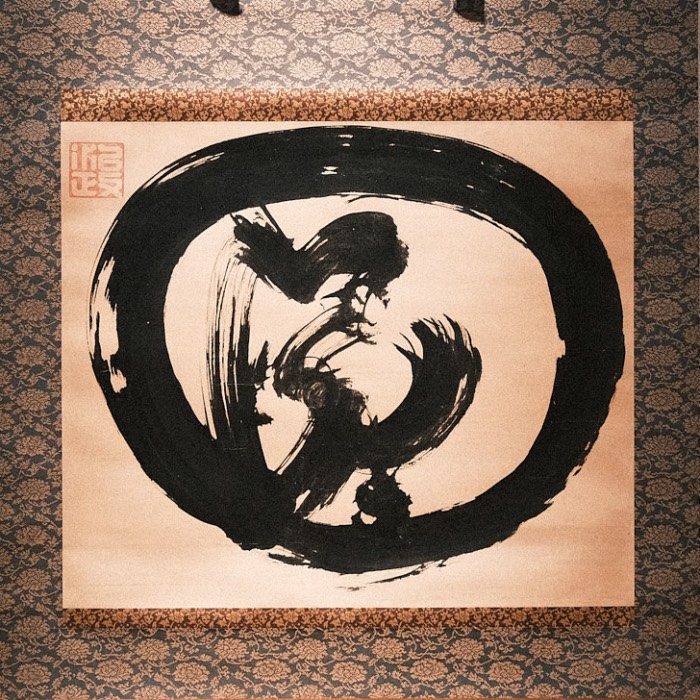

Zen Circle (ensō and the character yume (dream)) by Deiryu (Kanshū Sojun, 1895 -1954), Japan, Showa period, c. 1925 - 1954, hanging scroll, ink on paper.

Zen Circle (ensō and the character yume (dream)) by Deiryu (Kanshū Sojun, 1895 -1954), Japan, Showa period, c. 1925 - 1954, hanging scroll, ink on paper.

Hotei pointing at the moon by Awakawa Yasuichi (1902-1976), Japan, Showa period, 20th c., hanging scroll, ink on paper.

Hotei pointing at the moon by Awakawa Yasuichi (1902-1976), Japan, Showa period, 20th c., hanging scroll, ink on paper.

Blind people crossing an abyss, Japan, Edo period, 18th c., hanging scroll, ink on paper. Inscription: “Inner life and the floating world are like the blind men’s round log bridge – an enlightened mind is the best guide”” (Translated by Stephen Addiss).

Blind people crossing an abyss, Japan, Edo period, 18th c., hanging scroll, ink on paper. Inscription: “Inner life and the floating world are like the blind men’s round log bridge – an enlightened mind is the best guide”” (Translated by Stephen Addiss).

comments