Don’t take isolated notes, connect them! Vannevar Bush on building a self-organizing network of knowledge

This is the first part of the series on personal knowledge management (PKM). Here, I will explain the theoretical background of my PKM implementation, that is based on building a network of knowledge by linking personal notes together. This concept is mainly based on the article As We May Think by Vannevar Bush, published in The Atlantic Monthly, July 19451.

Why taking personal notes? The problem of informational overflow

In today’s science world, we are exposed to an overwhelming flood of information of all sorts and from various sources. Even if we focus just on a small subset of that stream, that relates to our own research field only, it becomes very challenging to stay up-to-date due to the constant high number of new publications or due to the overall amount of available information. Even if we would find a perfect workflow for our informational researches and if we would also be able to not only collect, but also to read and process the information, another urgent problem would still remain: How should we handle all the valuable information within these sources? Overall, we are forced to think about solutions, tools and smart methods, to overcome this informational overflow.

Personal note-taking

One solution to address at least the latter problem is personal note-taking. Taking personal notes is not a recent invention by a smart start-up. Mankind is using it throughout all periods of history2. Writing something down may be our first and intuitive choice to process information when our brains are too overloaded to do the task ourselves. Personal notes help us to collect and sort input knowledge to better understand and draw conclusions from it. And they help us to make up our own ideas on a certain topic. Additionally, they provide the ability to come back to them at any time, to recall the information they contain, to continue our work with them, or to reuse them for new ideas.

However, to make use of our notes, they must be maintained in a smart and easy to use storage and managing system. In this part, we therefore focus on personal note-taking and available methods to establish such a smart note-taking, storage and access system.

Why does the organization of our notes matter?

Personal notes can be composed in many ways. We can handwrite them on a single sheet of paper or into a notebook, or we can write them digitally into a text file or into a note-taking app. Writing is a very useful tool and an important step to express our thoughts. However, we should not stop at this point and give up the opportunity to get more out of our notes. They contain highly valuable information, and we should go beyond the basic note-taking process and make our notes actually “work” for us. Fortunately, there is already a bunch of useful techniques and methods, that transform our notes into smart notes.

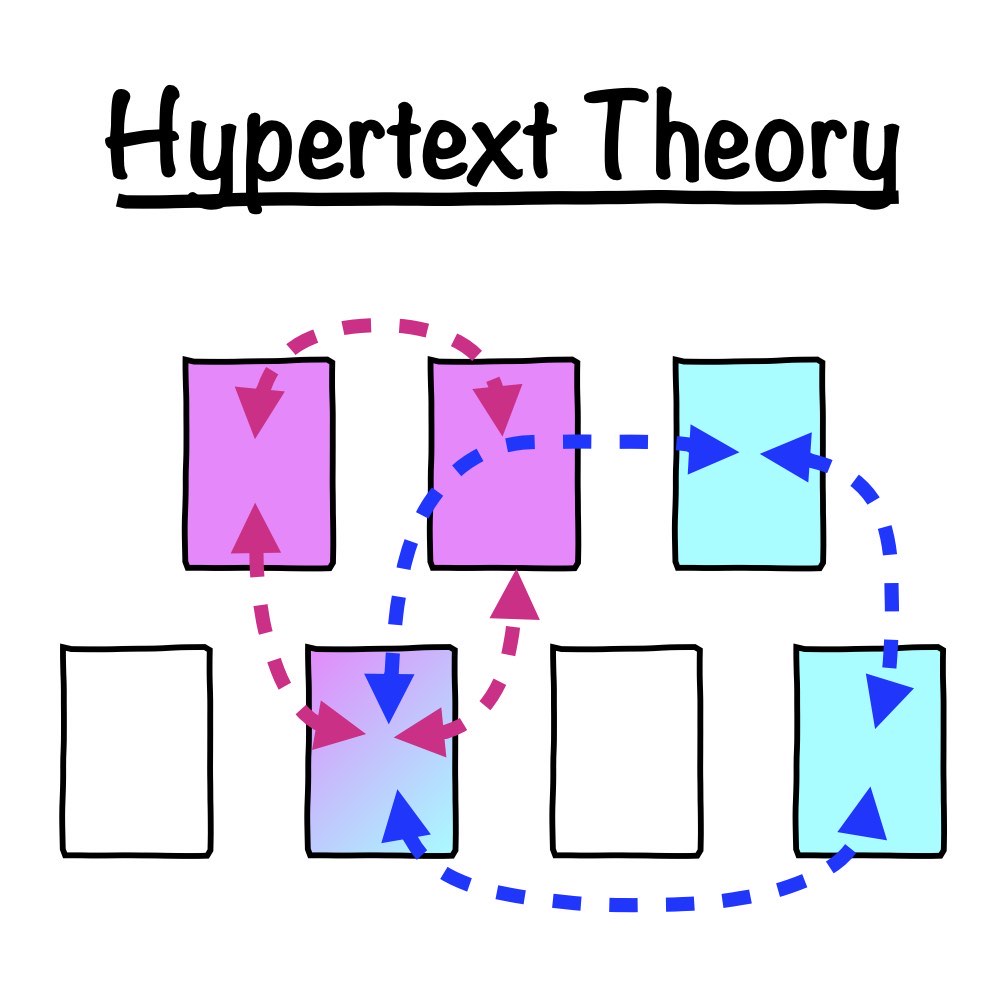

The Hypertext theory

The personal knowledge management system presented in this series is bases on what I’d like to call the “Hypertext theory”3. In the following paragraphs, we will learn that according to this theory, linking notes with each other (in a reasonable manner) will automatically form a self-organizing network of personal knowledge, that is not based on hierarchical structures. The last point is very important, because any system, no matter how intelligent and well-designed, will not work for us for a long time if it is not easy and fast to use – maintaining hierarchical structures is, however, a very time expensive job.

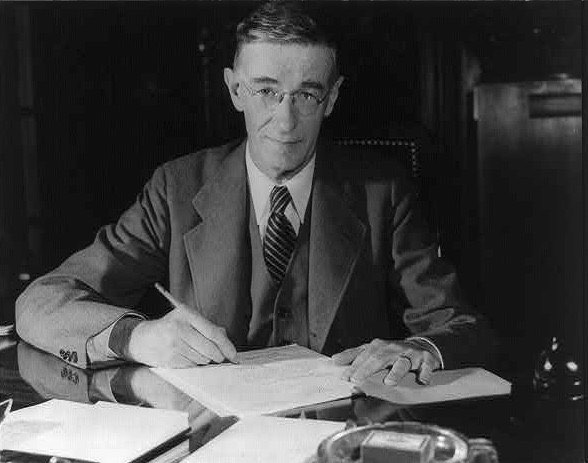

One of the first minds behind the Hypertext theory was Vannevar Bush. In the remaining part of this post, we focus on his ideas and review his article, that was published in The Atlantic Monthly in 19451.

As we may think

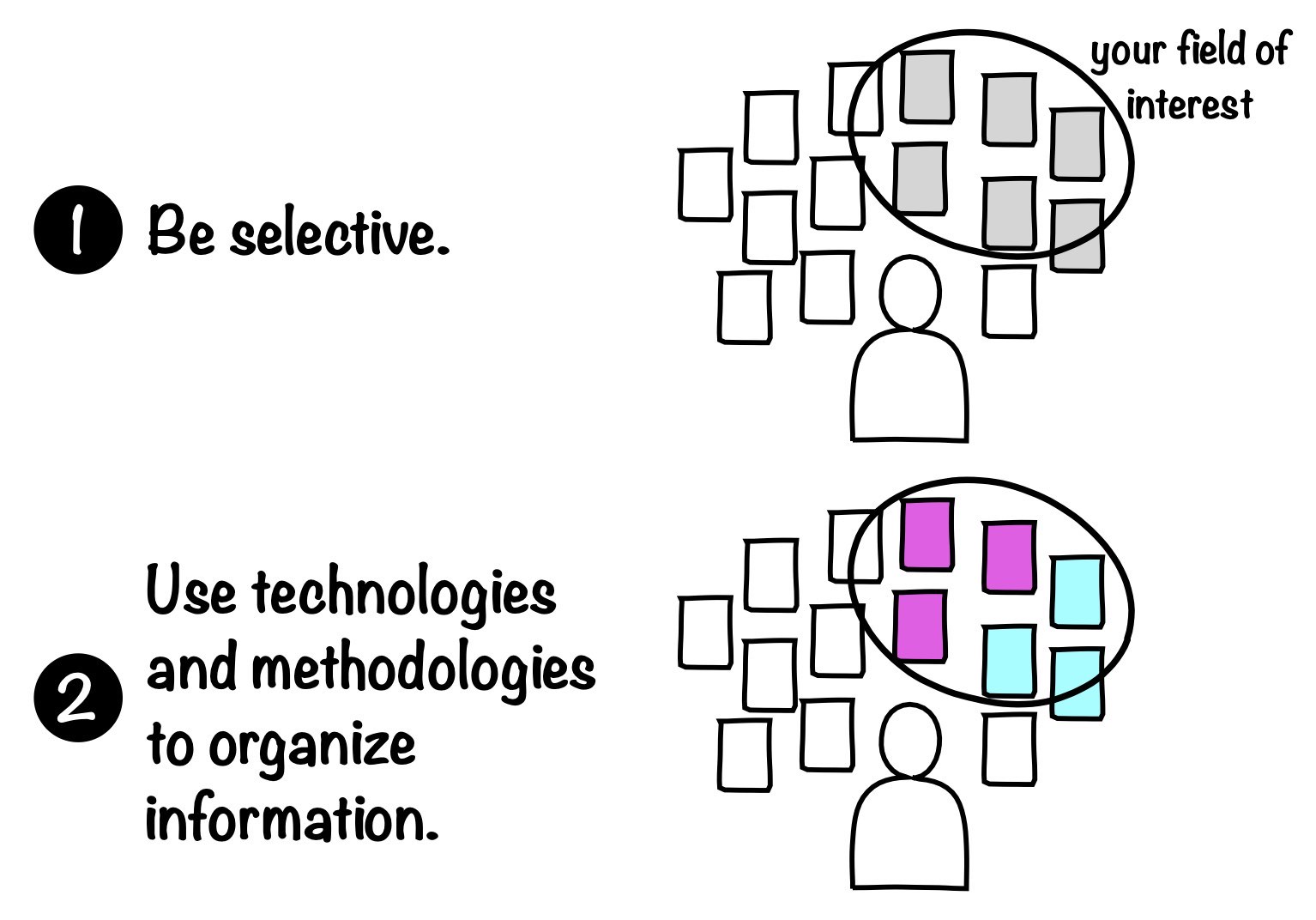

In 1945, Vannevar Bush, engineer and inventor, provided in his article As we may think two steps to solve the informational overflow. Even though decades are lying between us and Bush, and we now have much more and newer technological solutions available than at his time, it is his conceptual approach that is still valid today.

Bush’s first step addresses the high amount of incoming information and suggests to become more selective on the information that we gather:

Selection, in this broad sense, is a stone adze in the hands of a cabinetmaker.

– Vannevar Bush, As we may think

We should start focusing more on the valuable information that we can really benefit from, and valuable here means: What can further enrich our knowledge base? Put aside informational junk and don’t pay attention on it. A very simple and obvious approach, actually, but it’s worth expressing and consciously following.

Vannevar Bush 1944. License: public domain4.

Vannevar Bush 1944. License: public domain4.

Bush’s second step addresses the management of our knowledge. He argues, that the first part of knowledge management, collecting and sorting information, can actually be systematized and streamlined. He suggests to use technological aids, to which we hand over parts of the knowledge processing:

…there are plenty of mechanical aids with which to effect a transformation in scientific records.

– Vannevar Bush, As we may think

According to Bush, there are two ways to respond to the informational overflow: Being selective about the informational input, and making use of technology and methodology to organize information.

According to Bush, there are two ways to respond to the informational overflow: Being selective about the informational input, and making use of technology and methodology to organize information.

At the same time, Bush warns not to take the entire process of knowledge management as an arithmetic-mechanical procedure. Our own creativity should always be involved in this process. It should even become a central part of it. Technology should not replace creativity, but enable it by taking over as many time-consuming and repetitive steps as possible.

The problem of information retrieval

In addition to the technical management of the informational overflow, Bush has identified another problem that automatically occurs for large knowledge databases: The possibility to find the desired and relevant information in it.

Any note-taking system must include some sort of archiving system in which we can store the collected information. It is probably intuitive to store information in a hierarchical structure. A hierarchy, that is related to and reflects our current research. If we are researching historical events, we would sort the information chronologically. As physicists, we would rather file the notes by topic. In general, one could store all notes alphanumerically. The problem with hierarchical structures is, that they only make sense for the situation we were in at the time we researched the information. If the search premise changes, the previously rigidly defined hierarchical structure is probably no longer working for us. On the contrary, it is then more of a hindrance. Information is usually not only bound to a single category. Usually multiple associations are possible. In a rigid hierarchical structure, for any new topic I’d like to search, I have to know in advance, in which main and subsequent categories I have to look for. Without preliminary partial knowledge of the answer to the actual search query one is pretty stuck. This is neither flexible nor very efficient.

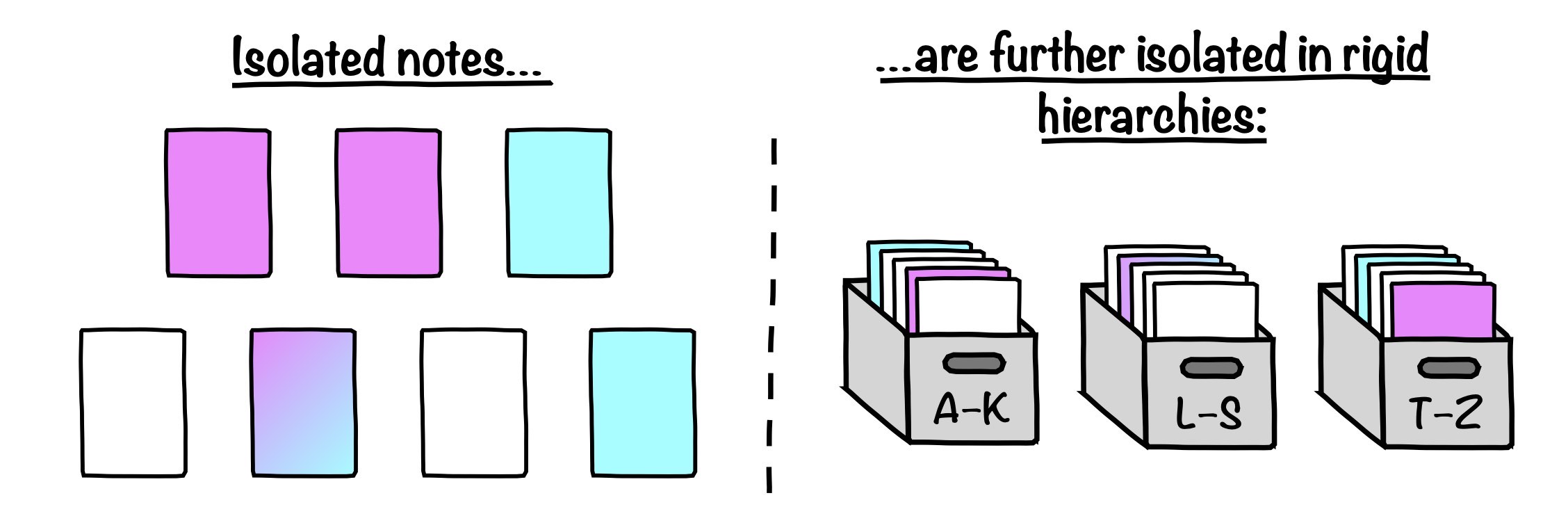

Isolated notes become even more isolated in rigid hierarchies: To find all relevant notes on a certain topic, one has to go through all existing categories. This problem could be solved with index cards. But even index cards follow hierarchies, and placed in another context, they quickly lose their advantage.

Isolated notes become even more isolated in rigid hierarchies: To find all relevant notes on a certain topic, one has to go through all existing categories. This problem could be solved with index cards. But even index cards follow hierarchies, and placed in another context, they quickly lose their advantage.

And there is also another problem with hierarchical structures: Once we have found the information we are looking for, maybe we remember another information related to this one. For the related information, we have to repeat the entire search as well as for any further related information. And: The association of one information with another is only based on our memory – or often on coincidence. Bush says, that our brain is actually not working like that:

The human mind does not work that way. It operates by association. With one item in its grasp, it snaps instantly to the next that is suggested by the association of thoughts, in accordance with some intricate web of trails carried by the cells of the brain…

– Vannevar Bush, As we may think

A system, that reflects the associative character of our thinking

Instead, our brain works according to Bush by making

Selection by association, rather than indexing …

– Vannevar Bush, As we may think

When we query information from our memory, we don’t scan “folder” by “folder”, jump from “drawer A” to “drawer Z”. We have an initial idea, a specific thought in mind, that we associate with further thoughts. We jump from this initial thought to further information, which in turn can become the source for other associations, and so on. In this way, we quickly get a broad overview of a certain topic, based on our previous knowledge – so far we can access and remember it.

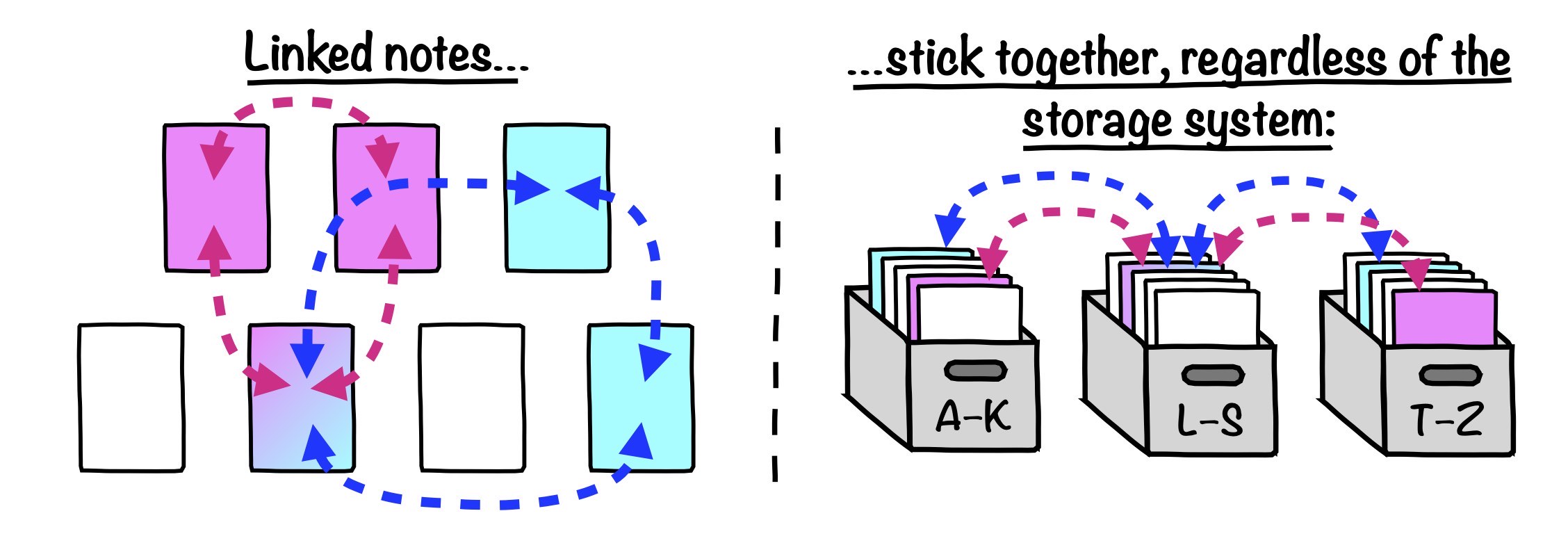

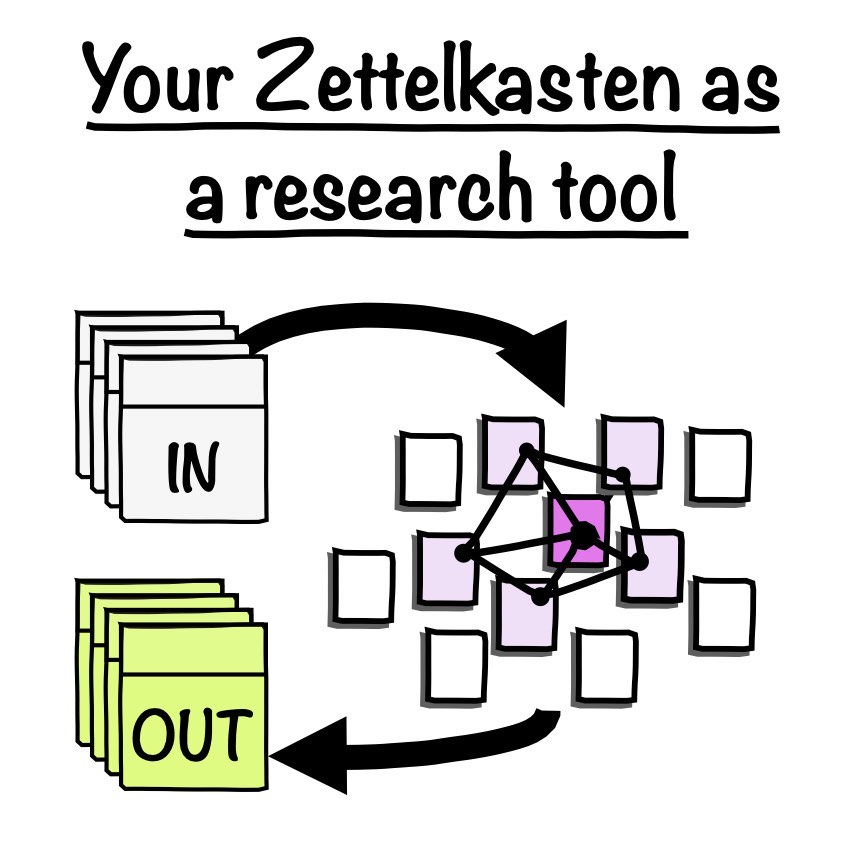

Linked notes mimic the associative character of memory retrieval. Even placed in a hierarchical storage system, the links preserve the relations between the notes and enable a fast and full information retrieval on a certain topic.

Linked notes mimic the associative character of memory retrieval. Even placed in a hierarchical storage system, the links preserve the relations between the notes and enable a fast and full information retrieval on a certain topic.

Therefore, instead of a hierarchically ordered storage for our information snippets, we need a system, that better reflects our associative way of thinking. Without giving it a specific a name, Bush provides the theoretical definition of such a system by requiring the following properties (in summary):

- technology-driven

- It should be a technology-based system to manage the informational overload, so that we can focus on the creative part in knowledge generation.

- flexible information in- and output interfaces

- It should enable the input of any amount of information from any source (books, papers, personal notes, photos, reports, newspaper articles, etc.) and store it with the capability of easy access.

- flexible editing

- It should offer flexible editing options for existing entries (e.g., for corrections or to add further information).

- linking information with each other

- It should be able to link information together (also multiple times).

- highlighting of relationships

- It should be able to highlight the relations between individual information units in order to quickly recognize links and patterns between them.

- flexible retrieval

- It should offer easy information retrieval and search, regardless of existing hierarchical structures (if any) or the type of information. Not explicitly stated by Bush, but this would also include the possibility to add and use keywords and other metadata.

- distraction-free content creation

- It should offer options for distraction- and obstacle-free creation of new content. This includes a proper presentation of the information found, to provide a broad overview of the searched topic (i.e., multitasking5).

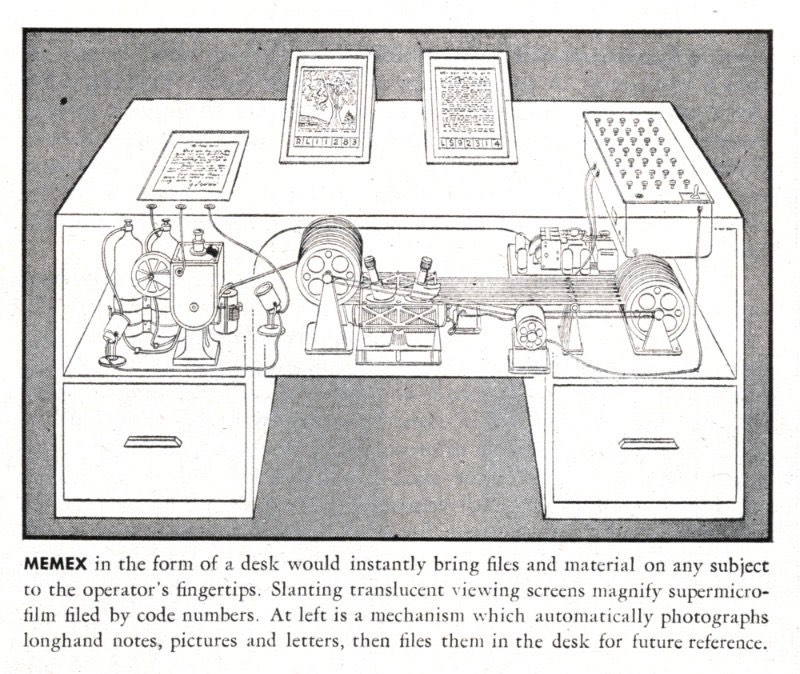

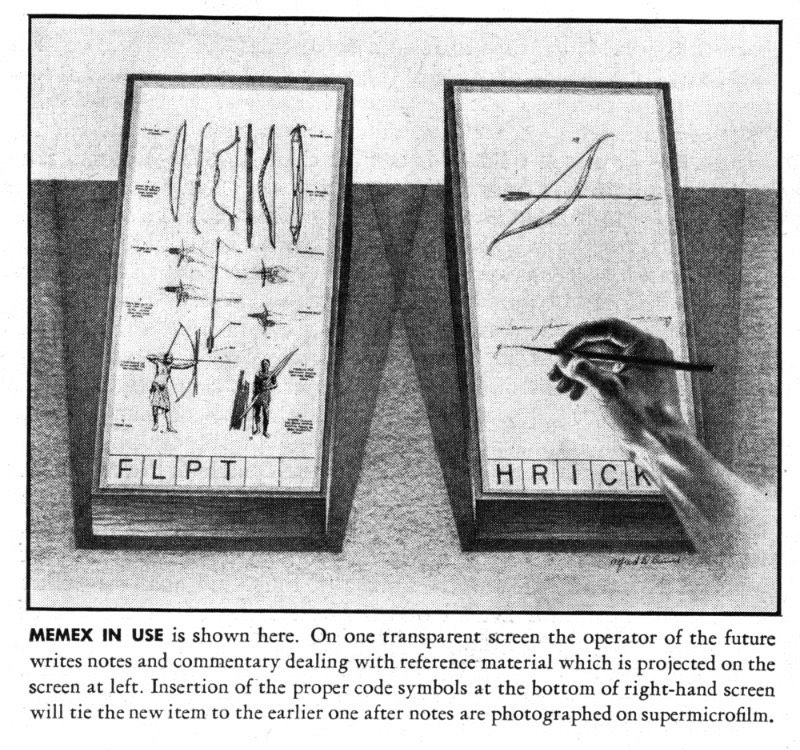

Bush also provided the description of a theoretical machine called “Memex”, that would meet all of his requirements. © Alfred D. Crimi, The Memex desk, from Life magazine 19 (11), p. 123-124.

Bush also provided the description of a theoretical machine called “Memex”, that would meet all of his requirements. © Alfred D. Crimi, The Memex desk, from Life magazine 19 (11), p. 123-124.

A network of personal knowledge

Probably the most important property of such a system is the possibility to link informational units (e.g., our notes) multiple times, just as our brain links information from different categories and different types, when it recognizes associations among them:

The process of tying two items together is the important thing … at any time, when one of these items is in view, the other can be instantly recalled merely…

– Vannevar Bush, As we may think

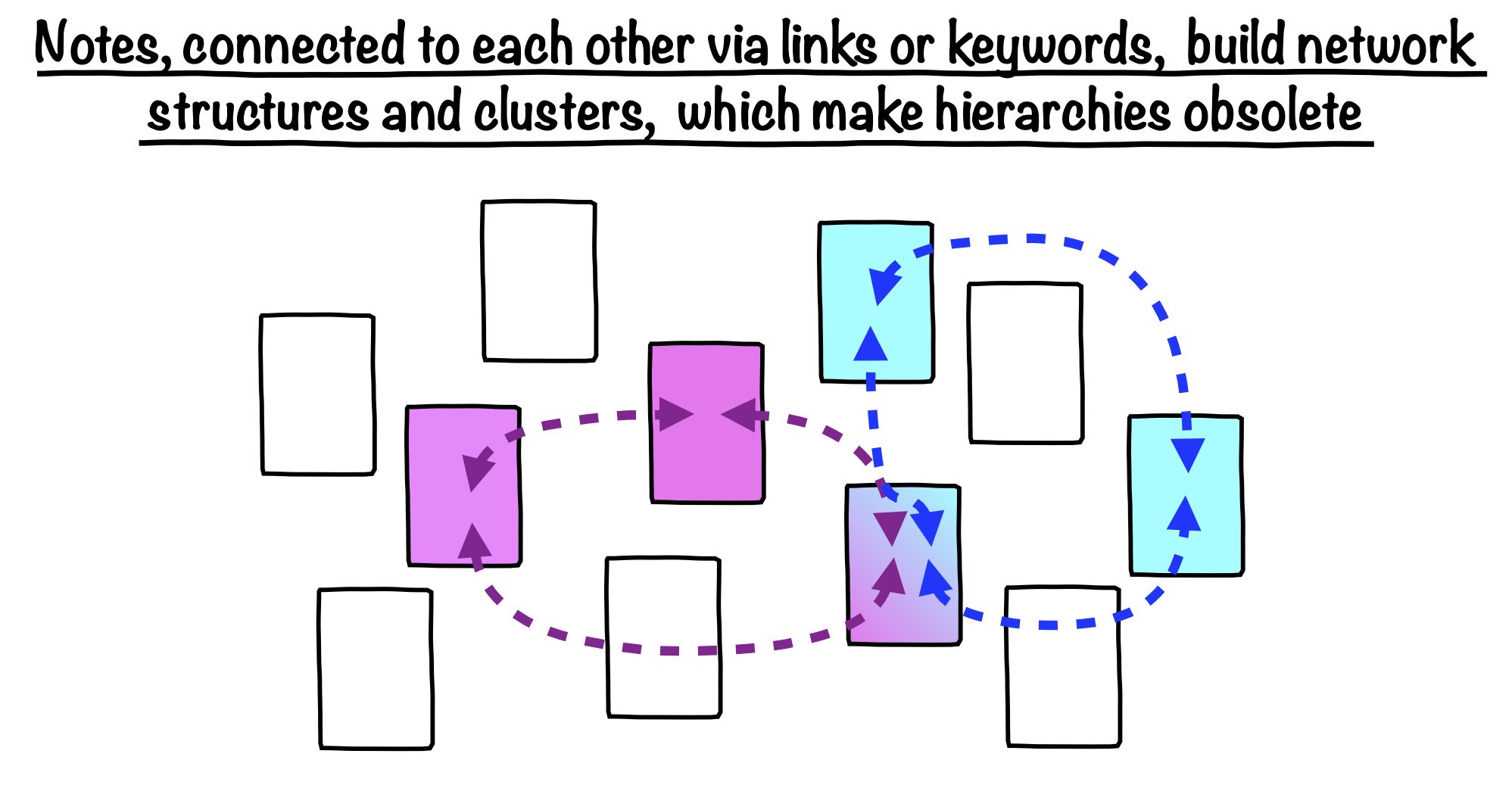

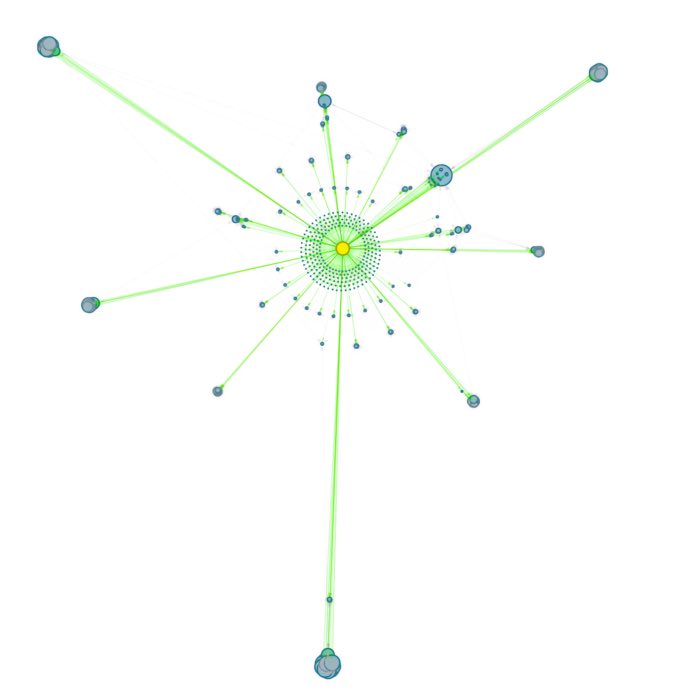

The linked notes in such a system would automatically form a network structure, a network of personal knowledge, that does not rely on any hierarchical ordering, and, hence, hierarchical structures become obsolete. Why? Niklas Luhmann, famous for his Zettelkasten method, that we will discuss in the second part of this series, provides6 a good explanation for this: Hierarchy-free networks have the property of being able to arrange themselves. The links and the typological keywords will automatically form flexible clusters, unpredictable, yet self-organizing:

As a result of extensive work with this technique a kind of secondary memory will arise, an alter ego with who we can constantly communicate. It proves to be similar to our own memory in that it does not have a thoroughly constructed order of its entirety, not hierarchy, and most certainly no linear structure like a book. …there will be preferred centers, formation of lumps and regions with which we will work more often than with others. …there will be incidental ideas which started as links from secondary passages and which are continuously enriched and expand so that they will tend increasingly to dominate system.

– Niklas Luhmann, Kommunikation mit Zettelkästen6

“Wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear”

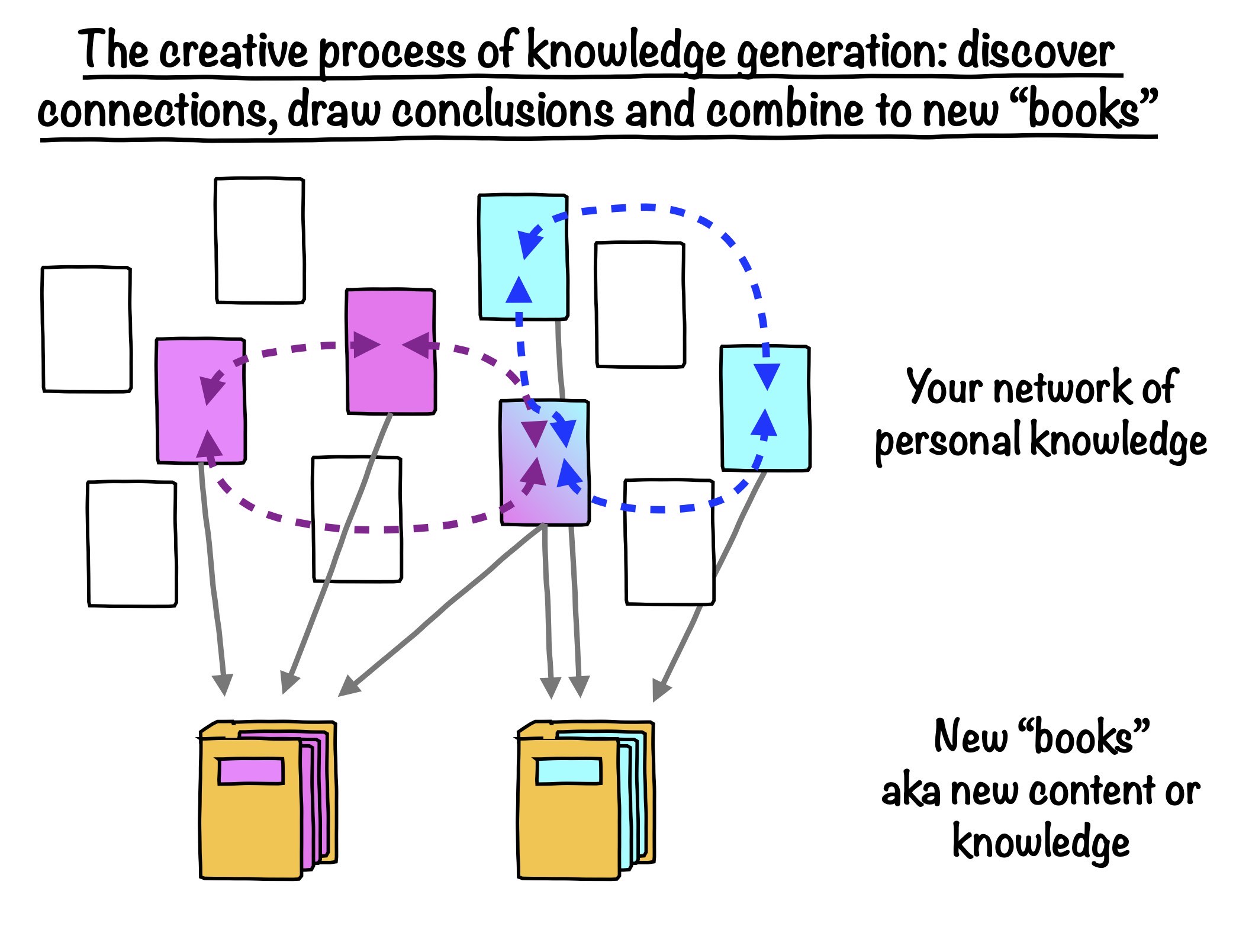

According to Bush, the multiple linking of information and the revelation of these links are the core of the creative process of generating new knowledge:

It is exactly as though the physical items had been gathered together from widely separated sources and bound together to form a new book.

– Vannevar Bush, As we may think

This “new book” is not rigid. We can compile it in any way we’d like to, depending on the results of our search and the related associations:

Wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready made with a mesh of associative trails running through them.

– Vannevar Bush, As we may think

And these “books” are more than just the sum of its parts. They are enriched by the conclusions we draw about the recognized patterns between these parts. This is where our creativity comes into play. From our network of knowledge, formed by individual, but linked bits of information, we generate new knowledge.

Your linked notes form a network of knowledge. And from this network of knowledge, you flexibly create wholly new “books” of content.

Your linked notes form a network of knowledge. And from this network of knowledge, you flexibly create wholly new “books” of content.

Organic growth

The smart thing about Bush’s idea is, that we can return to the information stored in our network at any time. We can create further “books” or expand and update existing information, no matter how much time has passed since we’ve created and stored it in our network. In this way, our network of knowledge grows organically and self-organized by the created connections.

And the ability to easily feed the network with selected information and add personal notes makes this a truly personal network of collected knowledge:

Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library.

– Vannevar Bush, As we may think

Hypertext after As we may think

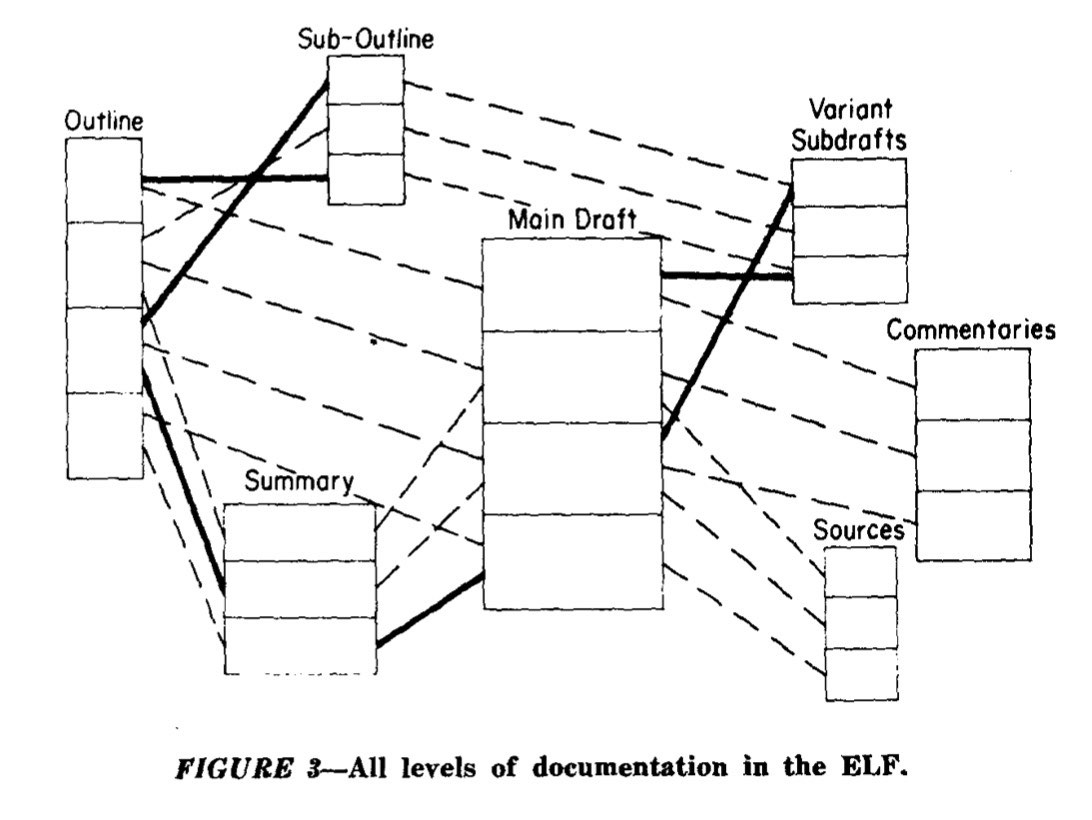

Bush’s foresight at his time is remarkable. Even though his article is about his Memex machine, Bush provides the first theoretical description of what will be called the concept of hypertext by the philosopher Ted Nelson in his work7 Complex information processing: a file structure for the complex, the changing and the indeterminate (1965), 20 years after Bush’s article:

Let me introduce the word “hypertext” to mean a body of written or pictorial material interconnected in such a complex way that it could not conveniently be presented or represented on paper.

– Ted Nelson, Complex information processing: a file structure for the complex, the changing and the indeterminate7

In 1965, Ted Nelson introduced the term hypertext in his work Complex information processing: A file structure for the complex, the changing and the indeterminate. Figure 3 of this work shows, how documents link with each other.

In 1965, Ted Nelson introduced the term hypertext in his work Complex information processing: A file structure for the complex, the changing and the indeterminate. Figure 3 of this work shows, how documents link with each other.

Another pioneer in this field is Douglas Engelbart, computer scientist and electrical engineer, who implemented with his NLS (oN-Line System) the first8 working hypertext system in 19689,10. Engelbart stated, that his work was inspired by Bush’s article11.

Keyboard terminal from an early NLS (oN-Line System) workstation, invented by Douglas Engelbart in the 1960s. The NLS was a visionary computer system, that focused on extending the collective work of knowledge workers. Among others, hypertext was one of the components of this system. Image source: DARPAꜛ.

Keyboard terminal from an early NLS (oN-Line System) workstation, invented by Douglas Engelbart in the 1960s. The NLS was a visionary computer system, that focused on extending the collective work of knowledge workers. Among others, hypertext was one of the components of this system. Image source: DARPAꜛ.

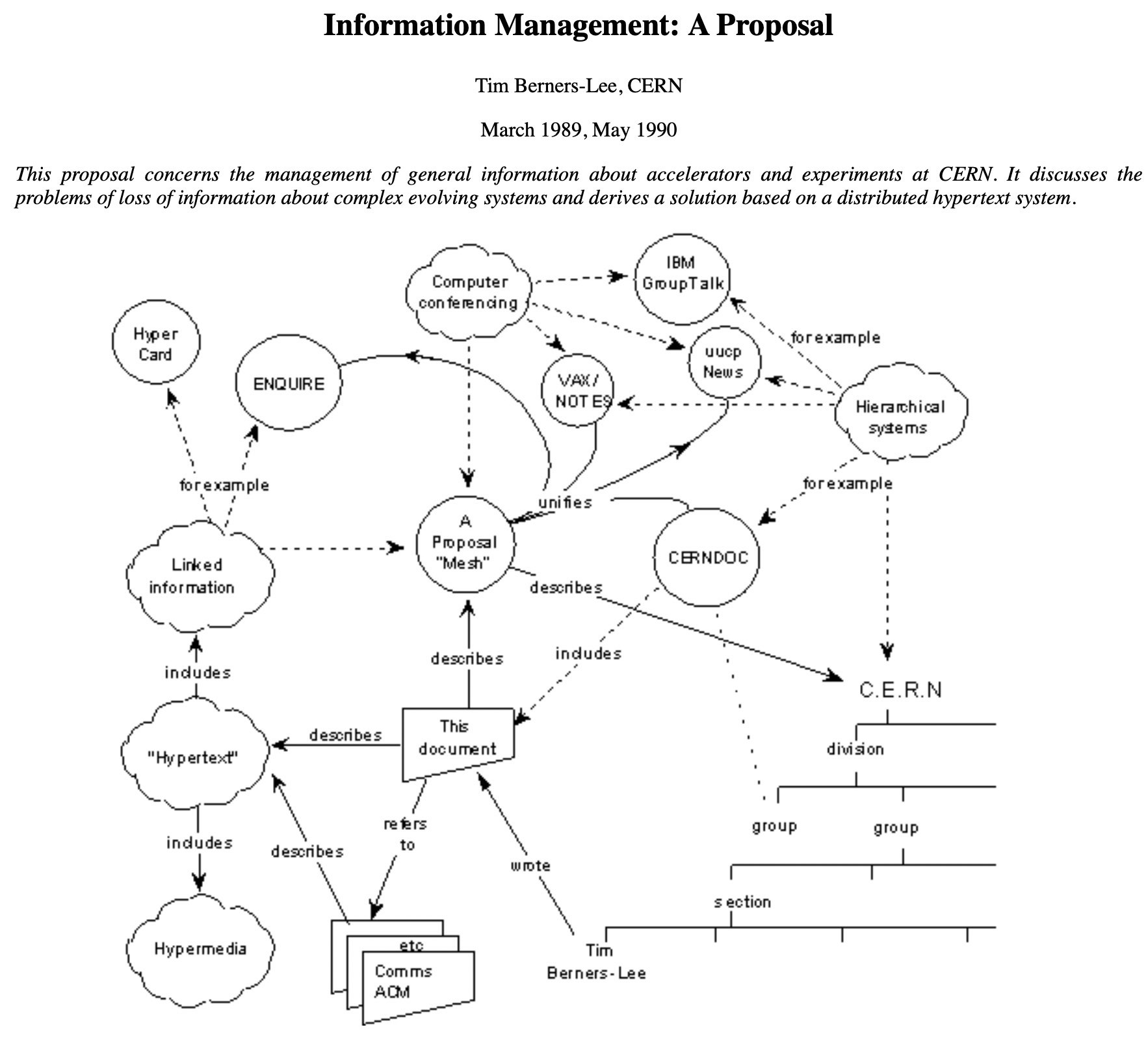

Finally, it was the physicist and computer scientist Sir Tim Berners-Lee, who, based on the hypertext concept, provided the basis of our today’s World Wide Web in his work “Information Management: A Proposal” (1989)12.

Tim Berners-Lee’s Information Management: A Proposal (1989). Screenshot taken from w3.org.ꜛ.

Tim Berners-Lee’s Information Management: A Proposal (1989). Screenshot taken from w3.org.ꜛ.

This is certainly a very shortened summary of the history of the hypertext. A somewhat more complete summary can be found hereꜛ13.

Conclusions

In his 1945 article As we may think, Vannevar Bush has drawn a way to overcome our today’s problem of informational overflow by becoming more selective and using technical and methodological solutions. He describes a theoretical system to manage knowledge, i.e., to organize, recall and make-use of our externally stored knowledge, in order to gain new insights on our so-far gathered knowledge and to generate new content from it. According to Bush’s concept, we would enrich such system with our personally selected information, our personal annotations on that information, and notes on our own ideas, which would make the system an explicitly personal one (a “private file and library” system). The technical and methodological key element of this system are the contextual links between the stored informational bits. These links will automatically establish a self-organizing network of personal knowledge, that grows organically with every new or edited information that we put in and with every new connection that is established between the informational bits. With his theoretical concept, Bush does not only provide a smart storage and retrieval solution for our externally stored knowledge. Bush’s concept is holistic and covers the process of personal knowledge management as a whole.

To realize his concept, Bush introduced the “Memex” machine. But it has so far remained only a theoretical concept, and we now still lack a practical implementation of Bush’s concept. In the next part we therefore discuss such a practical implementation by taking a closer look at the so-called “Zettelkasten method” by Niklas Luhmann.

References

-

Vannevar Bush, As We May Think, The Atlantic Monthly, 176, S. 101–108, July 1945, link ↩ ↩2

-

Sington, David, Vom Schreiben…, 2020, documentary streamed on ARTE in March 2022, link ↩

-

I did not invent this term. See, e.g. Schreiber, Chapter 2: Hypertext Theoryꜛ in English Literatures on the Internet, Masterarbeit, Universität Bayreuth, 1999. ↩

-

Vannevar Bush seated at a desk, between 1940 and 1944, License: public domain, retrieved from Wikipedia on April 20, 2022. linkꜛ ↩

-

“As he (the user) has several projection positions, he can leave one item in position while he calls up another.” – Vannevar Bush, As we may think1 ↩

-

Luhmann, Niklas, Kommunikation mit Zettelkästen. Ein Erfahrungsbericht. In: Niklas Luhmann: Universität als Milieu. Kleine Schriften. Hrsg. von André Kieserling. Haux, Bielefeld 1992, ISBN 3-925471-13-8, S. 53–61 (ursprünglich in: Horst Baier u.a. (Hrsg.): Öffentliche Meinung und sozialer Wandel. Für Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann. = Public opinion and social change. Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1981, ISBN 3-531-11533-2, S. 222–228.). Read the English translation hereꜛ. ↩ ↩2

-

Nelson, Theodor Holm, . Complex information processing: a file structure for the complex, the changing and the indeterminate, In: Proceedings of the 1965 20th national conference (ACM ‘65), 1965, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 84–100. doi: 10.1145/800197.806036 ↩ ↩2

-

Levene, Mark, and Wheeldon, Richard, Navigating the World-Wide-Web, 2004, DOI: 10.1007/978-3-662-10874-1_6, ↩

-

Engelbart, Douglas C., & English, William K. (1968). A research center for augmenting human intellect. Proceedings of the December 9-11, 1968, Fall Joint Computer Conference, Part I on - AFIPS ‘68 (Fall, Part I), 395. DOI: 10.1145/1476589.1476645 ↩

-

Engelbart, Douglas C., Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework, October 1962, linkꜛ ↩

-

Bardini, Thierry, Bootstrapping: Douglas Engelbart, Coevolution, and the Origins of Personal Computing, 2000, Stanford University Press, ISBN 10:0804738718 ↩

-

Berners-Lee, Tim, Information Management: A Proposal, CERN, March 1989, May 1990. linkꜛ ↩

-

Nielsen, Jakob, Chapter 3: The History of Hypertextꜛ, in: Multimedia And Hypertext, Elsevier Science, ISBN 10: 0125184085 ↩

comments