The many faces of the Buddha

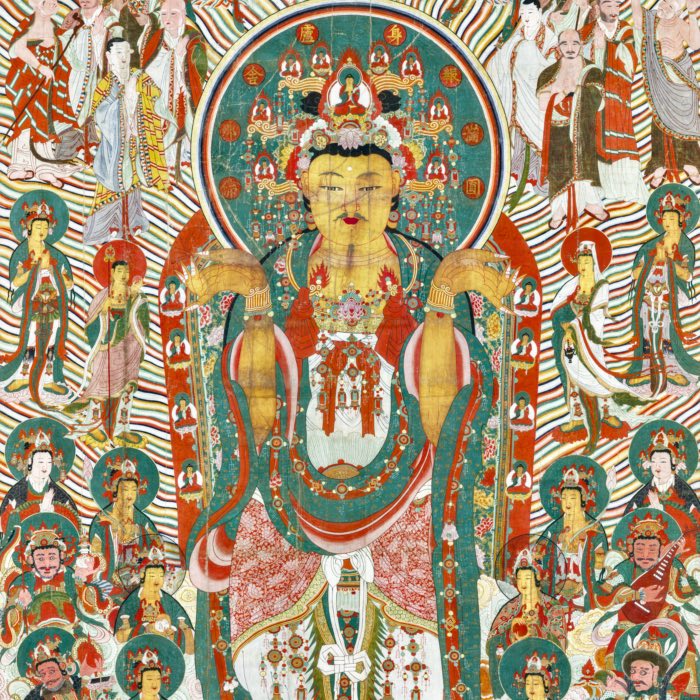

The Humboldt Forum in Berlin holds an extensive collection sculptures of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and Dharma protectors from all over Southeast Asia: China, Japan, Thailand, Cambodia, Tibet, and Nepal. Unfortunately, Korea and Taiwan were a bit underrepresented. In this post, I’d like to show the many faces of Buddhist sculptures that I have discovered in the Forum. The following images show the sculptures, with the accompanying text from the Humboldt Forum.

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in Water Moon form (Chin. 水月觀音菩薩像, Shuiyue Guanyin), China, Song dynasty (960 - 1279), wood. One representation of Avalokiteshvara shows the bodhisattva seated with the right knee raised and the left leg crossed before the body. This posture represents the Water Moon manifestation, understood as a depiction of the bodhisattva in his personal paradise. Also known as Mount Potalaka, this place was originally thought to be located on an island somewhere south of India. In paintings, this bodhisattva is often shown seated on a rocky ledge above water and below a full moon.

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in Water Moon form (Chin. 水月觀音菩薩像, Shuiyue Guanyin), China, Song dynasty (960 - 1279), wood. One representation of Avalokiteshvara shows the bodhisattva seated with the right knee raised and the left leg crossed before the body. This posture represents the Water Moon manifestation, understood as a depiction of the bodhisattva in his personal paradise. Also known as Mount Potalaka, this place was originally thought to be located on an island somewhere south of India. In paintings, this bodhisattva is often shown seated on a rocky ledge above water and below a full moon.

Top left and bottom: 菩薩立像 Standing Bosatsu (Bodhisattva), Japan, Heian period, 10th - 12th c., Wood. Top right: Right: Daiseishi (大勢至) Bosatsu, Edo (Tokugawa) period, 18th century, wood with gold lacquer, Japan. In Sanskrit Mahāsthāmaprāpta (“He who has Attained Great Power”). A bodhisattva best known as one of the two attendants (along with the far more popular Avalokiteśvara) of the Buddha Amitābha. Mahāsthāmaprāpta is said to represent Amitābha’s wisdom, while Avalokiteśvara represents his compassion.

Top left and bottom: 菩薩立像 Standing Bosatsu (Bodhisattva), Japan, Heian period, 10th - 12th c., Wood. Top right: Right: Daiseishi (大勢至) Bosatsu, Edo (Tokugawa) period, 18th century, wood with gold lacquer, Japan. In Sanskrit Mahāsthāmaprāpta (“He who has Attained Great Power”). A bodhisattva best known as one of the two attendants (along with the far more popular Avalokiteśvara) of the Buddha Amitābha. Mahāsthāmaprāpta is said to represent Amitābha’s wisdom, while Avalokiteśvara represents his compassion.

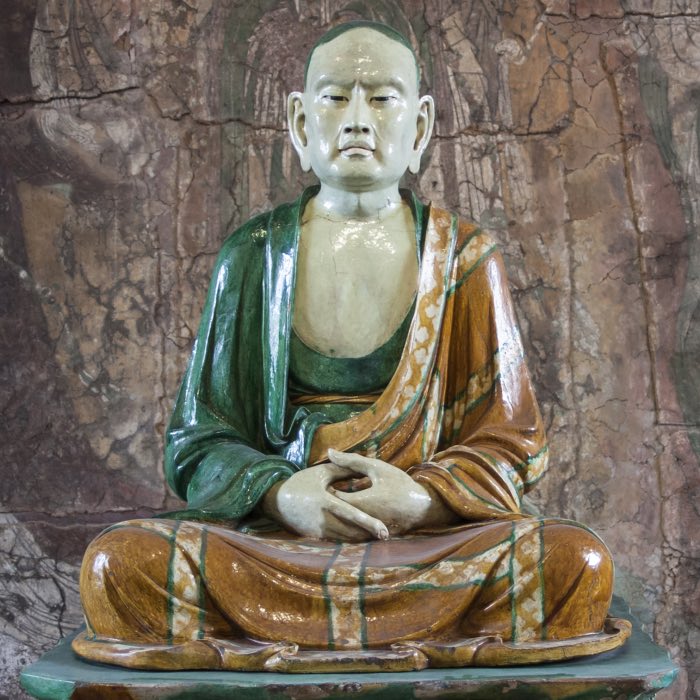

Seated Luohan (chin.: 羅漢坐像, Sanskrit: Arhat), China, Ming dynasty (1368 - 1644), 16th c., clay and coloured glaze.

Seated Luohan (chin.: 羅漢坐像, Sanskrit: Arhat), China, Ming dynasty (1368 - 1644), 16th c., clay and coloured glaze.

Votive stele with 93 Buddhas (chin.: 九十三佛石刻造像碑), North China, Tang dynasty (618-907), 10th c., limestone.

Votive stele with 93 Buddhas (chin.: 九十三佛石刻造像碑), North China, Tang dynasty (618-907), 10th c., limestone.

Guanyin (chin.: 觀音菩薩, Sanskrit: Avalokiteshvara), China, Sui dynasty (581 - 618), 6th c., limestone with remains of colouring and gilding.

Guanyin (chin.: 觀音菩薩, Sanskrit: Avalokiteshvara), China, Sui dynasty (581 - 618), 6th c., limestone with remains of colouring and gilding.

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara with one thousand hands (Chin. Qianshou Qianyan Guanyin), China, Liao dynasty (907-1125), gilt bronze.

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara with one thousand hands (Chin. Qianshou Qianyan Guanyin), China, Liao dynasty (907-1125), gilt bronze.

Mahamayuri Vidyarajni, Imperial workshop, Beijing, China, Inscription dating to the Ming Xuande period (1426-35), fire-gilt bronze with peacock feathers. The object originates from a region that was partly under the influence of colonial powers from 1842 onwards. Should the object have been put on the market after 1842, the possibility of unlawful acquisition cannot be ruled out.

Ushnishavijaya, Imperial workshop, Beijing, China, mid-18th c., gilt bronze with polychromy. Ushnishavijaya is the embodiment of a Buddhist mantra for protection that is supposed to extend life and bring about rebirth in Buddha Amitabha’s “Western Pure Land” Protective mantras consist of sacred syllables that encapsulate the spirit of Buddhist teaching. During a consecration ceremony the bronze was filled with relics such as written documents, medicinal herbs, or the remains of a teacher. These gave it the power to confer blessings.

Ushnishavijaya, Imperial workshop, Beijing, China, mid-18th c., gilt bronze with polychromy. Ushnishavijaya is the embodiment of a Buddhist mantra for protection that is supposed to extend life and bring about rebirth in Buddha Amitabha’s “Western Pure Land” Protective mantras consist of sacred syllables that encapsulate the spirit of Buddhist teaching. During a consecration ceremony the bronze was filled with relics such as written documents, medicinal herbs, or the remains of a teacher. These gave it the power to confer blessings.

Ritual dagger (Sanskrit: kila). Author not documented, Tibet (China) or Mongolia, 19th c., Copper, parcel-gilt. The stake-like dagger serves to conquer negative forces, subjugate demons, and eradicate obstacles on the road to enlightenment. Its pommel is shaped into the head of the tutelary god Hayagriva, whose attribute is the tiny horse’s head in his bristling hair. During the ritual, the tip of the dagger is thrust into the heart of a demon, symbolically nailing down its malign powers. This ritual is still practiced today.

Ritual dagger (Sanskrit: kila). Author not documented, Tibet (China) or Mongolia, 19th c., Copper, parcel-gilt. The stake-like dagger serves to conquer negative forces, subjugate demons, and eradicate obstacles on the road to enlightenment. Its pommel is shaped into the head of the tutelary god Hayagriva, whose attribute is the tiny horse’s head in his bristling hair. During the ritual, the tip of the dagger is thrust into the heart of a demon, symbolically nailing down its malign powers. This ritual is still practiced today.

Maniushri on his lion, Japan, c. 1800, wood with gilding, dry lacquer, and polychromy; glass. Bodhisattva Manjushri is revered as a mentor and teacher who helps believers in their quest for knowledge. Manjushri - which means the “graceful and venerable” - sits in a relaxed pose on his mount, the lion. Because he embodies the wisdom of Buddha, he holds a scroll in his left hand. The sword he originally held in his right hand, with which he symbolically slashes the fog of ignorance preventing enlightenment, has been lost.

Maniushri on his lion, Japan, c. 1800, wood with gilding, dry lacquer, and polychromy; glass. Bodhisattva Manjushri is revered as a mentor and teacher who helps believers in their quest for knowledge. Manjushri - which means the “graceful and venerable” - sits in a relaxed pose on his mount, the lion. Because he embodies the wisdom of Buddha, he holds a scroll in his left hand. The sword he originally held in his right hand, with which he symbolically slashes the fog of ignorance preventing enlightenment, has been lost.

Bodhisattva Mahasthamaprapta, Dolonor, Inner Mongolia (China), 19th c., gilt bronze with pigments, malachite, solid cast. The Bodhisattva Mahasthamaprapta is one of two figures accompanying the cosmic Buddha Amitabha. He represents the Buddha’s strength and wisdom. His attribute is the vase on his headdress. On his chest is the auspicious swastika emblem. The figure’s hands originally held a lotus blossom. Together with Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, he guides the dead to Buddha Amitabha’s “Western Pure Land”, a spiritual place of refuge that ends the sorrowful cycle of rebirth.

Bodhisattva Mahasthamaprapta, Dolonor, Inner Mongolia (China), 19th c., gilt bronze with pigments, malachite, solid cast. The Bodhisattva Mahasthamaprapta is one of two figures accompanying the cosmic Buddha Amitabha. He represents the Buddha’s strength and wisdom. His attribute is the vase on his headdress. On his chest is the auspicious swastika emblem. The figure’s hands originally held a lotus blossom. Together with Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, he guides the dead to Buddha Amitabha’s “Western Pure Land”, a spiritual place of refuge that ends the sorrowful cycle of rebirth.

Bodhisattva Kshitigarbha, Japan, c. 1850, wood with gilding, dry lacquer, and polychromy; metal. The Bodhisattva Kshitigarbha is depicted as a monk with shaven head. Supporting his head with his right hand, he sits in a relaxed pose on a lotus throne in a rocky landscape. His almost closed eyes indicate the deep meditation through which he liberates the dead from the hells and leads them to Buddha Amitabha’s “Western Pure Land”. Three flaming wish-fulfilling jewels adorn his radiant nimbus. The figure originally held a wish-fulfilling jewel and a pilgrim’s staff.

Bodhisattva Kshitigarbha, Japan, c. 1850, wood with gilding, dry lacquer, and polychromy; metal. The Bodhisattva Kshitigarbha is depicted as a monk with shaven head. Supporting his head with his right hand, he sits in a relaxed pose on a lotus throne in a rocky landscape. His almost closed eyes indicate the deep meditation through which he liberates the dead from the hells and leads them to Buddha Amitabha’s “Western Pure Land”. Three flaming wish-fulfilling jewels adorn his radiant nimbus. The figure originally held a wish-fulfilling jewel and a pilgrim’s staff.

Budai heshang, Shanxi, China, 17th c., cast iron with traces of gilt and engraved donor’s inscription. Budai heshang (Monk with hempen bag, c. 9th c.) is one of the most popular salvific figures of East Asia. Depicted with a big belly, wearing tattered clothing, and laughing, he is shown as a vagabond who lives from day to day and has no interest in studying sacred texts. In this way he challenges the ascetic ideal of the studious monk and shows that enlightenment and liberation from the cycle of rebirth are possible even without adhering to strict rules.

Budai heshang, Shanxi, China, 17th c., cast iron with traces of gilt and engraved donor’s inscription. Budai heshang (Monk with hempen bag, c. 9th c.) is one of the most popular salvific figures of East Asia. Depicted with a big belly, wearing tattered clothing, and laughing, he is shown as a vagabond who lives from day to day and has no interest in studying sacred texts. In this way he challenges the ascetic ideal of the studious monk and shows that enlightenment and liberation from the cycle of rebirth are possible even without adhering to strict rules.

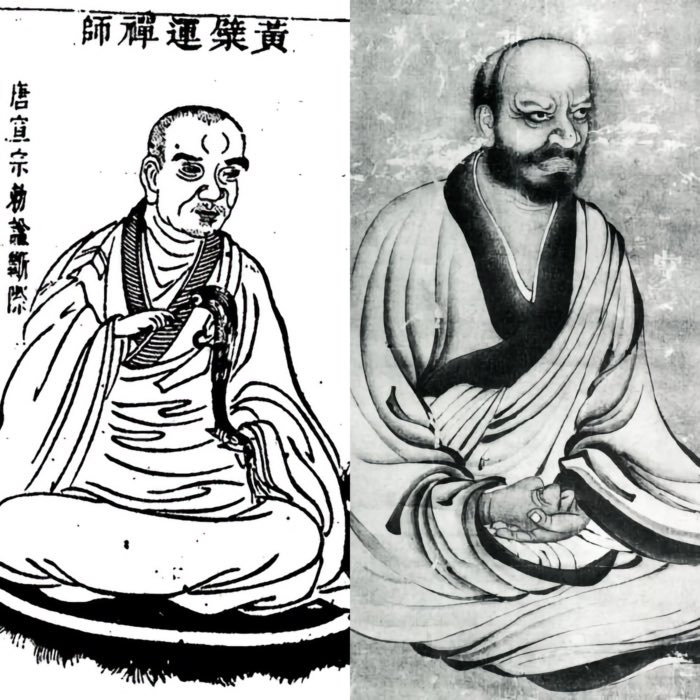

Arhats, China, Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), wood, lacquered and painted, with gold plating. Both wooden sculptures probably belonged to a larger group of figures of students of the Buddha. In China’s Chán Buddhist temples, special halls were dedicated to such groups. The relaxed sitting pose and the facial expression of the figures indicate that the monks were free of all social constraints. Thus monasticism is idealized as the path of liberation.

Arhats, China, Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), wood, lacquered and painted, with gold plating. Both wooden sculptures probably belonged to a larger group of figures of students of the Buddha. In China’s Chán Buddhist temples, special halls were dedicated to such groups. The relaxed sitting pose and the facial expression of the figures indicate that the monks were free of all social constraints. Thus monasticism is idealized as the path of liberation.

Buddha Bhaisajyaguru, China, Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), mid-15th century, bronze. The historical Buddha Shakyamuni is said to have taken the form of the medical Buddha Bhaisajyaguru towards the end of his life. He embodies the healing aspect of enlightenment that frees mankind from the suffering of rebirth. In his right hand he holds an Indian medicinal fruit. The spherical vessel in his left hand is said to contain a nectar that not only cures disease, but also provides long life and can even revive the dying.

Buddha Bhaisajyaguru, China, Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), mid-15th century, bronze. The historical Buddha Shakyamuni is said to have taken the form of the medical Buddha Bhaisajyaguru towards the end of his life. He embodies the healing aspect of enlightenment that frees mankind from the suffering of rebirth. In his right hand he holds an Indian medicinal fruit. The spherical vessel in his left hand is said to contain a nectar that not only cures disease, but also provides long life and can even revive the dying.

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, Jingdezhen, China, Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368), porcelain with Qingbai glaze. The Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara embodies the selfless benevolence of the Buddha. A gentle smile plays on his lips. His legs in the Lotus position point to the practice of meditation. The white glaze probably had a ritual function. A textbook on rituals from the Mongolian period (1279-1368) states that practitioners should imagine themselves as being as white as the moon in order to identify with Avalokiteshvara – and, as his embodiment, deliver the dead from the torments of hell.

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, Jingdezhen, China, Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368), porcelain with Qingbai glaze. The Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara embodies the selfless benevolence of the Buddha. A gentle smile plays on his lips. His legs in the Lotus position point to the practice of meditation. The white glaze probably had a ritual function. A textbook on rituals from the Mongolian period (1279-1368) states that practitioners should imagine themselves as being as white as the moon in order to identify with Avalokiteshvara – and, as his embodiment, deliver the dead from the torments of hell.

Buddha caves in Southeast Asia. With their incredible rock formations, secluded caves were considered magical places in many countries of Southeast Asia, even in the times before Buddhism. Hermit monks often retreated to such caves for meditation after the spread of Buddhism. These meditation caves subsequently attracted Buddhist believers who brought statues of the Buddha as votive offerings. In the so-called Buddha caves, fascinating collections of all kinds of images of the Buddha were created.

Buddha caves in Southeast Asia. With their incredible rock formations, secluded caves were considered magical places in many countries of Southeast Asia, even in the times before Buddhism. Hermit monks often retreated to such caves for meditation after the spread of Buddhism. These meditation caves subsequently attracted Buddhist believers who brought statues of the Buddha as votive offerings. In the so-called Buddha caves, fascinating collections of all kinds of images of the Buddha were created.

Collection of heads, Kizil Caves, Xinjiang, China.

Collection of heads, Kizil Caves, Xinjiang, China.

Bust of a Buddha, Thailand, 14th c., bronze, gilding remnants, U Thong School. When the Khmer withdrew from Central Thailand in the second half of the 14th century, the Thai U Thong style emerged. This style is named after the founder of the kingdom of Ayutthaya (founded in 1351). The oval face, small, pointed, snail-like curls, and the contour line around the hairline and lips are typical. Unfortunately, the flame flickering up from similar heads is missing.

Bust of a Buddha, Thailand, 14th c., bronze, gilding remnants, U Thong School. When the Khmer withdrew from Central Thailand in the second half of the 14th century, the Thai U Thong style emerged. This style is named after the founder of the kingdom of Ayutthaya (founded in 1351). The oval face, small, pointed, snail-like curls, and the contour line around the hairline and lips are typical. Unfortunately, the flame flickering up from similar heads is missing.

Sun- or Moonlight Bodhisattva, Northeast Thailand, Angkor Wat period, 1182-1186, sandstone. According to Khmer belief, the helpful Bodhisattvas “Sunlight” and “Moonlight” accompany the healing Buddha Bhaishajyaguru. With a medicine bottle in his hands, this sitting bodhisattva arguably once belonged to a trio: the medicine Buddha in the middle and a radiance bodhisattva on each side. Inscriptions from King Jayavarman II (see II 1420) praise this trinity.

Sun- or Moonlight Bodhisattva, Northeast Thailand, Angkor Wat period, 1182-1186, sandstone. According to Khmer belief, the helpful Bodhisattvas “Sunlight” and “Moonlight” accompany the healing Buddha Bhaishajyaguru. With a medicine bottle in his hands, this sitting bodhisattva arguably once belonged to a trio: the medicine Buddha in the middle and a radiance bodhisattva on each side. Inscriptions from King Jayavarman II (see II 1420) praise this trinity.

Buddha head, Cambodia, Angkor Thom, 14th - 16th c., sandstone, gilded. At the beginning of the 16th century, the kingdom of Ayutthaya (Thailand) wrested its supremacy from the Khmer Empire in Southeast Asia. This head of a Buddha in the late Avutthava style was found in the abandoned royal city of the Khmer, Angkor Thom. By the end of the 12th century, Angkor, which had previously been Hindu, became Buddhist.

Buddha head, Cambodia, Angkor Thom, 14th - 16th c., sandstone, gilded. At the beginning of the 16th century, the kingdom of Ayutthaya (Thailand) wrested its supremacy from the Khmer Empire in Southeast Asia. This head of a Buddha in the late Avutthava style was found in the abandoned royal city of the Khmer, Angkor Thom. By the end of the 12th century, Angkor, which had previously been Hindu, became Buddhist.

Four-armed Vishnu (center figure), Cambodia, 11th - 12th c., bronze, Angkor Wat style. This bronze in the Angkor Wat style depicts the Hindu god Vishnu: the god is (was) holding a flaming wheel (disc and sun symbol) in the upper right hand, a conch (in rituals used as a horn and holy water bowl) in the upper left hand, the remainders of a club in the lower left hand. In Khmer art, the round attribute in the lower right hand symbolizes the earth: Vishnu supports the earth.

Four-armed Vishnu (center figure), Cambodia, 11th - 12th c., bronze, Angkor Wat style. This bronze in the Angkor Wat style depicts the Hindu god Vishnu: the god is (was) holding a flaming wheel (disc and sun symbol) in the upper right hand, a conch (in rituals used as a horn and holy water bowl) in the upper left hand, the remainders of a club in the lower left hand. In Khmer art, the round attribute in the lower right hand symbolizes the earth: Vishnu supports the earth.

Eight-headed dancing Hevajra, Cambodia, 12th - 13th c., bronze. When King Jayavarman VII rebuilt the ruined Angkor in 1181 with a new Buddhist orientation, he made Hevajra a central deity. Above all, the rites of the secret cult around Hevajra were meant to empower the ruler to defeat both spiritual and real enemies. Here, Hevajra dances a dance of annihilation. Each of his eight heads has a third eye and in his 16 hands, he is holding figures and symbols in skull bowls.

Eight-headed dancing Hevajra, Cambodia, 12th - 13th c., bronze. When King Jayavarman VII rebuilt the ruined Angkor in 1181 with a new Buddhist orientation, he made Hevajra a central deity. Above all, the rites of the secret cult around Hevajra were meant to empower the ruler to defeat both spiritual and real enemies. Here, Hevajra dances a dance of annihilation. Each of his eight heads has a third eye and in his 16 hands, he is holding figures and symbols in skull bowls.

Scultpture from Buddhist caves, China.

Scultpture from Buddhist caves, China.

Padmasambhava (“Born from a lotus”), Mongolia, 18th / 19th c., painted bronze. The famous Tantric scholar is also called “Guru Rinpoche” (precious teacher).

Padmasambhava (“Born from a lotus”), Mongolia, 18th / 19th c., painted bronze. The famous Tantric scholar is also called “Guru Rinpoche” (precious teacher).

Vajrapani (“holder of the vajra”), China, Inner Mongolia, ca. 1700, fire-gilded copper. Vajrapani is an important protective and meditation deity. He is also known as the most important keeper and protector of secret writings. Here he appears in his wrathful form with flaming hair and wide-open mouth. His vajra (diamond sceptre) was originally in his right hand; his crown and long sash have also been lost.

Vajrapani (“holder of the vajra”), China, Inner Mongolia, ca. 1700, fire-gilded copper. Vajrapani is an important protective and meditation deity. He is also known as the most important keeper and protector of secret writings. Here he appears in his wrathful form with flaming hair and wide-open mouth. His vajra (diamond sceptre) was originally in his right hand; his crown and long sash have also been lost.

Eleven-headed Avalokiteshvara, Nepal, 18th c., bronze. This Avalokiteshvara is portrayed as standing with eight arms and ten heads. The lower nine heads have the same features, whereas the tenth head has a fierce appearance to defeat the opponents of Buddhism. The eleventh head right at the top is the head of the Buddha Amitabha, one of the five transcendent Buddhas (Jinas) and spiritual father of Avalokiteshvara.

Eleven-headed Avalokiteshvara, Nepal, 18th c., bronze. This Avalokiteshvara is portrayed as standing with eight arms and ten heads. The lower nine heads have the same features, whereas the tenth head has a fierce appearance to defeat the opponents of Buddhism. The eleventh head right at the top is the head of the Buddha Amitabha, one of the five transcendent Buddhas (Jinas) and spiritual father of Avalokiteshvara.

Buddhist shrine, Nepal, ca. 1800, gilded sheet bronze, precious stones. In private homes in Nepal it is common to erect a small house shrine for contemplation, in particular for the daily veneration of the family deity (kul devata). In the late 18th and early 19th century especially luxuriously decorated shrines were pro-duced. The cult image of this artistically worked shrine is the crowned Buddha Akshobhya made of rock crystal. The Buddha Amitabha is enthroned in the gable.

Buddhist shrine, Nepal, ca. 1800, gilded sheet bronze, precious stones. In private homes in Nepal it is common to erect a small house shrine for contemplation, in particular for the daily veneration of the family deity (kul devata). In the late 18th and early 19th century especially luxuriously decorated shrines were pro-duced. The cult image of this artistically worked shrine is the crowned Buddha Akshobhya made of rock crystal. The Buddha Amitabha is enthroned in the gable.

Vajrabhairava (Yamantaka), China, Tibet, 19th c., fire-gilded and painted copper. Vajrabhairava is the frightening, buffalo-headed form of the Bodhisattva Manjushri, whose peaceful head appears above on the head pyramid. The many arms indicate his great power. He vanquishes Yama, the lord of death. Vajrabhairava is an important meditation deity.

Vajrabhairava (Yamantaka), China, Tibet, 19th c., fire-gilded and painted copper. Vajrabhairava is the frightening, buffalo-headed form of the Bodhisattva Manjushri, whose peaceful head appears above on the head pyramid. The many arms indicate his great power. He vanquishes Yama, the lord of death. Vajrabhairava is an important meditation deity.

Lastly, there’s a sculpture on display which can aptly be described as “the many faces of Buddha”: The Miniature pagoda depicting the “Thousand Buddhas” from Northern Thailand, Chiang Mai, 16th century, bronze, gilded. This miniature pagoda may be understood as a distant Southeast Asian replica of the Mahabodhi Temple of Bodhgaya, India – the place where Buddha found enlightenment. Adorning the temple tower are countless small Buddhas in earth invoking gestures. The multiplication of the Buddhas here illustrates the idea that in Bodhgaya, not only the historical Buddha, but a thousand(s) Buddhas attained enlightenment.

Miniature pagoda depicting the Thousand Buddhas. See description in text above.

Miniature pagoda depicting the Thousand Buddhas. See description in text above.

comments