The first plastic depictions of Buddha’s life: Gandhara reliefs at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin

On my first visit to the Museum of Asian Art in the Humboldt Forum in Berlin this year, my attention was drawn to an arrangement of 15 stone reliefs. Upon closer inspection, I realized that they showed stages of the life of the historical Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama. What actually made the reliefs so special is the fact that they, made in Gandhara between the 1st and 3rd century, were one of the first narrative plastic representation of scenes of Buddha’s life. The very fact that these pieces originated from Gandhara gives them a pivotal role, as Buddhist art was previously more symbolic in nature such as the representation of stupas or Dharma wheels. Gandhara wasn’t just another region on the ancient map; it was a melting pot of civilizations, playing an indispensable part in shaping the visual language of Buddhism.

The Humboldt Forum in Berlin. The Museum of Asian Art is located on the 2nd floor.

The Humboldt Forum in Berlin. The Museum of Asian Art is located on the 2nd floor.

Gandhara and its role in the history of Buddhism

Gandhara, located in what is today northern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan, was a region of significant cultural and artistic exchange, particularly between the 1st and 3rd centuries. It sat at the crossroads of major trade routes, including the Silk Road, facilitating the flow of ideas, goods, and art between East and West.

Top: Kingdoms and cities of ancient Buddhism, with Gandhara located in the northwest of this region, during the time of the Buddha (c. 500 BCE). Source: Wikimediaꜛ. Bottom: Alexander’s empire at the time of its maximum expansion. Source: Wikimediaꜛ.

Top: Kingdoms and cities of ancient Buddhism, with Gandhara located in the northwest of this region, during the time of the Buddha (c. 500 BCE). Source: Wikimediaꜛ. Bottom: Alexander’s empire at the time of its maximum expansion. Source: Wikimediaꜛ.

One of the most impactful intersections was that of Hellenistic and Buddhist traditions. After the conquests of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE, Hellenistic influences began permeating the Indian subcontinent. The subsequent establishment of the Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdoms further solidified the fusion of these cultures. This unique blend is evident in Gandharan art (see also this post), where one can discern both the classical Greek forms and traditional Buddhist symbolism.

Adoration of a stupa, Central India, Sanchi, 1st c., sandstone, exhibited at the Humboldt Forum. A stupa is a mound housing Buddhist relics, which are hidden within its massive hill-shaped structure. An honorary umbrella crowns the monument. A stupa is worshipped by walking clockwise around it. Here, two men with turbans have put their hands together in the Indian gesture of worship. Heavenly beings bring flower offerings.

Adoration of a stupa, Central India, Sanchi, 1st c., sandstone, exhibited at the Humboldt Forum. A stupa is a mound housing Buddhist relics, which are hidden within its massive hill-shaped structure. An honorary umbrella crowns the monument. A stupa is worshipped by walking clockwise around it. Here, two men with turbans have put their hands together in the Indian gesture of worship. Heavenly beings bring flower offerings.

Adoration of the three jewels, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist. To become a Buddhist, one takes a three-fold refuge by speaking a solemn formula: “I take refuge in the Buddha, refuge in the doctrine, refuge in the monks’ community.” The trinity of the Buddha, doctrine and monks’ order is called the three jewels (triratna). Here they are symbolized by three wheels and worshipped by monks.

Adoration of the three jewels, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist. To become a Buddhist, one takes a three-fold refuge by speaking a solemn formula: “I take refuge in the Buddha, refuge in the doctrine, refuge in the monks’ community.” The trinity of the Buddha, doctrine and monks’ order is called the three jewels (triratna). Here they are symbolized by three wheels and worshipped by monks.

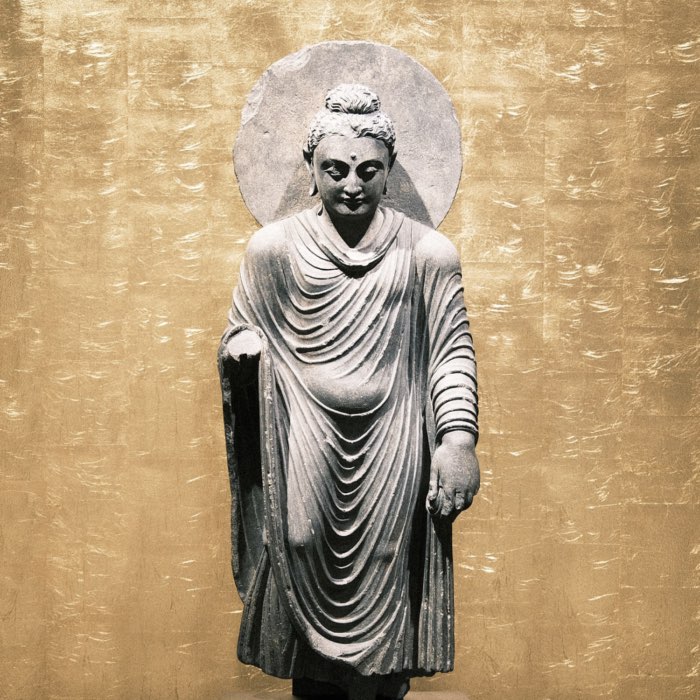

Central to the Gandharan artistic revolution was the anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha. Prior to this, the Buddha had typically been symbolized through aniconic symbols like the Bodhi tree, footprints, the Dharma wheel or stupas. The decision to represent the Buddha in human form was not merely artistic but deeply symbolic. It brought forth a tangible, relatable figure for devotees, making the teachings of Buddhism more accessible and visually engaging. The Gandharan reliefs, such as those presented in the Humboldt Forum, are testament to this pivotal shift. Through these intricate carvings, we witness the Buddha’s life events and teachings unfold in a sequential narrative, giving viewers a visual guide to his journey and enlightenment. In essence, the stone reliefs from Gandhara don’t merely depict stories; they represent a critical moment of cultural synthesis, where East met West, and where the spiritual was rendered in human form, bridging the gap between the ethereal and the tangible.

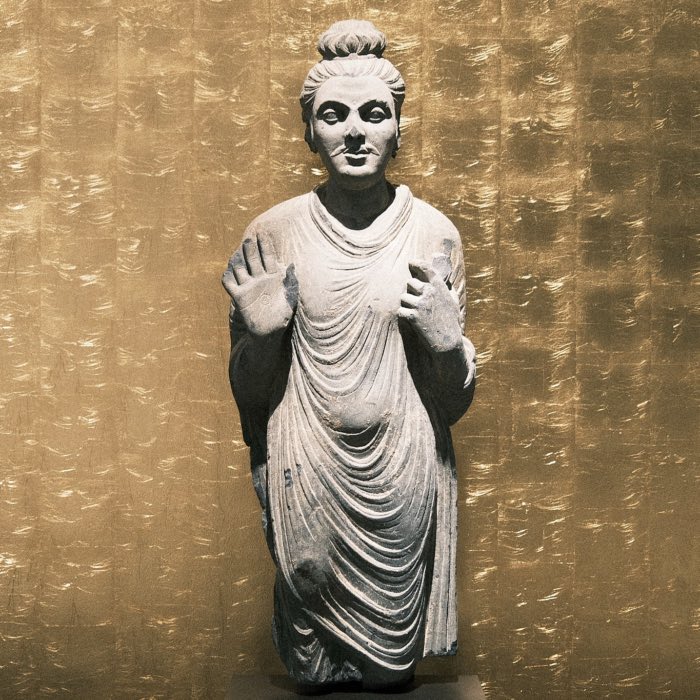

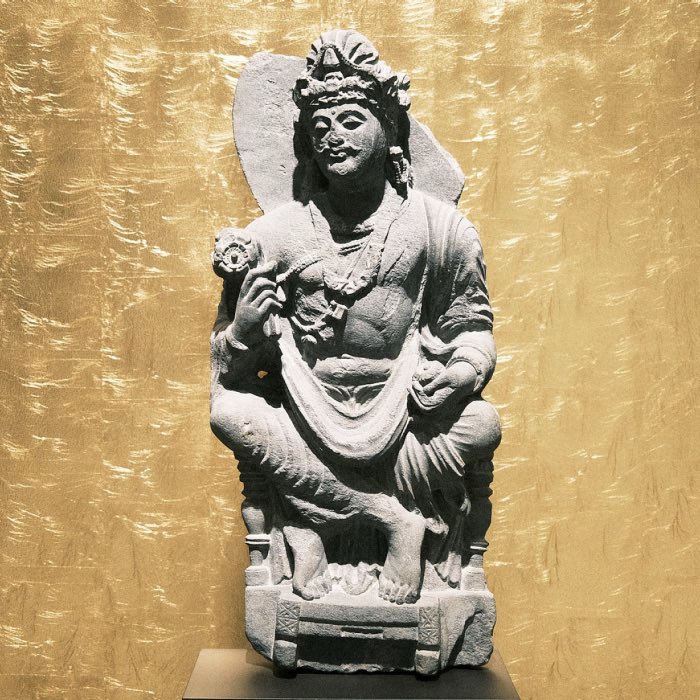

Left: The miracle-working Buddha, Afghanistan, Gandhara, 3rd c., schist, exhibited at the Humboldt Forum. An example of the fusion between Hellenistic and Buddhist art traditions. This anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha (Gandhara style) draws striking parallels with Hellenistic statues, notably in the finely chiseled tunic reminiscent of Greek sculptures. Background: In Shravasti, the Buddha performs the so-called twin miracle: first, the master rises into the air. From his shoulders flames ignite, from the hem of his monk’s robe water flows. Then he multiplies himself: We see other small Buddha figures next to his shoulders. With this imposing proof of his special abilities, he wins new followers. Right: For comparison: A Greek statue of a clothed man, seen in the Altes Museum, Berlin.

The 15 stone reliefs

I think what really shaped my impression of the 15 reliefs was how the Humboldt Forum arranged them. The reliefs were placed in chronological order on a circular wall structure. One thus had to walk around the installation to grasp all the reliefs as a coherent installation. Walking through it in this way, one not only experienced each of the depicted hagiographic stages of the Buddha’s life, but it also had almost a ritual and spiritual character, reminiscent of walking around Buddhist stupas. The placement of the relief ensured that each relief could be viewed separately. Through their chronological arrangement, as I walked around the installation, I was also reminded of another parallel: panels of the Passion of Christ that are usually mounted in Christian churches. With this parallel in mind, my impression of the reliefs became even stronger. Overall, the chosen installation allowed the experience of all 15 reliefs as a total work of art, which, at least for me, was a very impressive experience.

I don’t think that all the reliefs originally came from a single total work of art. Unfortunately, the Humboldt Forum did not provide any further information on this. However, the reliefs were accompanied by a short description of each scene, which I found very helpful in understanding the depicted events. The following 15 images show the reliefs in the order in which they were arranged, with the accompanying text from the Humboldt Forum.

The Buddha Dipankara prophesies the Buddhahood of Brahmin Sumedha. Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist. In India people believe in rebirth. Thus, also the historical Buddha Shakyamuni is said to have had many lives on his path to enlightenment. One day, as the Brahmin Sumedha, he met the Buddha Dipankara, who was the Enlightened One of his lifetime. When Sumedha threw himself to the ground before the Buddha Dipankara, he received the prophecy that he would one day become a Buddha.

The Buddha Dipankara prophesies the Buddhahood of Brahmin Sumedha. Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist. In India people believe in rebirth. Thus, also the historical Buddha Shakyamuni is said to have had many lives on his path to enlightenment. One day, as the Brahmin Sumedha, he met the Buddha Dipankara, who was the Enlightened One of his lifetime. When Sumedha threw himself to the ground before the Buddha Dipankara, he received the prophecy that he would one day become a Buddha.

The dream of Queen Maya and its interpretation. Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd - 3rd c., schist. Queen Maya has an intense dream one night in the palace of the Shakya king Shuddhodana (centre): a white elephant descends from heaven and enters her right hip. The next day, the king summons dream readers (left-hand scene). The dream readers prophesy the birth of an extraordinary child with a promising future to the ruling couple.

The dream of Queen Maya and its interpretation. Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd - 3rd c., schist. Queen Maya has an intense dream one night in the palace of the Shakya king Shuddhodana (centre): a white elephant descends from heaven and enters her right hip. The next day, the king summons dream readers (left-hand scene). The dream readers prophesy the birth of an extraordinary child with a promising future to the ruling couple.

The miraculous birth of the Buddha, Pakistan, Gandhara. 2nd - 3rd c., schist. The Buddha is born in the open. It is a painless, effortless birth: Queen Maya, the Buddha’s mother, is standing under a tree and grabbing a branch above her head. The baby emerges from her right hip. To the right are midwives. The gods Indra and Brahma approach from the left. They greet the newborn with reverence.

The miraculous birth of the Buddha, Pakistan, Gandhara. 2nd - 3rd c., schist. The Buddha is born in the open. It is a painless, effortless birth: Queen Maya, the Buddha’s mother, is standing under a tree and grabbing a branch above her head. The baby emerges from her right hip. To the right are midwives. The gods Indra and Brahma approach from the left. They greet the newborn with reverence.

The first bath and return home of the newborn. Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd - 3rd c., schist. After his birth, the Buddha immediately takes seven steps. He is then bathed by heavenly beings (right-hand scene). This image of the Buddha’s first bath is strikingly similar to Indian depictions of the consecration of a king: there too, the future king is doused with holy water from raised pitchers. (Left:) Mother and child are returning home on an elephant.

The first bath and return home of the newborn. Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd - 3rd c., schist. After his birth, the Buddha immediately takes seven steps. He is then bathed by heavenly beings (right-hand scene). This image of the Buddha’s first bath is strikingly similar to Indian depictions of the consecration of a king: there too, the future king is doused with holy water from raised pitchers. (Left:) Mother and child are returning home on an elephant.

The flight from the palace, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd - 3rd c., schist. As the king’s son, the Buddha spends his youth in his father’s palace. His carefree life ends with first encounters with illness, old age, and death. The young prince searches for spiritual stability. He no longer wants to become the king but rather a mendicant. (Centre:) He secretly leaves the palace at night, stealing off from the harem full of sleeping women. Celestial beings and a servant assist him.

The flight from the palace, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd - 3rd c., schist. As the king’s son, the Buddha spends his youth in his father’s palace. His carefree life ends with first encounters with illness, old age, and death. The young prince searches for spiritual stability. He no longer wants to become the king but rather a mendicant. (Centre:) He secretly leaves the palace at night, stealing off from the harem full of sleeping women. Celestial beings and a servant assist him.

Farewell to horse and servant, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist. In the wilderness, the fugitive prince removes his elegant clothes and jewelry. He hands them over to his long-time servant Chandaka. Now it is time to say goodbye: the horse Kanthaka kneels down for one last greeting, kissing the feet of its departing master. The servant and horse return to the palace. The Buddha begins his spiritual quest.

Farewell to horse and servant, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist. In the wilderness, the fugitive prince removes his elegant clothes and jewelry. He hands them over to his long-time servant Chandaka. Now it is time to say goodbye: the horse Kanthaka kneels down for one last greeting, kissing the feet of its departing master. The servant and horse return to the palace. The Buddha begins his spiritual quest.

The great fast and the finding of the Middle Way. Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist. In his quest the young Buddha follows several teachers. For six years, he practices the most severe asceticism, exposing himself to great austerities. Soon he is only skin and bones (right). But his effort brings no benediction. Then the Buddha breaks the fast: he bathes (centre) and eats again (left). He then develops the Middle Way with the help of mindfulness and meditation.

The great fast and the finding of the Middle Way. Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist. In his quest the young Buddha follows several teachers. For six years, he practices the most severe asceticism, exposing himself to great austerities. Soon he is only skin and bones (right). But his effort brings no benediction. Then the Buddha breaks the fast: he bathes (centre) and eats again (left). He then develops the Middle Way with the help of mindfulness and meditation.

Mara’s assault, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd - 3rd c., schist. The Buddha is sitting in meditation under the Tree of Enlightenment. He practices the quiet observation of the breath. Suddenly, wild figures besiege him. They embody noise, fear, aggression and passion. They are the troops of Mara, a symbolic figure in Buddhism for the entanglement in suffering. But Buddha preserves his equanimity. He frees himself from the power of Mara through meditation.

Mara’s assault, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd - 3rd c., schist. The Buddha is sitting in meditation under the Tree of Enlightenment. He practices the quiet observation of the breath. Suddenly, wild figures besiege him. They embody noise, fear, aggression and passion. They are the troops of Mara, a symbolic figure in Buddhism for the entanglement in suffering. But Buddha preserves his equanimity. He frees himself from the power of Mara through meditation.

The gods Indra and Brahma entreat the Buddha to deliver his first sermon, Pakistan, Gandhara, 1st c., schist. Glamorous self-representation does not correspond to the ideals of a Buddha. Thus, in the first few weeks after his enlightenment, the Enlightened One keeps his newly won wisdom to himself. But then heavenly beings come to the Buddha and ask several times for his insights to be proclaimed for the benefit of all living beings. Finally, the Buddha agrees.

The gods Indra and Brahma entreat the Buddha to deliver his first sermon, Pakistan, Gandhara, 1st c., schist. Glamorous self-representation does not correspond to the ideals of a Buddha. Thus, in the first few weeks after his enlightenment, the Enlightened One keeps his newly won wisdom to himself. But then heavenly beings come to the Buddha and ask several times for his insights to be proclaimed for the benefit of all living beings. Finally, the Buddha agrees.

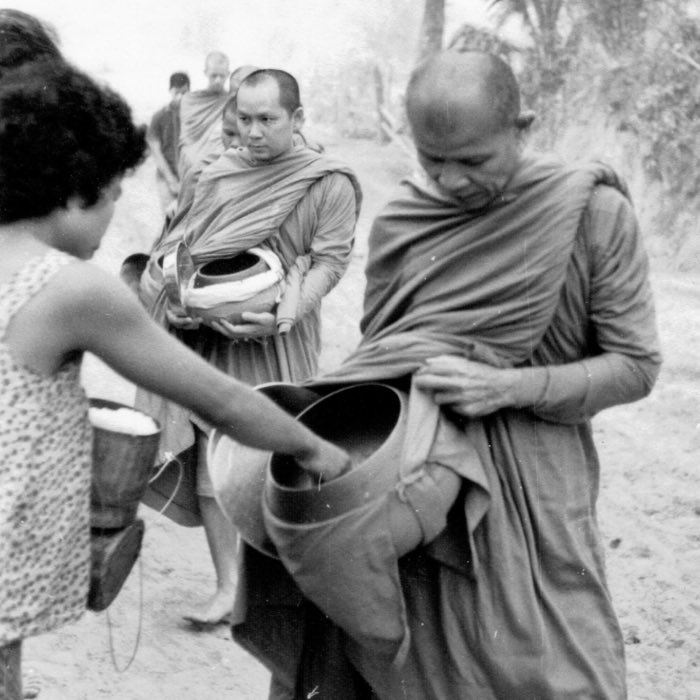

Buddha’s sermon to a group of monks, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist. The Buddha sits in the midst of a large crowd of (male) listeners. Some in the Buddha’s audience have put their hands together in the Indian gesture of worship (anjali mudra). There are seven Buddhist monks in the foreground. They can be recognized by their simple robes, bald, shaved heads, and the lack of any kind of jewelry.

Buddha’s sermon to a group of monks, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist. The Buddha sits in the midst of a large crowd of (male) listeners. Some in the Buddha’s audience have put their hands together in the Indian gesture of worship (anjali mudra). There are seven Buddhist monks in the foreground. They can be recognized by their simple robes, bald, shaved heads, and the lack of any kind of jewelry.

The Buddha as itinerant preacher, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd - 3rd c., schist. The Buddha and his monks arrive in a city (right). Townspeople respectfully welcome him. In the city (centre), the great teacher of wisdom, who is seated in a place of honour under a canopy, debates with elegantly dressed persons. Then the Buddha moves away (left). A drummer goes ahead of him.

The Buddha as itinerant preacher, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd - 3rd c., schist. The Buddha and his monks arrive in a city (right). Townspeople respectfully welcome him. In the city (centre), the great teacher of wisdom, who is seated in a place of honour under a canopy, debates with elegantly dressed persons. Then the Buddha moves away (left). A drummer goes ahead of him.

The passing away of the Buddha, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd-3rd c., schist. At the age of 80, the Buddha consumes a spoiled meal while traveling. Weakened, he lies down in a grove to die. He gives his monks encouragement one last time and gives instructions on how to deal with his mortal remains. Then the Buddha finally enters Nirvana. The relief depicts monks and laypeople gathering to mourn at the deathbed.

The passing away of the Buddha, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd-3rd c., schist. At the age of 80, the Buddha consumes a spoiled meal while traveling. Weakened, he lies down in a grove to die. He gives his monks encouragement one last time and gives instructions on how to deal with his mortal remains. Then the Buddha finally enters Nirvana. The relief depicts monks and laypeople gathering to mourn at the deathbed.

The cremation of the mortal remains of the Buddha, Pakistan, Gandhara, 1st-3rd c., schist. The Buddha’s corpse is to be cremated. But the mortal remains can only be ignited after one of the most important disciples of the Buddha, Mahakashyapa, who had arrived late, has honoured the feet of the deceased (right). Only then, the flames blaze up. Men pour oil onto the fire.

The cremation of the mortal remains of the Buddha, Pakistan, Gandhara, 1st-3rd c., schist. The Buddha’s corpse is to be cremated. But the mortal remains can only be ignited after one of the most important disciples of the Buddha, Mahakashyapa, who had arrived late, has honoured the feet of the deceased (right). Only then, the flames blaze up. Men pour oil onto the fire.

Distribution of the Buddha’s relics to eight monarchs, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist, News of the Buddha’s death spread rapidly. Several monarchs announce their interest in the relics. A quarrel arises. Finally, the Brahmin Drona divides the holy relics into eight equal parts and distributes them to the competitors. The relief shows Drona and the monarchs behind a table with eight relic-portions of equal size.

Distribution of the Buddha’s relics to eight monarchs, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist, News of the Buddha’s death spread rapidly. Several monarchs announce their interest in the relics. A quarrel arises. Finally, the Brahmin Drona divides the holy relics into eight equal parts and distributes them to the competitors. The relief shows Drona and the monarchs behind a table with eight relic-portions of equal size.

Worship of a stupa, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist. Buddhist relics are deposited in stupas, hill-grave-like monuments, with a small, hidden chamber inside. Umbrellas on top of the stupa indicate the venerability of the relics. One shows reverence for a stupa by walking clockwise around it. Here the stupa is set on a square pedestal with freestanding lion columns.

Worship of a stupa, Pakistan, Gandhara, 2nd -3rd c., schist. Buddhist relics are deposited in stupas, hill-grave-like monuments, with a small, hidden chamber inside. Umbrellas on top of the stupa indicate the venerability of the relics. One shows reverence for a stupa by walking clockwise around it. Here the stupa is set on a square pedestal with freestanding lion columns.

The next post ties directly into this one, showing more examples of Gandhara-style Buddhist sculpture.

Further readings

- Kurt Behrendt, How to Read Buddhist Art, 2019, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN: 978-1588396730

- David Jongeward, Buddhist Art of Gandhara: In the Ashmolean Museum, 2019, Ashmolean Museum, ISBN-13: 978-1910807224

- John Guy & Vincent Tournier, Tree and Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India, 2023, Book, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN: 9781588396938

comments